Tags

Bentley Coffey, Compliance Costs, Congressional Budget Office, Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Conversable Economist, crowding out, Gold Plating, James Whitford, Kieth Carlson, Mandated Investment, Mercatus Center, Patrick A. McLaughlin, Pietro Peretto, Real Clear Markets, Regulatory Burden, Regulatory State, Return on Capital, Robert Higgs, Roger Spencer, Susan E. Dudley, Timothy Taylor, Tyler Richards, Wayne Brough, Zero-Sum Economics

Expanding regulation of the private sector is perhaps the most pernicious manifestation of “crowding out”, a euphemism for the displacement of private activity by government activity. The idea that government “crowds out” private action, or that government budget deficits “crowd out” private investment, has been debated for many years: government borrowing competes with private demand to fund investment projects, bidding interest rates and the cost of capital upward, thus reducing business investment, capital intensity, and the economy’s productive capacity. Taxes certainly discourage capital investment as well. That is the traditional fiscal analysis of the problem.

The more fundamental point is that as government competes for resources and absorbs more resources, whether financed by borrowing or taxation, fewer resources remain available for private activity, particularly if government is less price-sensitive than private-sector buyers.

Is It In the Data?

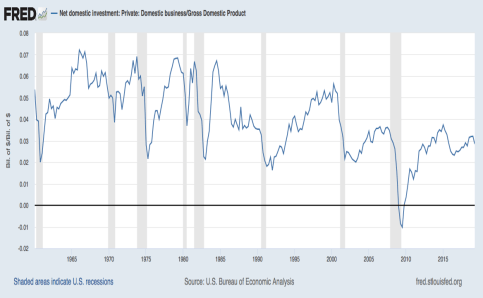

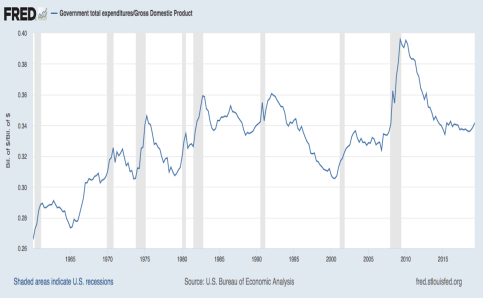

Is crowding out really an issue? Private net fixed investment spending, which represents the dollar value of additions to the physical stock of private capital (and excludes investments that merely replace worn out capital), has declined relative to GDP over many decades, as the first chart below shows. The second chart shows that meanwhile, the share of GDP dedicated to government spending (at all levels) has grown, but with less consistency: it backtracked in the 1990s, rebounded during the early years of the Bush Administration, and jumped significantly during the Great Recession before settling at roughly the highs of the 1980s and early 1990s. The short term fluctuations in both of these series can be described as cyclical, but there is certainly an inverse association in both the short-term fluctuations and the long-term trends in the two charts. That is suggestive but far from dispositive.

Timothy Taylor noted several years ago that the magnitude of crowding out from budget deficits could be substantial, based on a report from the Congressional Budget Office. That is consistent with many of the short-term and long-term co-movements in the charts above, but the explanation may be incomplete.

Regulatory Crowding Out

Regulatory dislocation is not the mechanism traditionally discussed in the context of crowding out, but it probably exacerbates the phenomenon and changes its complexion. To the extent that growth in government is associated with increased regulation, this form of crowding out discourages private capital formation for wholly different reasons than in the traditional analysis. It also encourages malformation — either non-productive or misallocated capital deployment.

I acknowledge that regulation may be necessary in some areas, and it is reasonable to assert that voters demand regulation of certain activities. However, the regulatory state has assumed such huge proportions that it often seems beyond the reach of higher authorities within the executive branch, not to mention other branches of government. Regulations typically grow well beyond their original legislative mandates, and challenges by parties to regulatory actions are handled in a separate judicial system by administrative law judges employed by the very regulatory agencies under challenge!

Measures of regulation and the regulatory burden have generally increased over the years with few interruptions. As a budgetary matter, regulation itself is costly. Robert Higgs says that not only has regulation been expanding for many years, the growth of government spending and regulation have frequently had common drivers, such as major wars, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the financial crisis and Great Recession of the 2000s. In all of these cases, the size of government ratcheted upward in tandem with major new regulatory programs, but the regulatory programs never seem to ratchet downward.

