Tags

Algorithmic Governance, American Affairs, Antitrust, Behavioral Economics, Bryan Caplan, Claremont Institute, David French, Deplatforming, Facebook, Gleichschaltung, Google, Jonah Goldberg, Joseph Goebbels, Mark Zuckerberg, Matthew D. Crawford, nudge, Peeter Theil, Political Legitimacy, Populism, Private Governance, Twitter, Viewpoint Diversity

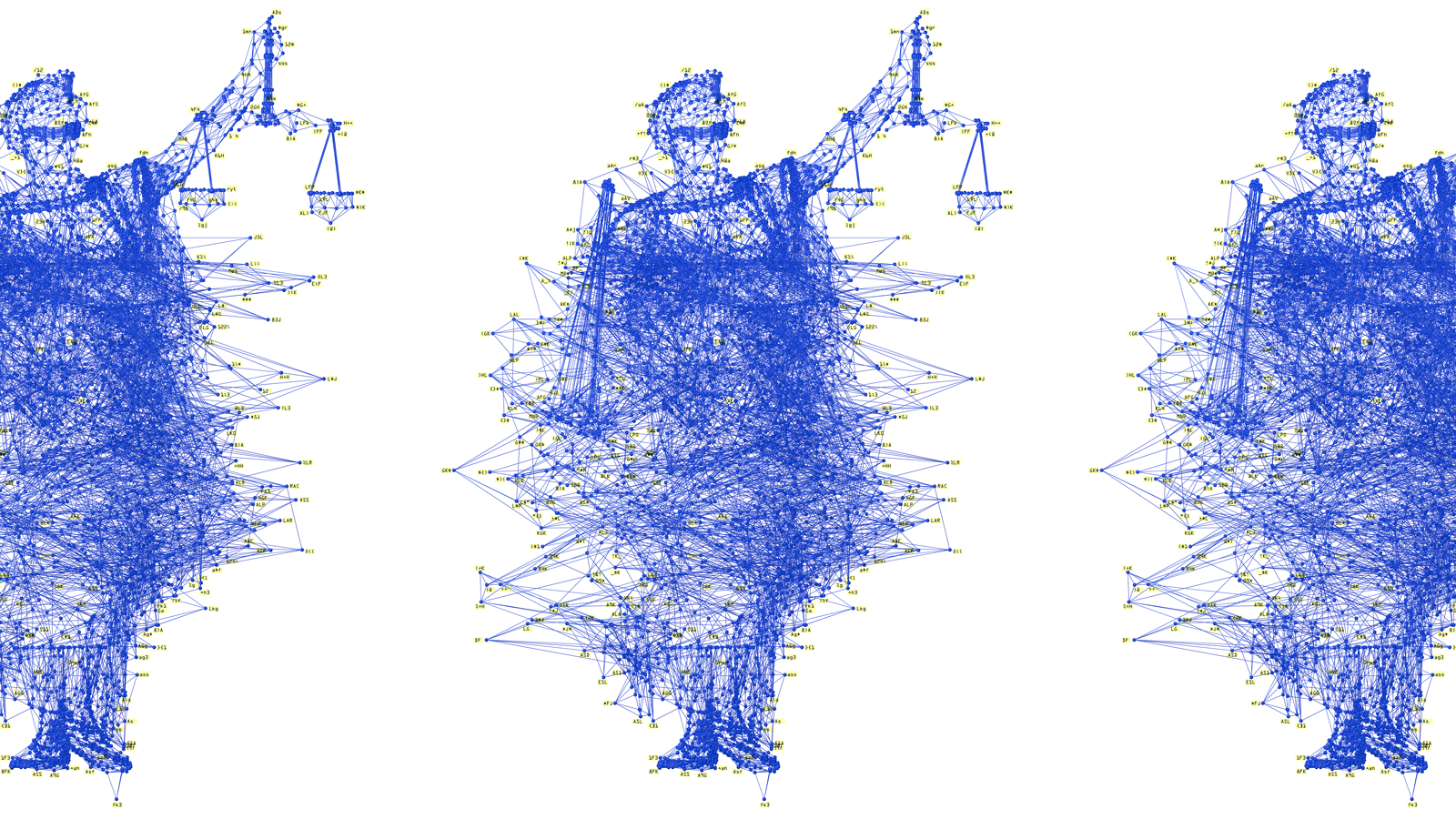

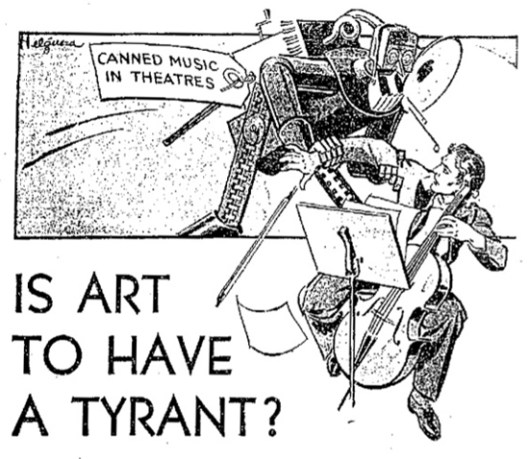

A willingness to question authority is healthy, both in private matters and in the public sphere, but having the freedom to do so is even healthier. It facilitates free inquiry, the application of the scientific method, and it lies at the heart of our constitutional system. Voluntary acceptance of authority, and trust in its legitimacy, hinges on our ability to identify its source, the rationale for its actions, and its accountability. Unaccountable authority, on the other hand, cannot be tolerated. It’s the stuff of which tyranny is made.

That’s one linchpin of a great essay by Matthew D. Crawford in American Affairs entitled “Algorithmic Governance and Political Legitimacy“. It’s a lengthy piece that covers lots of ground, and very much worth reading. Or you can read my slightly shorter take on it!

Imagine a world in which all the information you see is selected by algorithm. In addition, your success in the labor market is determined by algorithm. Your college admission and financial aid decisions are determined by algorithm. Credit applications are decisioned by algorithm. The prioritization you are assigned for various health care treatments is determined by algorithm. The list could go on and on, but many of these “use-cases” are already happening to one extent or another.

Blurring Private and Public Governance

Much of what Crawford describes has to do with the way we conduct private transactions and/or private governance. Most governance in free societies, of the kind that touches us day-to-day, is private or self-government, as Crawford calls it. With the advent of giant on-line platforms, algorithms are increasingly an aspect of that governance. Crawford notes the rising concentration of private governmental power within these organizations. While