Tags

ADP Employment Report, Core PCE Deflator, Covid Restrictions, David Beckworth, Donald Trump, Dual Mandate, Employment Mandate, FAIT, Federal Funds Target, Flexible Average Inflation Targeting, Inflation Bias, Inflation Target, Jerome Powell, Mark Sobel, Monetary policy, Policy Asymmetry, Price Stability, Quantitative Tightening, Robert Brusca, Scott Sumner, Tariffs

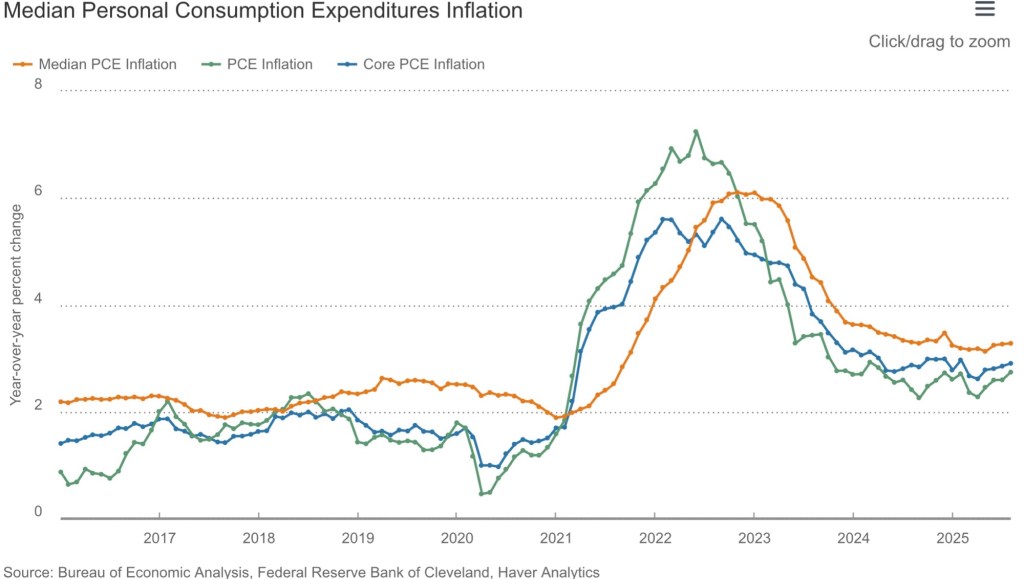

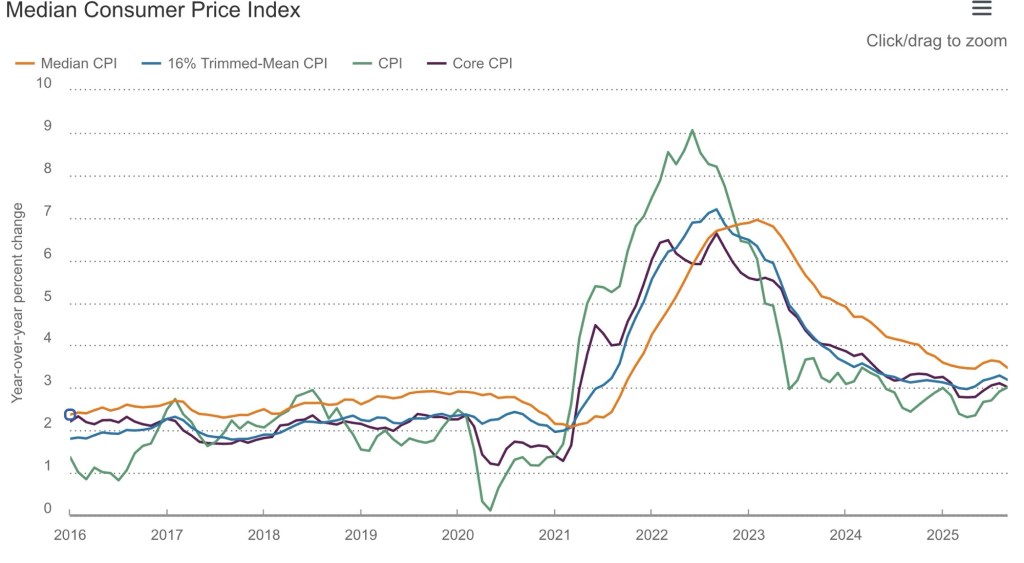

Inflation leveled off below 3% in 2024 and has drifted around the 3% level in 2025. The rate of increase in the core PCE (Personal Consumption Deflator) is the inflation measure of most interest to the Federal Reserve as a policy reference, but advances in the core CPI (Consumer Price Index) have settled at about the same level. The core inflation rates exclude food and energy prices due to the volatility of those components, but even with food and energy, inflation in the PCE and the CPI have been running near 3%.

