Tags

000 Mules, 340B Program, Affordable Care Act, Community Pricing, Continuing Resolution, Cross Subsidies, Federal Medical Assistance Percentages, Gender-Affirming Care, Government Shutdown, Guaranteed Renewability, Health Status Insurance, Jane Menton, John Cochrane, Medicaid, Medicare, Michael Cannon, Nationalized Health Care, Obamacare, Obamacare Expanded Subsidies, Obamacare Tax Credits, One Big Beautiful Bill Act, Peter G. Peterson Foundation, Portability, Pre-Existing Conditions, Right To Health Care, Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, Third-Party Payers

The impasse at the heart of the seemingly unending government shutdown revolves around health care subsidies.

First, there is disagreement about whether to extend the expanded Obamacare subsidies promulgated during the COVID pandemic. That expansion allowed individuals earning more than four times the federal poverty level (the original limit under the Affordable Care Act (ACA)) to receive tax credits for the purchase of health coverage on the exchange “marketplace”. Republicans find this highly objectionable. Many of them also object that the subsidies help pay for “essential health benefits” under the ACA that include so-called gender-affirming care.

Democrats and the insurance lobby would very much like to reinstate or retain the tax credits. The ten-year cost of extending them is more than $400 billion. Incredibly, it turns out that roughly 40% of individuals taking those tax credits did not file a medical claim in 2024. It was pure cash for insurers at the expense of taxpayers.

Second, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBB), among other things, restricts access to Medicaid by imposing work or job search requirements for overall eligibility. It also formally denies coverage to illegal aliens. This, of course, is opposed by Democrats, who insist that those requirements be rescinded.

Health Care Central Planning

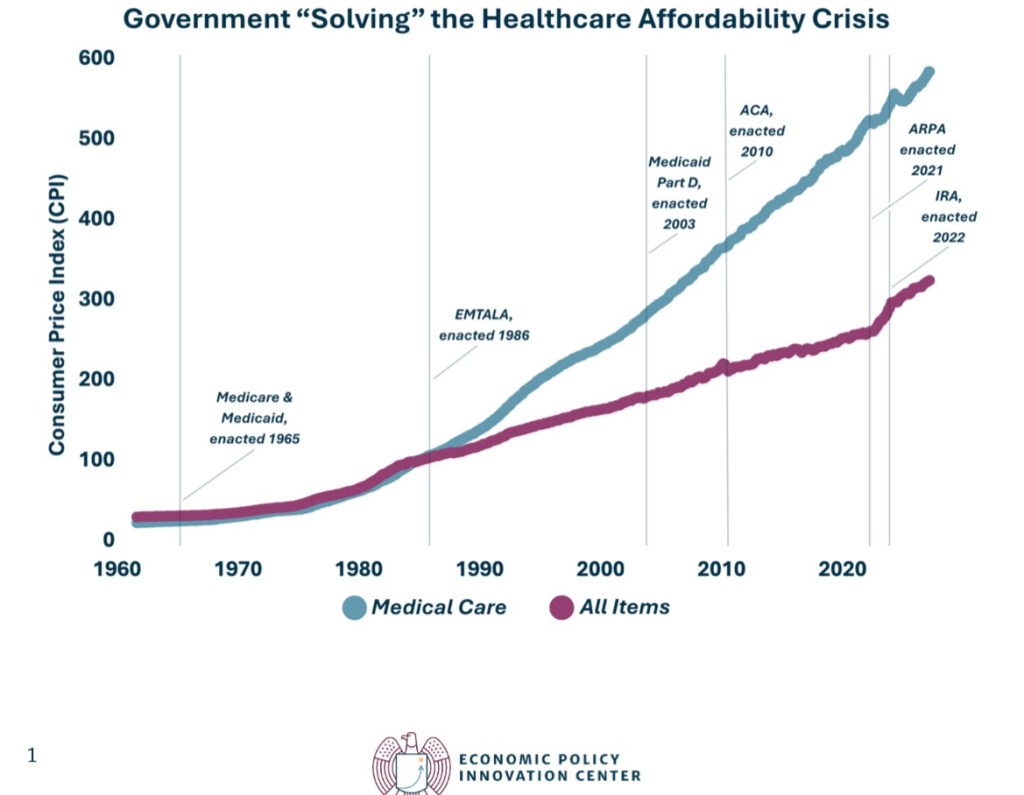

These issues are part of a much larger debate over government dominance of the health care system. Almost every institutional arrangement in health care coverage and delivery is dictated by rules and practices imposed by government, and it would seem they are intentionally designed to escalate costs and compromise the delivery of care. The chart at the top of this post illustrates, in a high-level way, the futility of these efforts.

