Tags

AI Industry, Consumer Sovereignty, Donald Trump, Favoritism, Foreign Direct Investment, Free trade, Noah Smith, Open Economy, Protectionism, Purchasing Power, rent seeking, Retaliatory Tariffs, Specialization, Tariffs

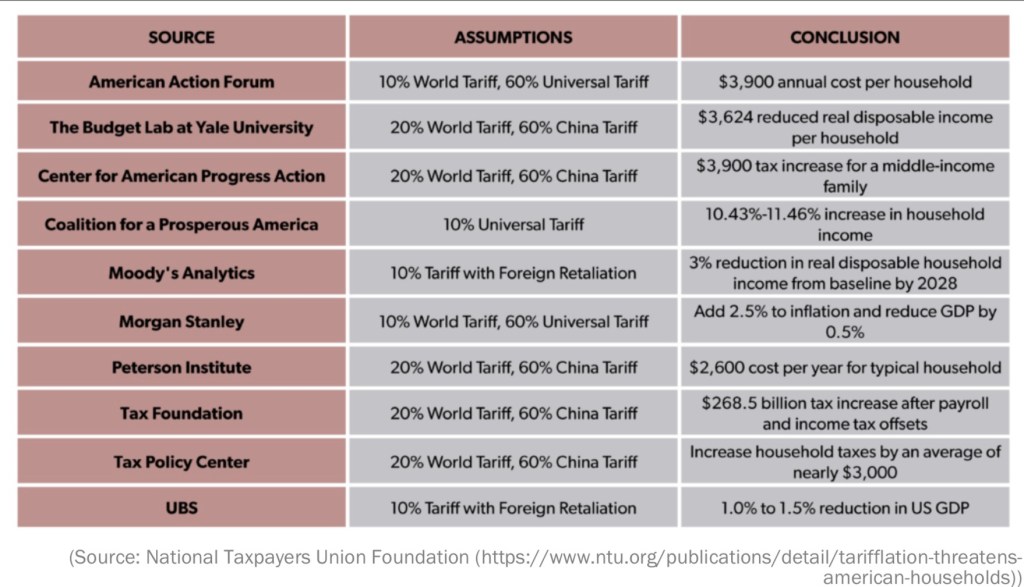

The table above is from Eric Boehm at Reason.com. It shows a variety of negative economic projections based on the likely imposition of tariffs by the incoming Trump Administration. Donald Trump’s protectionist agenda is motivated in large part by the notion that imports of foreign goods and services harm the U.S. economy. This misapprehension is common on both the populist left and the nationalist right, but it is also fueled by special interests averse to competition. Especially puzzling are those who extol the virtues of capitalism and free markets while claiming that free markets across borders are inimical to our nation’s economic interests.

Imports and Domestic Spending

Many assume that imports directly reduce GDP. In fact, on this point, some might be led astray by a superficial exposure to macroeconomics. As Noah Smith has noted, they might think back to the simple spending definition of GDP they learned as college freshmen:

GDP = C + I + G + (X – M),

where C is consumer spending on final goods and services, I is investment spending, G is government spending, X is foreign spending on U.S. exports, and M is U.S. spending on imports from abroad. So imports are subtracted! Doesn’t that mean imports directly reduce GDP?

The key here is to recognize that C, I, and G already include spending on imported goods. Therefore, imports must be subtracted from the spending totals to find the value spent on domestically-produced final goods and services. No, imports are not a direct, net subtraction from GDP.

Your Loathsome Foreign Car

Of course the domestic impact of imports goes deeper than this simple accounting framework. If someone decides to purchase an imported good instead of a close substitute produced domestically, what happens to GDP? If the decision has an immediate impact on production, then U.S. GDP declines. Otherwise, the domestic good is new inventory investment (part of I above), and there is no change. But if the import decision is repeated, the result is permanently lower U.S. GDP relative to the alternative, as producers won’t want to add to inventories indefinitely. The same is true if a domestic producer decides to purchase a component or raw material produced overseas rather than one produced at home.

The import decision causes a domestic producer to lose a sale along with the profit that sale would have earned. That puts pressure on the firm’s workers and wages as well. The firm still has the value of the unit in inventory, but if the import decision is repeated there will be more substantial follow-on effects on production, employment, spending, and saving.

Not So Fast

There is still more to the story, of course. By purchasing the foreign good,,which in the buyer’s estimation delivers greater value at that point in time, there is a gain in consumer surplus that is very real. To the buyer, that gain is perhaps equivalent to dollars in the bank. Their real wealth has increased relative to the surplus value of the foregone domestic purchase. This, too, will likely have follow-on effects in terms of spending and saving, but positive effects.

Therefore, to a first approximation, the immediate effects of an import purchase on total domestic welfare are ambiguous. Consumers of imports gain value; producers of import-competing goods lose value.

As to the loss of the domestic sale, competition is tough, but it greatly contributes to the efficiency of the free market system and to the well being of consumers. Let’s face it: ultimately, the whole point of economic activity is to enable consumption. Production has no other purpose. So producers must react to competition and strive to improve value for buyers along any margins they can. That, in turn, is unequivocally positive for potential buyers both here and abroad.