the platforms lack complete monopoly power, they are performing functions that we’d ordinarily be reluctant to grant any public form of government: they curate the information we see, conduct surveillance, exercise control over speech, and even indulge in the “deplatforming” of individuals and organizations when it suits them. Crawford quotes Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg:

“In a lot of ways Facebook is more like a government than a traditional company. . . . We have this large community of people, and more than other technology companies we’re really setting policies.”

At the same time, the public sector is increasingly dominated by a large administrative apparatus that is outside of the normal reach of legislative, judicial and even executive checks. Crawford worries about “… the affinities between administrative governance and algorithmic governance“. He emphasizes that neither algorithmic governance on technology platforms nor an algorithmic administrative state are what one could call representative democracy. But whether these powers have been seized or we’ve granted them voluntarily, there are already challenges to their legitimacy. And no wonder! As Crawford says, algorithms are faceless pathways of neural connections that are usually difficult to explain, and their decisions often strike those affected as arbitrary or even nonsensical.

Ministry of Wokeness

Political correctness plays a central part in this story. There is no question that the platforms are setting policies that discriminate against certain viewpoints. But Crawford goes further, asserting that algorithms have a certain bureaucratic logic to elites desiring “cutting edge enforcement of social norms“, i.e., political correctness, or “wokeness”, the term of current fashion.

“First, in the spirit of Václav Havel we might entertain the idea that the institutional workings of political correctness need to be shrouded in peremptory and opaque administrative mechanisms because its power lies precisely in the gap between what people actually think and what one is expected to say. It is in this gap that one has the experience of humiliation, of staying silent, and that is how power is exercised.