Medicare and Medicaid dominate government health care spending, as this report from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation shows. However, that strict budgetary view greatly understates the control government now exerts on the health care sector.

Medical Free Market Myth

Michael Cannon recently emphasized the irony of the persistent myth of a U.S. free market in health care:

“… government controls a larger share of health spending in the United States than in 27 out of 38 OECD-member nations, including the United Kingdom (83%) and Canada (73%), each of which has an explicitly socialized health-care system. When it comes to government control of health spending, the United States is closer to communist Cuba (89%) than the average OECD nation (75%).

“Nor does the United States have market prices for health care. Direct government price-setting, price floors, and price ceilings determine prices for more than half of U.S. health spending, including virtually all health-insurance premiums.“

ObamaSnare

Government “control” takes a variety of forms, including regulatory intrusions under the aegis of Obamacare. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), as its name implies, was sold as a way to keep health care and health insurance costs affordable. And it was billed as a way to extend individual health care coverage to the previously uninsured population. It failed badly on the first count and met with only limited success on the second.

One leg upon which the ACA stood was kicked away in 2017: the penalty for violating the Act’s individual mandate for health coverage was eliminated by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). The penalty was arguably unconstitutional as a tax on non-commerce, or the non-purchase of insurance on the exchange. However, the Supreme Court had ruled narrowly in favor of the penalty in 2012, claiming that it was within the scope of Congress’ taxing power. Following passage of the TCJA, however, the toothlessness of the mandate caused the risk pool to deteriorate. This was aggravated by the ACA’s insistence on comprehensive coverage, which applies not just to policies sold on the Obamacare exchange, but to almost all private health insurance sold in the U.S.

A well-functioning marketplace would instead have promoted the availability of more moderately-priced coverage options. Ultimately, subsidies were all that prevented a broad exit from the marketplace. But they did nothing to slow the escalation in coverage costs and deteriorating quality of coverage and care:

“The result has been a race to the bottom in terms of the quality of insurance coverage for the sick. …individual-market provider networks [have] narrow[ed] significantly… They have eroded coverage through ‘poor coverage for the medications demanded by [the sick]’ … higher deductibles and copayments; mandatory drug substitutions and coverage exclusions for certain drugs; more frequent and tighter preauthorization requirements; highly variable coinsurance requirements; inaccurate provider directories; and exclusions of top specialists, high-quality hospitals, and leading cancer centers from their networks. ….

“The healthy suffer, too. … ‘currently healthy consumers cannot be adequately insured against the negative shock of transitioning to one of the poorly covered chronic disease states.’ A coalition of dozens of patient groups has complained that this dynamic ‘completely undermines the goal of the [Affordable Care Act].’”

Price Distortions

Cannon emphasizes another persistent myth: that government sets prices at levels that would prevail in a free market. Here is one baffling aspect of the many prices set by government for individual services under the Medicare and Medicaid programs.

“One of the more striking indications of widespread mispricing is that Medicare routinely sets different prices for identical items depending solely on who owns the facility.“

For example, ambulatory surgical centers are compensated much less for the same services as hospitals. The same is true of compensation for skilled nursing facilities vs. long-term care hospitals, and there appears to be no economic rationale for the differences. Furthermore, it’s an open secret that Medicare sets higher prices for lower-cost providers (and treatment of lower-cost patients). As Cannon notes, this explains the rapid growth of specialty hospitals owned by physicians.

Cannon provides much more detail on Medicare and Medicaid mis-pricing, including the blunting of patients’ price-sensitivity and the shifting of costs to private payers.

Divorcing Risk and Insurance

The price of insurance and insurer reimbursements are also prescribed by government. Cannon’s discussion includes the ACA’s abolition of risk-based insurance pricing, which is an astonishing case of economic malpractice. Depending on one’s health status, “community pricing” acts as either a price ceiling or a price floor. This creates perverse incentives for both the healthy and the unhealthy. Premiums fall short of the cost of caring for the sick.