While government competes with the private sector for financial capital, its regulatory actions reduce the expected rewards associated with private investment projects. In other words, intrusive regulation may reduce the private demand for financial capital. Assuming there is no change in the taxation of suppliers of financing, we have a “coincidence” between an increase in the demand for capital by government and a decrease in the demand for capital by business owing to regulatory intrusions. The impact on interest rates is ambiguous, but the long-run impact on the economy’s growth is negative, as in the traditional case. In addition, there may be a reallocation of the capital remaining available from more regulated to less regulated firms.

The Costs of Regulation

Regulation imposes all sorts of compliance costs on consumers and businesses, infringing on many erstwhile private areas of decision-making. The Mercatus Center, a think tank on regulatory matters based at George Mason University, issued a 2016 report on “The Cumulative Cost of Regulations“, by Bentley Coffey, Patrick A. McLaughlin, and Pietro Peretto. It concluded in part:

“… the effect of government intervention on economic growth is not simply the sum of static costs associated with individual interventions. Instead, the deterrent effect that intervention can have on knowledge growth and accumulation can induce considerable deceleration to an economy’s growth rate. Our results suggest that regulation has been a considerable drag on economic growth in the United States, on the order of 0.8 percentage points per year. Our counterfactual simulation predicts that the economy would have been about 25 percent larger than it was in 2012 if regulations had been frozen at levels observed in 1980. The difference between observed and counterfactually simulated GDP in 2012 is about $4 trillion, or $13,000 per capita.”

In another Mercatus Center post, Tyler Richards discusses the link between declining “business dynamism” and growth in regulation and lobbying activity. Richards measures dynamism by the rate of entry into industries with relatively high profit potential. This is consistent with the notion that regulation diminishes the rewards and demand for private capital, thus crowding out productive investment.

Regulation, Rent Seeking, and Misallocation

Some forms of regulation entail mandates or incentives for more private investment in specific forms of physical capital. Of course, that’s no consolation if those investments happen to be less productive than projects that would have been chosen freely in the pursuit of profit. This often characterizes mandates for alternative energy sources, for example, and mandated investments in worker safety that deliver negligible reductions in workplace injuries. Some forms of regulation attempt to assure a particular rate of return to the regulated firm, but this may encourage non-productive investment by incenting managers to “gold plate” facilities to capture additional cash flows.

Regulations may, of course, benefit the regulated in certain ways, such as burdening weaker competitors. If this makes the economy less competitive by driving weak firms out of existence, surviving firms may have less incentive to invest in their physical capital. But far worse is the incentive created by the regulatory state to invest in political and administrative influence. That’s the thrust of an essay by Wayne Brough in Real Clear Markets: “Political Entrepreneurs Are Crowding Out the Entrepreneurs“. The possibility of garnering regulations favorable to a firm reinforces the destructive focus on zero-sum outcomes, as I’ve gone to pains to point out on this blog.

Crowding out takes still other forms: the growth of the welfare state and regulatory burdens tend to displace private institutions traditionally seeking to improve the lives of the poor and disenfranchised. It also disrupts incentives to work and to seek help through those private aid organizations. That is a subject addressed by James Whitford in “Crowding Out Compassion“.

Just Stop It!

President Trump has made some progress in slowing the regulatory trend. One example of the Administration’s efforts is the two-year-old Trump executive order demanding that two regulatory rules be eliminated for each new rule. Thus far, many of the discarded regulations had become obsolete for one reason or another, so this is a clean-up long overdue. Other inventive efforts at reform include moving certain agency offices out of the Washington DC area to locales more central to their “constituencies”, which inevitably would mean attrition from the ranks of agency employees and with any luck, less rule-making. The judicial branch may also play a role in defanging the bureaucracy, like this case involving the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau now before the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, tariffs represent taxation of consumers and firms who use foreign goods as inputs, so Trump’s actions on the regulatory front aren’t all positive.

Conclusion

The traditional macroeconomic view of crowding out involves competition for funds between government and private borrowers, higher borrowing costs, and reduced private investment in productive capital. The phenomenon can be couched more broadly in terms of competition for a wide variety of goods and services, including labor, leaving less available for private production and consumption. The growth of the regulatory state provides another piece of the crowding-out puzzle. Regulation imposes significant costs on private parties, including small businesses that can ill-afford compliance. The web of rules and reporting requirements can destroy the return on private capital investment. To the extent that regulation reduces the demand for financing, interest rates might not come under much upward pressure, as the traditional view would hold. But either way, it’s bad news, especially when the regulatory state seems increasingly unaccountable to the normal checks and balances enshrined in our Constitution.