It’s also true that the purchase of foreign goods means that dollars must be sold in exchange for foreign currency. That weakens the dollar, but those “excess dollars” are generally used to purchase U.S. assets, including physical capital. That direct investment promotes economic growth.

Open Economy, Open Mind

No matter what you believe about the net benefits or costs of a single import transaction like the one described above, it is misleading to draw conclusions about the benefits of foreign trade based on a single transaction, or even a series of repeated transactions.

First, consumer sovereignty is based on freedom of choice, including the freedom to purchase from any seller, domestic or foreign. Consumers greatly benefit from that broad freedom. Add to that the benefit of producers who are free to purchase inputs from any source they believe to offer the greatest value (a benefit that ultimately flows through to consumers). These freedoms ultimately enhance productivity and well being.

Trade across borders leverages the same economic advantages as trade within borders. People tend to accept the latter as truth without giving it a thought, yet the former is often rejected reflexively. The question is inappropriately bound up in issues like patriotism and, over time, an excessive focus on high-visibility job losses in traditional industries.

Trade allows people and their countries to specialize in producing things at which they are comparatively efficient, i.e., in which they are lower-cost producers. This is at the very heart of mutually beneficial exchange: no party to a voluntary transaction expects to suffer a loss. And in trade, when an external, domestic party sustains a lost sale, for example, they have the opportunity to improve or reallocate their resources to endeavors to which they are better suited. So there are direct gains from trade and there are indirect gains via the discipline of competition, including the benefits of reallocating scarce resources from inefficient to efficient uses.

Tariff Gains

Now we shift gears to tariffs: interventions having benefits that are more concentrated than costs, and which tend to be more ephemeral:

— Domestic producers who compete with imports gain through the grant of additional market power, given the tax on foreign goods and services. These producers now have more pricing flexibility, and what is often more pertinent, survivability.

— Workers at domestic firms will benefit to the extent that their employers face reduced foreign competition. Some combination of employment, hours, and wages may rise.

— Some firms have mixed gains and losses, with more pricing power over final product but elevated costs due to the use of taxed foreign components.

Tariff Losses

Who pays when government succumbs to irrational protectionist pressure and attempts to restrict imports via tariffs?

— Domestic consumers suffer a loss of freedom and bear a large part of the burden of the tariff tax.

— Higher prices for imports lead to higher prices for competing domestic goods, causing consumers to experience a loss of purchasing power.

— Domestic businesses suffer a loss of control over input decisions. Those already utilizing foreign inputs (and their buyers downstream) bear some of the burden of the tariff tax. For example, tariffs could be quite damaging to the U.S. AI industry, a result that would run strongly contrary to Trump’s promise to promote American AI.

— The U.S. suffers a loss of foreign investment, which could engender higher interest rates, lower productivity growth, and lower real wages.

— As Tyler Cowen puts it in a review of this paper, “… lobbying, logrolling and political horse-trading were essential features of the shift toward higher US tariffs. A lot of the tariffs of the time [1870 -1909] depended on which party controlled Congress, rather than economic rationality.“

— Tariffs tend to reduce economic growth due to diminished productivity in tariff-protected industries, which also erodes real wages. Less productive firms capture a significant share of the benefits of tariffs, so that economic growth falls due to a compositional effect. Higher prices for imports and import-competing goods undermine the real gains of import-protected workers.

— Finally, tariffs invariably beget retaliatory tariffs by erstwhile friendly trading partners. Export industries and their employees take a direct hit. This retaliation damages the prospects of the most productive exporters, while weaker exporting firms might be forced to close shop unnecessarily.

One other note: the discussion of gains and losses above is essentially the same for policies that reward the use of American labor via tax breaks. This not only penalizes imports of final and intermediate foreign goods, it subsidizes high-cost domestic labor. Obviously, the upshot is a less competitive U.S. economy.

Tariff-Threat Policy

To be fair, Donald Trump has said he’d use the threat of tariffs strategically to achieve a variety of objectives, not all of which are directly related to trade. We can hope that many of those threats won’t be acted upon. On one hand, that’s more appealing than general tariffs, with potential foreign policy gains and less in the way of general damage to the economy. On the other hand, the discretionary application of tariffs could invite political favoritism and foster a corrupt rent-seeking environment.

Conclusion

Trade protectionism protects weak and strong producers alike. The weak should not be given artificial incentives to produce goods inefficiently. That’s simply a waste of resources. Protecting the strong is unnecessary and discourages the drive for efficiency as well as real value creation. It lends market power to already powerful firms, leading to higher prices and penalizing domestic consumers.

One last aside: tariffs cannot raise anywhere close to the revenue necessary to replace the income tax, an absurd claim made by Trump on the campaign trail.

Only free trade is consistent with the values of a free society. It enhances choice, makes markets more competitive, creates incentives for efficiency, and cultivates opportunities for economic growth, That would serve Trump and the nation much better than the fixation on tariffs.

Pingback: The Tariff Games | Sacred Cow Chips