But if we put it this way, what we are really saying is not that PC needs administrative enforcement but rather the reverse: the expanding empire of bureaucrats needs PC. The conflicts created by identity politics become occasions to extend administrative authority into previously autonomous domains of activity. …

The incentive to technologize the whole drama enters thus: managers are answerable (sometimes legally) for the conflict that they also feed on. In a corporate setting, especially, some kind of ass‑covering becomes necessary. Judgments made by an algorithm (ideally one supplied by a third-party vendor) are ones that nobody has to take responsibility for. The more contentious the social and political landscape, the bigger the institutional taste for automated decision-making is likely to be.

Political correctness is a regime of institutionalized insecurity, both moral and material. Seemingly solid careers are subject to sudden reversal, along with one’s status as a decent person.”

The Tyranny of Deliberative Democracy

Crawford takes aim at several other trends in intellectual fashion that seem to complement algorithmic governance. One is “deliberative democracy”, an ironically-named theory which holds that with the proper framing conditions, people will ultimately support the “correct” set of policies. Joseph Goebbels couldn’t have put it better. As Crawford explains, the idea is to formalize those conditions so that action can be taken if people do not support the “correct” policies. And if that doesn’t sound like Gleichschaltung (enforcement of conformity), nothing does! This sort of enterprise would require:

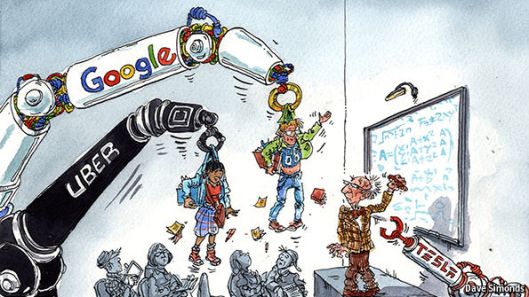

“… a cadre of subtle dialecticians working at a meta-level on the formal conditions of thought, nudging the populace through a cognitive framing operation to be conducted beneath the threshold of explicit argument.

… the theory has proved immensely successful. By that I mean the basic assumptions and aspirations it expressed have been institutionalized in elite culture, perhaps nowhere more than at Google, in its capacity as directorate of information. The firm sees itself as ‘definer and defender of the public interest’ …“

Don’t Nudge Me

Another of Crawford’s targets is the growing field of work related to the irrationality of human behavior. This work resulted from the revolutionary development of experimental or behavioral economics, in which various hypotheses are tested regarding choice, risk aversion, an related issues. Crawford offers the following interpretation, which rings true:

“… the more psychologically informed school of behavioral economics … teaches that we need all the help we can get in the form of external ‘nudges’ and cognitive scaffolding if we are to do the rational thing. But the glee and sheer repetition with which this (needed) revision to our understanding of the human person has been trumpeted by journalists and popularizers indicates that it has some moral appeal, quite apart from its intellectual merits. Perhaps it is the old Enlightenment thrill at disabusing human beings of their pretensions to specialness, whether as made in the image of God or as ‘the rational animal.’ The effect of this anti-humanism is to make us more receptive to the work of the nudgers.”

While changes in the framing of certain decisions, such as opt-in versus opt-out rules, can often benefit individuals, most of us would rather not have nudgers cum central planners interfere with too many of our decisions, no matter how poorly they think those decisions approximate rationality. Nudge engineers cannot replicate your personal objectives or know your preference map. Indeed, externally applied nudges might well be intended to serve interests other than your own. If the political equilibrium involves widespread nudging, it is not even clear that the result will be desirable for society: the history of central planning is one of unintended consequences and abject failure. But it’s plausible that this is where the elitist technocrats in Silicon Vally and within the administrative state would like to go with algorithmic governance.

