Tags

Administrative State, Certainty Equivalent, Consumer Price Index, Discount Rate, John Cochrane, Joshua Rauh, MIT, Modernizing Regulatory Review, Office of Management and Budget, Present Value, Real Interest Rate, Regulatory Impact Analysis, Risk-Free Rate, TIPS, Tradeoffs, Treasury Bonds, Unintended Consequences

Tweaks to the projected costs and benefits of prospective regulations or programs can be a great way to encourage domination of resources and society by the state. Of course, public policy ideas will never receive serious consideration unless their “expected” benefits exceed costs. It’s therefore critical that the validity of cost and benefit estimates — to say nothing of their objectivity — are always subject to careful review. By no means does that ensure that the projections are reasonable, however.

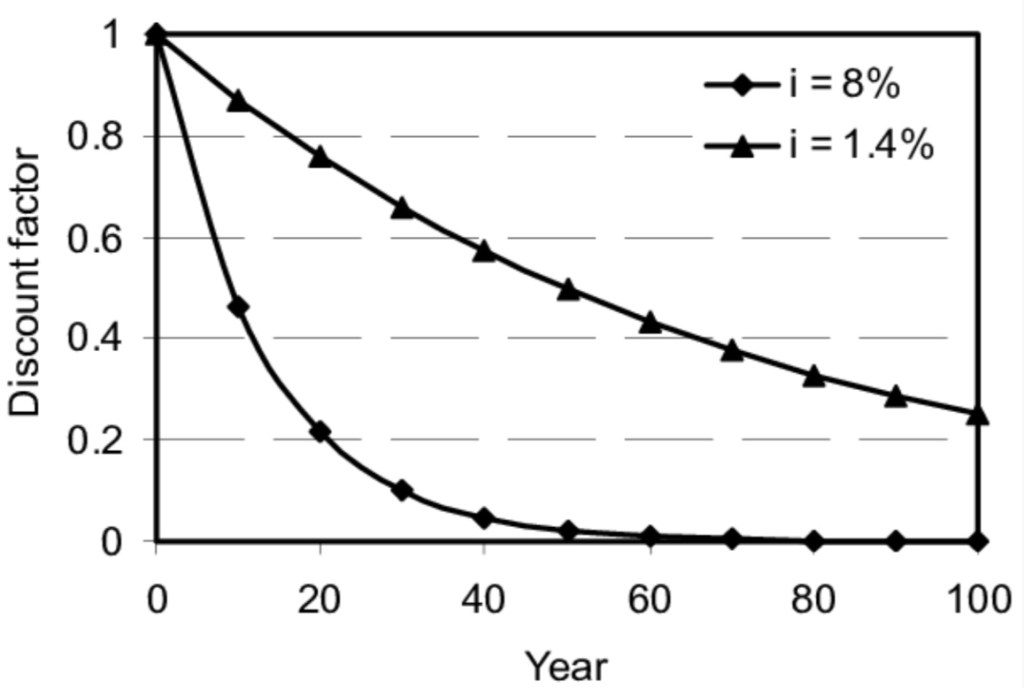

Traditionally less scrutinized is the rate at which the future costs and benefits of a program or regulation are discounted into present value terms. The discount rate can have a tremendous impact on the comparison of costs and benefits when their timing differs significantly, which is usually the case.

Intertemporal Tradeoffs

People generally aren’t willing to forsake present pleasure without at least a decent prospect of future gain. Thus, we observe that the deferral of $1 of consumption today generally brings a reward of more than $1 of future consumption. That’s made possible by the existence of productive opportunities for the use of resources. These opportunities, and the freedom to exploit them, allow a favorable tradeoff at which we transform resources across time for the benefit of both our older selves and our progeny. The interaction of savers and investors in such opportunities results in an equilibrium interest rate balancing the supply and demand for saving.

We can restate the tradeoff to demonstrate the logic of discounting. That is, the promise of $1 in the future induces the voluntary deferral of less than $1 of consumption today. To arrive at the amount of the deferral, the promised $1 in the future is discounted at the consumer’s rate of time preference. The promised $1 must cover the initial deferral of consumption plus the consumer’s perceived opportunity cost of lost consumption in the present, or else the “trade” won’t happen.

Discounting practices are broadly embedded in the economy. They provide a rational basis of evaluating inter-temporal tradeoffs. The calculation of net present values (NPVs) and internal rates of return (the discount rate at which NPV = 0) are standard practices for capital budgeting decisions in the private sector. Public-sector cost-benefit analysis often makes use of discounting methodology as well, which is unequivocally good as long as the process is not rigged.

Government Discounting

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) provides guidance to federal agencies on matters like cost-benefit analysis. As part of a recent proposal that was prompted by executive orders on “Modernizing Regulatory Review” from the Biden Administration, the OMB has recommended revisions to a 2003 Circular entitled “Regulatory Analysis”. A major aspect of the proposal is a downward adjustment to recommended discount rates, largely dressed up as an update for “changes in market conditions”.

Since 2003, the OMB’s guidance on discount rates called for use of a historical average rate on 10-year government bonds. Before averaging, the rate was converted to a “real rate” in each period by subtracting the rate of increase in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The baseline discount rate of 3% was taken from the average of that real rate over the 30 years ending in 2002. There has been an alternative discount rate of 7% under the existing guidance intended as a nod to the private costs of capital, but it’s not clear how seriously agencies took this higher value.