The federal government attempts to compensate by subsidizing insurers based on the health status of individuals in their risk pool, but that falls short in terms of the quality of coverage for unhealthy individuals. Thus, both the healthy and taxpayers must shoulder an ever-increasing cost burden of insuring the unhealthy.

Circular Scam

As for Medicaid, certain arrangements drive up the cost of the program to taxpayers. For example, last March I wrote about this apparent scam allowing state governments to inflate their Medicaid costs, qualifying for hundreds of billions of federal matching funds:

“Here’s the gist of it: increases in state Medicaid reimbursements qualify for a federal match at a rate known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAPs). First, increases in Medicaid reimbursements must be funded at the state level. To do this, states tax Medicaid providers, but then the revenue is kicked back to providers in higher reimbursements. The deluge of matching federal dollars follows, and states are free to use those dollars in their general budgets.“

Unfortunately, FMAP reform is not directly addressed in the “clean” Continuing Resolution before Congress, though reduced funding levels might lead to reductions in FMAP percentages.

And Another Circular Scam

John Cochrane is largely in agreement with Cannon’s piece, but he focuses first on cross subsidies flowing to “eligible” hospitals dispensing prescription drugs to low-income patients. These hospitals get the drugs from pharmaceutical companies at a steep discount mandated by the so-called 340B program, but the hospitals then bill insurers (or Medicare and Medicaid), a significant markup over their acquisition cost. The Medicaid expansion under the ACA led to an increase in the number of hospitals eligible for the drug discounts.

But that’s not the end of the story. This arrangement creates an obvious incentive for the drug companies to raise their pre-discounted prices. Another unintended outcome cited by Cochrane is that eligible hospitals do not use the proceeds of their mark-ups to offer better care (or care at a lower cost) to low-income consumers. Instead, the funds tend to be directed to investment accounts. The program also creates another incentive for hospital consolidation.