It’s a 2% Target… Or Is It?

The Fed continues to maintain that its “official” inflation target is 2% for the core PCE. However, the central bank is now easing policy despite inflation running a full percentage point faster than the target. The rationale turns on the Fed’s dual mandate to maintain both “price stability” and full employment, goals that are not always compatible.

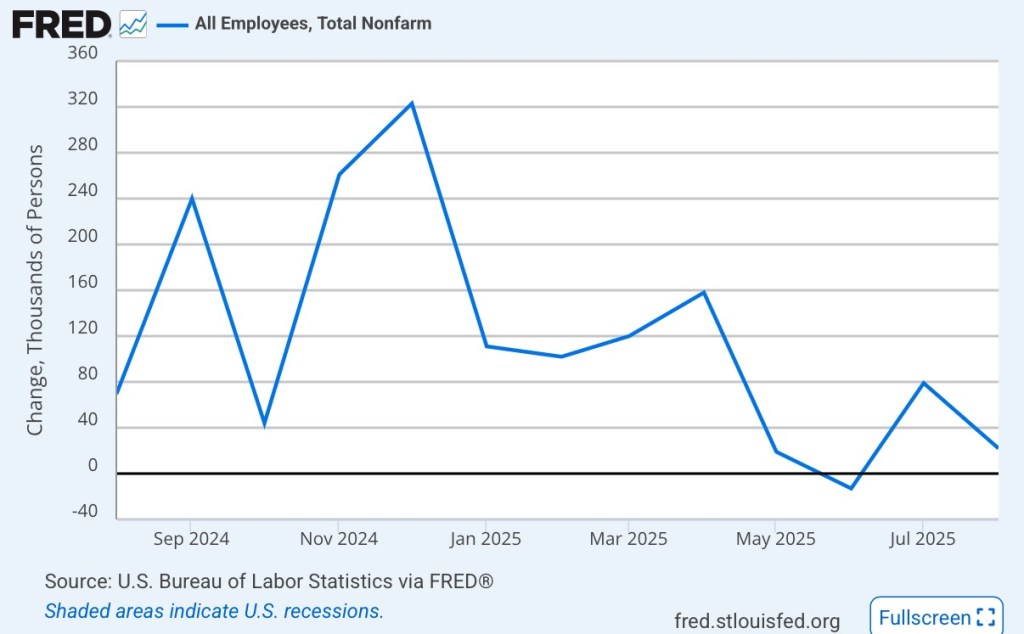

Currently, the labor market is showing signs of weakness, so the Fed has elected to ease policy by guiding the federal funds rate downward, and by putting a stop to run-off in its balance sheet holdings of securities. The latter ends a brief period of so-called quantitative tightening.

Just a couple of months ago, the central bank announced a new emphasis on targeting 2% inflation in the long run, with notable differences from the “flexible average inflation targeting” (FAIT) that it claimed to have adopted in 2020. In some respects, the Fed appeared to be giving more primacy to the “2%” definition of price stability than to the full employment mandate. Yet the “new approach” still allows plenty of wiggle room and might not differ much from the approach followed prior to FAIT.

No FAITful Error

Here’s how David Beckworth characterizes the way FAIT ultimately played out. He says that in practice the Fed took:

“… an asymmetric approach to the dual mandate: It would implement makeup policy on misses below the inflation target, and it would respond to shortfalls from maximum employment. These asymmetries, while well- intended, created an inflationary bias that caused FAIT to fail the ‘stress test’ of the 2021–22 inflation surge. This failure caused the Fed to effectively abandon FAIT in early 2022 and become a single-mandate central bank focused on price stability.“

Scott Sumner says the Fed never really really practiced FAIT to begin with. It should have been a symmetric policy, but it wasn’t. During 2021-22, the Fed did not attempt to correct for rising inflation. Instead, it focused on the recessionary effects of Covid and the impingements of Covid-era restrictions on employment.