The new proposal seeks to update the calculation of recommended discount rates by using more recent data on Treasury rates and inflation. One aspect of the proposal is to utilize the rate on 10-year inflation-indexed Treasury bonds (TIPS) for the years in which it is available (2003-2022). The first ten years of the “new” 30-year average would use the previous methodology. However, the proposal gives examples of how other methods would change the resulting discount rate and requests comments on the most appropriate method of updating the calculation of the 30-year average.

The new baseline discount rate proposed by OMB is 1.7%, and it is lower still for very distant flows of benefits. This is intended as a real, after-tax discount rate on Treasury bonds. It represents an average (and ex post) risk-free rate on bonds held to maturity over the historical period in question, calculated as described by OMB. However, like the earlier guidance, it is not prospective in any sense. And of course it is quite low!

Our Poor Little Rich Ancestors

The projected benefits of regulations or other public initiatives can be highly dubious in the first place. Unintended consequences are the rule rather than the exception. Furthermore, even modest economic growth over several generations will leave our ancestors with far more income and wealth than we have at our disposal today. That means their ability to adapt to changes will be far superior, and they will have access to technologies making our current efforts seem quaint.

Now here’s the thing: discounting the presumed benefits of government intervention at a low rate would drastically inflate their present value. John Cochrane uses an extreme case to illustrate the point. Suppose a climate policy is projected to avoid costs equivalent to 5% of GDP 100 years from now. Those avoided costs would represent a gigantic sum! By then, at just 2% growth, real GDP will be over seven times larger than this year’s output. Cochrane calculates that 5% of real GDP in 2123 is equivalent to 37% of 2023 real GDP. And the presumed cost saving goes on forever.

We can calculate the present value of the climate policy’s benefits to determine whether it’s greater than the proposed cost of the policy. Let’s choose a fairly low discount rate like … oh, say zero. In that case, the present value is infinite, and it is infinite at any discount rate below 2% (such as 1.7%). That’s because the benefits grow at 2% (like real GDP) and go on forever! That’s faster than the diminishing effect of discounting on present value. In mathematical terms, the series does not converge. Of course, this is not discounting. It is non-discounting. Cochrane’s point, however, is that if you take these calculations seriously, you’d be crazy not to implement the policy at any finite cost! You shouldn’t mind the new taxes at all! Or the inflation tax induced by more deficit spending! Or higher regulatory costs passed along to you as a consumer! So just stop your bitching!

Formal Comments to OMB

If Cochrane’s example isn’t enough to convince you of the boneheadedness of the OMB proposal, there are several theoretical reasons to balk. Cochrane provides links to a couple of formal comments submitted to OMB. Joshua Rauh of the Stanford Business School details a few fundamental objections. His first point is that a regulatory impact analysis (RIA), or the evaluation of any other initiative, “should be based on market conditions that prevail at the time of the RIA”. In other words, the choice of a discount rate should not rely on an average over a lengthy historical period. Second, it is unrealistic to assume that the benefits and costs of proposed regulations are risk-free. In fact, unlike Treasury securities, these future streams are quite risky, and they are not tradable, and they are not liquid.

Rauh also notes that the OMB’s proposed decline in discount rates to be applied to benefits or cash flows in more distant periods has no reliable empirical basis. He believes that results based on a constant discount rate should at least be reported. Moreover, agencies should be required to offer justification for their choice of a discount rate relative to the risks inherent in the streams of costs and benefits on any new project or rule.

Rauh is skeptical of recommendations that agencies should add a theoretical risk premium to a risk-free rate, however, despite the analytical superiority of that approach. Instead, he endorses the simplicity of the OMB’s previous guidance for discount rates of 3% and 7%. But he also proposes that RIAs should always include “the complete undiscounted streams of both benefits and costs…”. If there are distributions of possible cost and benefit streams, then multiple streams should be included.

Furthermore, Rauh says that agencies should not recast streams of benefits in the form of certainty equivalents, which interpose various forms of objective functions in order to calculate a “fair guarantee”, rather than a range of actual outcomes. Instead, Rauh insists that straightforward expected values should be used, This is for the sake of transparency and to enable independent assessment of RIAs.

Another comment on the OMB proposal comes from a group of economists at MIT. They have fewer qualms than Rauh regarding the use of risk-adjusted discount rates by government agencies. In addition, they note that risk in the private sector can often be ameliorated by diversification, whereas risks inherent in public policy must be absorbed by changes in taxes, government spending, or unintended costs inflicted on the private sector. Taxpayers, those having stakes in other programs, and the general public bear these risks. Using Treasury rates for discounting presumes that bad outcomes have no cost to society!

Conclusion

Discounting the costs and benefits of proposed regulations and other government programs should be performed with discount rates that reflect risks. Treasury rates are wholly inappropriate as they are essentially risk-free over time horizons often much shorter than the streams of benefits and costs to be discounted. The OMB proposal might be a case of simple thoughtlessness, but I doubt it. To my mind, it aligns a little too neatly with the often expansive agenda of the administrative state. It would add to what is already a strong bias in favor of regulatory action and government absorption of resources. Champions of government intervention are prone to exaggerate the flow of benefits from their pet projects, and low discount rates exaggerate the political advantages they seek. That bias comes at the expense of the private sector and economic growth, where inter-temporal tradeoffs and risks are exploited only at more rational discounts and then tested by markets.