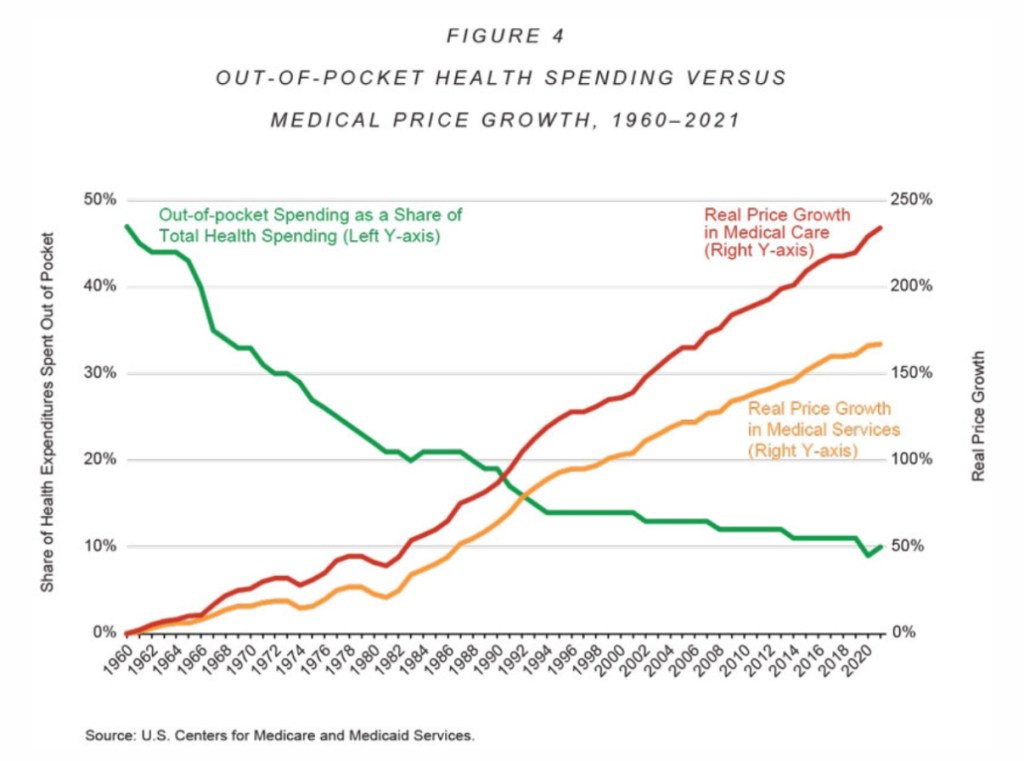

Someone Else’s Money

Unfortunately, the dysfunction in health care goes deeper than Obamacare, Medicare, and Medicaid. The third-party payment system itself has been at the root of cost escalation. It largely relieves consumers of their sovereignty over purchasing decisions, rendering them much less sensitive to variations in price. This can be seen clearly in one of Cannon’s charts, reproduced below:

In addition, the disparate income tax treatment of employer-provided health coverage exacerbates cost escalation. Obviously, employees receiving this deduction can afford higher-quality and more comprehensive coverage. This exemption has acted to drive up the cost of all health care and insurance coverage over the almost nine decades of its existence..

What To Do?

The claim that the U.S. health care system operates within a free market ecosystem is obviously absurd. Together, the Cochrane and Cannon pieces represent something of a gripe session, but it is well deserved. Both authors devote sections to reforms, however. They don’t break new ground in the debate, but the overarching theme of the suggested reforms is to give consumers authority over their health care spending. That means keeping government out of health care in all the myriad ways it now intrudes. It also means that insurers should not have authority to dictate how health care is priced. The key is to allow competition to flourish among health care providers and insurers.

Ending FMAPs and the tax exemption for employer-provided coverage is one thing, but it’s another to contemplate dismantling Medicare, Medicaid, and the many rules and pricing arrangements enforced under Obamacare.

Cochrane takes an accommodating approach to the health care needs of seniors and those in need of a safety net. He calls for Medicare and Medicaid to be replaced with the issuance of vouchers (rather than cash) toward the purchase of affordable private health care plans. Then, health coverage can be provided in a lightly regulated, competitive market without all the distortions and sneaky opportunities for graft embedded in our current entitlements.

Conflicting Rights and Reality

And what of the argument that health care is a human right? That notion is, of course, very popular on the left. The idea subtly shifts a meaningful portion of the responsibility for one’s health onto others, including providers and taxpayers. But smokers, heavy drinkers, reckless drivers, hard drug users, and the avoidably obese should not be led to expect a free ride for risky behaviors.

Of course, it’s not a basic human right to demand, by force of government, involuntary service of health care workers, or that taxpayers give alms, but Cochrane answers with this:

“Yes! It is a basic human right that I should be free to offer my money to a willing physician or hospital, in a brutally competitive and innovative market.”

“Willing” is a key word, and to that we should add “able”, but those are qualifying conditions that markets help facilitate.

Jane Menton has discussed the notion of a human right to health care, wisely explaining that conditions are not always compatible with fulfilling such a right. Her primary concern is the future supply of medical personnel, and an acute shortage of nurses.

“In our current political environment, young people seem to think that claiming something as an entitlement means someone will inevitably show up to do the work.“

To codify a right to health care would be an ill-fared call for a nationalized solution. It would be a prescription for still higher costs and lower quality care. As in any other sector, centralized decision-making leads to misallocated resources, higher costs, and inferior outcomes for patients. Our current mess gives a strong hint of the kind of over-regulated dysfunction that nationalization would bring.

Insurance On Insurability

Pre-existing conditions motivate much of the discussion surrounding a presumed right to health care. Individual portability of group health coverage goes partway in addressing coverage for pre-existing conditions. Portability is mandated by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, but like community rating, it shifts costs to others. That is, the cost of covering pre-existing conditions becomes the responsibility of employers in general, group insurers, and ultimately healthy (and younger) workers.

Given time, the debate over a right to health care can be rendered moot via market processes. Cochrane has long supported the concept of health status insurance. Such policies would allow healthy consumers to guarantee their insurability against the risk of future health contingencies. Guaranteed renewability is a limited form of this type of coverage. General availability of health status insurance contracts, offered regardless of current coverage, could allow for a range of future insurability options at affordable prices. Then, pre-existing conditions would cease to be such a huge driver of cross subsidies.