Tags

Bank of Japan, Donald Trump, European Central Bank, Federal Reserve, Fiscal policy, Inflation, Interest Rates, Investor Expectations, Real Interest Rates, Swiss National Bank, Treasury Debt, Zohran Mamdani

Donald Trump’s latest volley against the Federal Reserve accuses the central bank of fixing interest rates at artificially high levels compared to rates in other developed countries. He repeatedly demands that the Fed make a large cut to its federal funds rate target, in the apparent belief that other rates will immediately fall with it. While a highly imperfect analogy, that’s a bit like saying that long-term parking in New York City would be cheaper if only hourly rates were cut to what’s charged in Omaha, and with only favorable consequences. Don’t tell Mamdani!

Trump believes the Fed’s restrictive monetary policy is preventing the economy from achieving its potential under his policies. He also argues that the Fed’s “high-rate” policy is costing the federal government and taxpayers hundreds of billions in excessive interest on federal debt. High rates can certainly impede growth and raise the cost of debt service. The question is whether there is a policy that can facilitate growth and reduce borrowing costs without risking other objectives, most notably price stability.

Delusions of Control

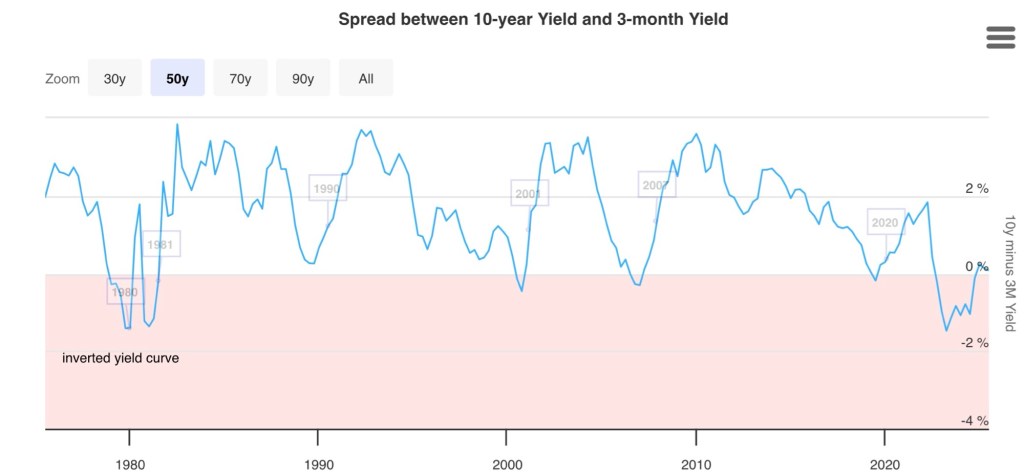

The financial community understands that the Fed does not directly control rates paid by the Treasury on federal debt. The Fed has its most influence on rates at the short end of the maturity spectrum. Rates on longer-term Treasury notes and bonds are subject to a variety of market forces, including expected inflation, the expected future path of federal deficits, and the perceived direction of the economy, to name a few. The Fed simply cannot dictate investor sentiments and expectations, and the ongoing flood of new Treasury debt complicates matters.

Another fundamental lesson for Trump is that cross-country comparisons of interest rates are meaningless outside the context of differing economic conditions. Market interest rates are driven by things that vary from one country to another, such as expected inflation rates, economic policies, currency values, and the strength of the home economy. Differences in rates are always the result of combinations of circumstances and expectations, which can be highly varied.

A Few Comparisons

A few examples will help reinforce this point. Below, I compare the U.S. to a few other countries in terms of recent short-term central bank rate targets and long-term market interest rates. Then we can ask what conditions explain these divergencies. For reference, the current fed funds rate target range is 4.25 – 4.5%, while 10-year Treasury bonds have traded recently at yields in the same range. Current U.S. inflation is roughly 2.5%.

It’s important to remember that markets attempt to price bonds to compensate buyers for expected future inflation. Currently, the 10-year “breakeven” inflation implied by indexed Treasury bonds is about 2.35% (but it is closer to 3% at short durations). That means unindexed Treasury bonds yielding 4.4% offer an expected real yield just above 2%. Accounting for expected inflation often narrows the gap between U.S. interest rates and foreign rates, but not always.

Switzerland: The Swiss National Bank maintains a policy rate of 0%; the rate on 10-year Swiss government bonds has been in the 0.5 – 0.7% range. Why can’t we have Swiss-like interest rates in the U.S.? Is it merely intransigence on the part of the Fed, as Trump would have us believe?

No. Inflation in Switzerland is near zero, so in terms of real yields, the gap between U.S. and Swiss rates is closer to 1.4%, rather than 3.8%. But what of the remaining difference? Swiss government debt, even more than U.S. Treasury debt, attracts investors due to the nation’s “safe-haven” status. Also, U.S. yields are elevated by our ballooning federal debt and uncertainties related to trade policy. Economic growth is also somewhat stronger in the U.S., which tends to elevate yields.

These factors give the Fed reason to be cautious about cutting its target rate. It needs evidence that inflation will continue to trend down, and that policy uncertainties can be resolved without reigniting inflation.

Euro Area: The European Central Bank’s (ECB) refinancing rate is now 2.15%. Meanwhile, the 10-year German Bund is yielding around 2.6%, so both short-term and long-term rates in the Euro area are lower than in the U.S. In this case, the difference relative to U.S. rates is not large, nor is it likely attributable to lower expected inflation. Instead, sluggish growth in the EU helps explain the gap. Federal deficits and the ongoing issuance of new Treasury debt also keep U.S. yields higher. Treasury yields may also reflect a premium for volatility due to heavier reliance on foreign investors and private funds, who tend to be price sensitive.

Japan: The Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) policy rate is currently 0.5%. Yields on Japanese 10-year government bonds have recently traded just below 1.5%. Expected inflation in Japan has been around 2.5% this year, which means that real yields are sharply negative. The BOJ has tightened policy to bring inflation down. The nearly 3% gap between U.S. and Japanese bond yields reflects very weak economic growth in Japan. In addition, despite a very high debt to GDP ratio, the depressed value of the yen discourages investment abroad, helping to sustain heavy domestic holdings of government debt.

Blame and Backfire

Trump might well understand the limits of the Fed’s control over interest rates, but if he does, then this is exclusively a case of scapegoating. Cross-country differences in interest rates represent equilibria that balance an array of complex conditions. These range from disparate rates of inflation, the strength of economic growth, currency values, fiscal imbalances, and the character of the investor base. .

Investor expectations obviously play a huge role in all this. A central bank like the Fed cannot dictate long-term yields, and it can do much more harm than good by attempting to push the market where it does not want to go. That type of aggressiveness can spark changes in expectations that undermine policy objectives. It’s childish and destructive to insist that interest rates can and should be as low in the U.S. as in countries facing much different circumstances.