Tags

BBVA Research, Bernie Sanders, Credit Card Lending, Credit Limits, Credit Report, Dodd-Frank, Donald Trump, Federal Reserve, Interest Rate Caps, J.D. Tuccille, Josh Hawley, Late Fees, Loan Sharks, Minimum Payments, Or, PATRIOT Act, Pawn Shops, Payday Loans, Purchase Limits, Relationship Requirements, Revolving Balances, Thin Files, Title Loans, Usury Laws

If you want to induce a shortage, a price ceiling is a reliable way to do it. Usury laws are no exception to this rule. Private credit can be supplied plentifully to borrowers only when lenders are able to charge rates commensurate with other uses of their funds. Importantly, the rate charged must include a premium for the perceived risk of nonpayment. That’s critical when extending credit to financially-challenged applicants, who are often deserving but may be less stable or unproven.

No doubt certain lenders will seek to exploit vulnerable borrowers, but those borrowers are made less vulnerable when formal, mainstream sources of credit are available. A legal ceiling on the price of credit short-circuits this mechanism by restricting the supply to low-income borrowers, many of whom rely on credit cards as a source of emergency funds.

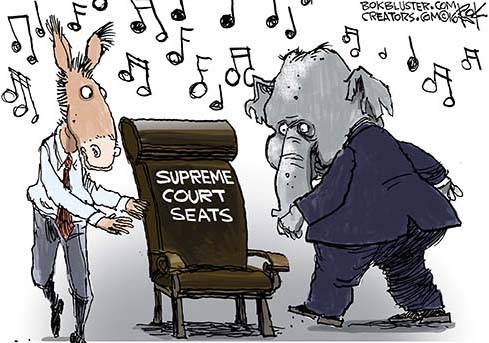

A couple of odd bedfellows, Senators Josh Hawley (R-MO) and Bernie Sanders (D-CT), are cosponsoring a bill to impose a cap of 10% on credit card interest rates. Sanders is an economic illiterate, so his involvement is no surprise. Hawley is otherwise a small government conservative, but in this effort he reveals a deep ignorance. Unfortunately, President Trump would be happy to sign their bill into law if it gets through Congress, having made a similar promise last fall during the campaign. Unfortunately, this is a typically populist stance for Trump; as a businessman he should know better.

Many consumers in the low-income segment of the market for credit have thin credit reports, a few delinquencies, or even defaults. Most of these potential borrowers struggle with expenses but generally meet their obligations. But even a few with the best intentions and work ethic will be unable to pay their debts. The segment is risky for lenders.

Card issuers might be able to compensate along a variety of margins. These include high minimum payments, stiff fees for late payments, tight credit limits (on lines, individual purchases, or revolving balances), deep relationship requirements, and limits on rewards. However, the most straightforward option for covering the risk of default is to charge a higher interest rate on revolving balances.

The total return on assets of credit-card issuing banks in 2023 was 3.33%, more than twice the 1.35% earned at non-issuing banks, as reported by the Federal Reserve. But that difference in profitability is well aligned with the incremental risk of unsecured credit card lending. According to BBVA Research:

“… studies confirm that higher interest rates on credit cards are not related to limited market competition but to greater levels of risk relative to other banking activities backed or secured by collateral. … In fact, an investigation into the risk-adjusted returns of credit cards banks versus all commercial banks suggests that over the long term, credit cards banks do not enjoy a significant advantage. … the market is characterized by participants that operate a high-risk business that requires elevated risk premiums.”

So card issuers are not monopolists. They face competition from other banks, often on the basis of non-rate product features, as well as “down-market” lenders who “specialize” in serving high-risk borrowers. These include payday lenders, pawn shop operators, vehicle title lenders, refund anticipation lenders, and informal loan sharks, all of whom tend to demand stringent terms. People turn to these alternatives and other informal sources when they lack better options. Hawley, Sanders, and Trump would unwittingly throw more credit-challenged consumers into this tough corner of the credit market if the proposed legislation becomes law.

Much of this was discussed recently by J.D. Tuccille, who writes that many consumers:

“… find banks, credit card companies, and other mainstream institutions rigid, uninterested in their business, and too closely aligned with snoopy government officials. Often, the costs and requirements imposed by government regulations make doing business with higher-risk, lower-income customers unattractive to mainstream finance.

‘The regulators are causing the opposite of the desired effect by making it so dangerous now to serve a lower-income segment,’ JoAnn Barefoot, a former federal official, including a stint as deputy controller of the currency, told the book’s author. She emphasized red tape that makes serving many potential customers a legal minefield“

Tuccille offers a revealing quote attributed to a bank official from a 2015 article in the Albuquerque Journal:

“‘Banking regulations stemming from the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 and the Patriot Act of 2001 have created an almost adversarial credit environment for people whose finances are in cash.‘“

In other words, for some time the government has been doing its damnedest to choke off bank-supplied credit to low-income and risky borrowers, many of whom are deserving. It’s tempting to say this was well-intentioned, but the truth might be more sinister. Onerous regulation of lending practices at mainstream financial institutions, including caps on credit card interest rates, is political gold for politicians hoping to exploit populist sentiment. “Good” politics often hold sway over predictable but unintended consequences, which later can be blamed on the very same financial institutions.