Clearly, Covid was a shock that monetary policy was ill-suited to address without reinforcing inflation. Furthermore, the pandemic inflation was thought by the Fed to be transitory, but easing policy was a critical error. Stimulating demand via monetary accommodation gave inflation more permanence than the Fed apparently expected.

Lost In the Tea Leaves Again

While a strong commitment to price stability is welcome, it’s not clear that is what’s guiding the Fed’s decisions at the moment. Again, the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge has flattened out at around 3%. However, with uncertainty about tariffs and tariff pass throughs in 2026, the weak dollar, and unrelenting Treasury borrowing, easier monetary conditions could well set the stage for persistent inflation above 3%, despite the official 2% target. That might help explain the failure of longer-term interest rates to decline in the wake of the Fed’s latest quarter-point cut in the federal funds target in October.

Suspicious Minds

Speculation that the Fed is allowing its true inflation target to creep upward is hardly new. Back in June, former New York Fed economist Robert Brusca noted the following:

“A Cleveland Fed survey already has the business community thinking that the REAL target for inflation is 2.5%.”

More recently, Mark Sobel of the Official Monetary and Fiscal Institutions Forum stated that the real target, for now, is probably 3%:

“But could the Fed stealthily and unintentionally end up near 3%? Even apart from above-target inflation in recent years, short- and longer-term structural forces are at play that could usher in slightly higher inflation, notwithstanding Fed speeches on the sanctity of the 2% inflation target.“

Chewing On Data

It’s pretty clear that the Fed has become a skittish about the pace of the real economy, lending more weight to the full employment part of its dual mandate. Employment growth slowed over the past year, partly due to government employee buy-outs and separations of illegal immigrants from their employers. The last official employment report was in early September, however, so the nonfarm payroll data is two months out-of-date:

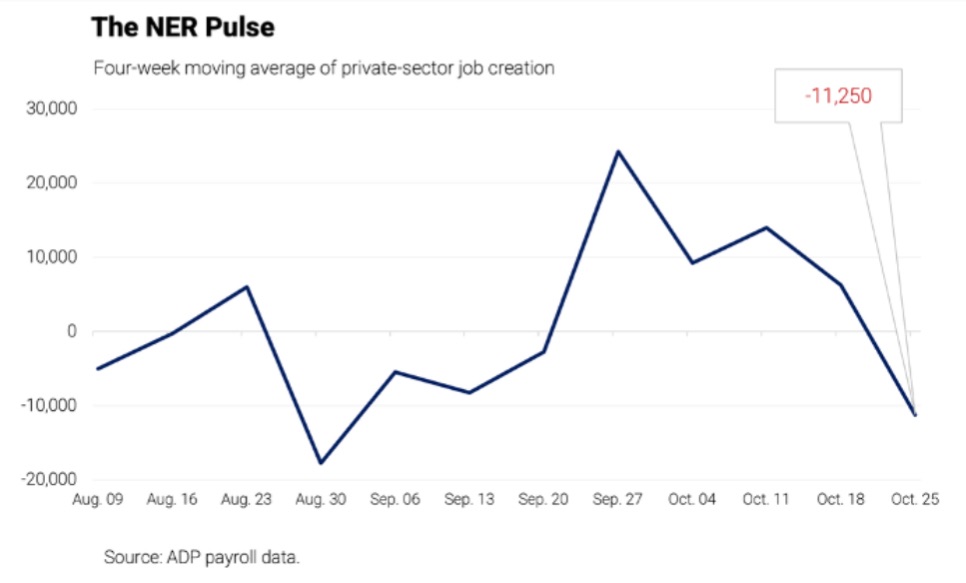

Private payroll growth from ADP over the past two months has not looked especially encouraging:

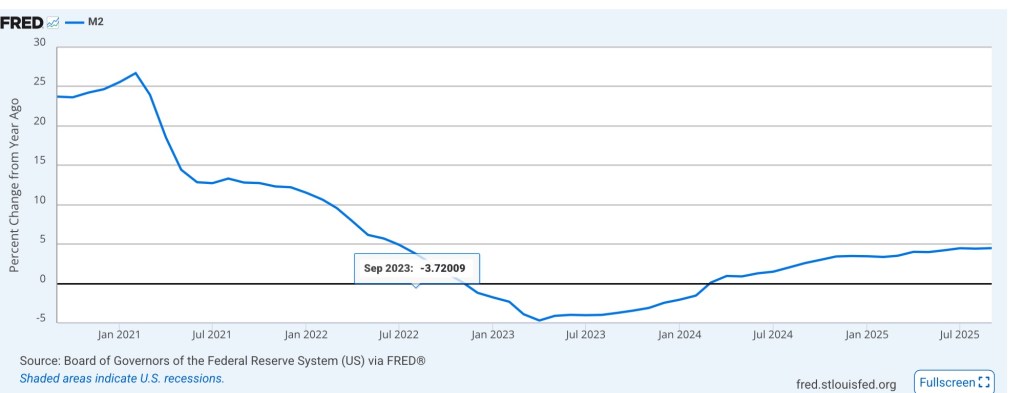

Tariffs and weakened profit margins have likely had a contractionary effect, and the six-week government shutdown just ended will shave 0.5% or more off fourth quarter GDP growth. Furthermore, while money (M2) growth has accelerated over the past year, it remains fairly restrained.

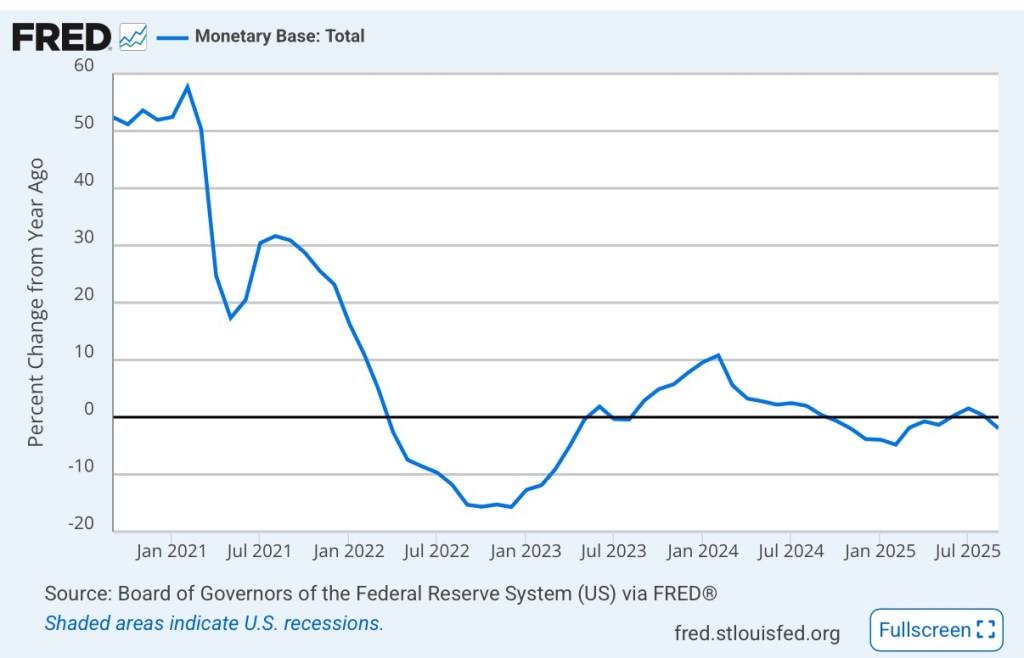

And the monetary base has been pretty flat for most of 2025:

We’ll see where these aggregates go from here. The extended “restraint” might now be of some concern to the Fed, given recent doubts about employment and economic growth. Still, in October, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said that another quarter-point cut in the federal funds rate target in December was not a foregone conclusion. That statement seems to have worried equity investors while offering little solace to bond investors.

Aborted Landing

If (and as long as) the Fed gives primacy or greater weight in its policy deliberations to employment than inflation, it might as well have adopted an inflation target of 3% or more. The additional erosion in purchasing power wrought by that leniency is bad enough, but the effect of monetary policy on the real side of the economy is more poorly understood than its effect on nominal variables. The Fed’s shift in priorities is both unreliable on the real side and dangerous in terms of price stability. These concerns are even more salient given the upcoming appointment (in May) of a new Fed Chairman by President Trump, who seems eager for easy money.