Crawford’s larger thesis is summarized fairly well by the following statements about Google’s plans for the future:

“The ideal being articulated in Mountain View is that we will integrate Google’s services into our lives so effortlessly, and the guiding presence of this beneficent entity in our lives will be so pervasive and unobtrusive, that the boundary between self and Google will blur. The firm will provide a kind of mental scaffold for us, guiding our intentions by shaping our informational context. This is to take the idea of trusteeship and install it in the infrastructure of thought.

Populism is the rejection of this.”

He closes with reflections on the attitudes of the technocratic elite toward those who reject their vision as untrustworthy. The dominance of algorithmic governance is unlikely to help them gain that trust.

What’s to be done?

Crawford seems resigned to the idea that the only way forward is an ongoing struggle for political dominance “to be won and held onto by whatever means necessary“. Like Bryan Caplan, I have always argued that we should eschew anti-trust action against the big tech platforms, largely because we still have a modicum of choice in all of the services they provide. Caplan rejects the populist arguments against the tech “monopolies” and insists that the data collection so widely feared represents a benign phenomenon. And after all, consumers continue to receive a huge surplus from the many free services offered on-line.

But the reality elucidated by Crawford is that the tech firms are much more than private companies. They are political and quasi-governmental entities. Their tentacles reach deeply into our lives and into our institutions, public and private. They are capable of great social influence, and putting their tools in the hands of government (with a monopoly on force), they are capable of exerting social control. They span international boundaries, bringing their technical skills to bear in service to foreign governments. This week Peter Theil stated that Google’s work with the Chinese military was “treasonous”. It was only a matter of time before someone prominent made that charge.

The are no real safeguards against abusive governance by the tech behemoths short of breaking them up or subjecting them to tight regulation, and neither of those is likely to turn out well for users. I would, however, support safeguards on the privacy of customer data from scrutiny by government security agencies for which the platforms might work. Firewalls between their consumer and commercial businesses and government military and intelligence interests would be perfectly fine by me.

The best safeguard of viewpoint diversity and against manipulation is competition. Of course, the seriousness of threats these companies actually face from competitors is open to question. One paradox among many is that the effectiveness of the algorithms used by these companies in delivering services might enhance their appeal to some, even as those algorithms can undermine public trust.

There is an ostensible conflict in the perspective Crawford offers with respect to the social media giants: despite the increasing sophistication of their algorithms, the complaint is really about the motives of human beings who wish to control political debate through those algorithms, or end it once and for all. Jonah Goldberg puts it thusly:

“The recent effort by Google to deny the Claremont Institute the ability to advertise its gala was ridiculous. Facebook’s blocking of Prager University videos was absurd. And I’m glad Facebook apologized.

But the fact that they apologized points to the fact that while many of these platforms clearly have biases — often encoded in bad algorithms — points to the possibility that these behemoths aren’t actually conspiring to ‘silence’ all conservatives. They’re just making boneheaded mistakes based in groupthink, bias, and ignorance.”

David French notes that the best antidote for hypocrisy in the management of user content on social media is to expose it loud and clear, which sets the stage for a “market correction“. And after all, the best competition for any social media platform is real life. Indeed, many users are dropping out of various forms of on-line interaction. Social media companies might be able to retain users and appeal to a broader population if they could demonstrate complete impartiality. French proposes that these companies adopt free speech policies fashioned on the First Amendment itself:

“…rules and regulations restricting speech must be viewpoint-neutral. Harassment, incitement, invasion of privacy, and intentional infliction of emotional distress are speech limitations with viewpoint-neutral definitions…”

In other words, the companies must demonstrate that both moderators and algorithms governing user content and interaction are neutral. That is one way for them to regain broad trust. The other crucial ingredient is a government that is steadfast in defending free speech rights and the rights of the platforms to be neutral. Among other things, that means the platforms must retain protection under Section 230 of the Telecommunications Decency Act, which assures their immunity against lawsuits for user content. However, the platforms have had that immunity since quite early in internet history, yet they have developed an aggressive preference for promoting certain viewpoints and suppressing others. The platforms should be content to ensure that their policies and algorithms provide useful tools for users without compromising the free exchange of ideas. Good governance, political legitimacy, and ultimately freedom demand it.