Tags

Arthur Laffer, Benn Zycher, Currency Manipulation, Domestic Content Restrictions, Donald Trump, Export Subsidies, Inelastic Demand, Protectionism, Quotas, Stephen Moore, Tariffs, Tax Incidence, Trade Barriers

First, a few more comments re: my speculative musings that Donald Trump’s tariff rampage could ultimately result in a regime with lower trade barriers, at least with a subset of trading partners. Arthur Laffer and Stephen Moore suggested last week that the White House should propose reciprocal free trade with zero barriers and zero subsidies for exports to any country that wishes to negotiate. A more cynical Ben Zycher scoffed at the very possibility, noting that Trump and his lieutenants view any trade deficit as evidence of cheating in one form or another. Zycher is convinced that Trump lacks a basic understanding of the (mostly) benign forces that drive trade imbalances.

I’ve said much the same. Trump’s crazy notions about trade could scuttle negotiations, or he might later accuse a trading partner of cheating on the pretext of a bilateral trade deficit (he’s done so already). And all this is to say nothing of the serious constitutional questions surrounding Trump’s tariff actions.

The mistaken focus on bilateral trade deficits also manifests in certain proposals made during trade negotiations: “Okay, but you’re gonna have to purchase vast quantities of our soybeans every year.” This sort of export promotion is a further drift into industrial planning, and it’s just too much for Trump’s trade negotiators to resist.

This might well turn out as an exercise in self-harm for Trump. However, I’ve also wondered whether his trade hokum is pure posturing, especially because he expressed support for a free trade regime in 2018. Let’s hope he meant it and that he’ll pursue that objective in trade talks. Please, just negotiate lower trade barriers on both sides without the mercantilist baggage.

Which brings me to the theme of this post: it would probably be simpler and more effective for the U.S. to simply drop all of its trade barriers unilaterally. There should be limited exceptions related to national security, but in general we should “turn the other cheek” and let recalcitrant trade partners engage in economic self-harm, if they must.

Okay, Wise Guy, What’s Your Plan?

I have a few friends who bemoan the lack of “fair play” against the U.S. in foreign trade. They have a point, but they also hold an unshakable belief that the U.S. can be just as efficient at producing anything as any other country. They are pretty much in denial that comparative advantages exist in the real world. They are seemingly oblivious to the critical role of specialization in unlocking gains from trade and lifting much of the world’s population out of penury over the past few centuries.

Furthermore, these friends believe that Trump is justified in “retaliating” against countries with whom the U.S. runs trade deficits. If tariffs are so bad, they ask, what would I do instead? Again, here’s my answer:

Eliminate (almost) all barriers to trade imposed by the U.S. Let protectionist nations choke themselves with tariffs/trade barriers.

Before getting into that, I’ll address one fact that is often denied by protectionists.

Yes, a Tariff Is a Tax!

Protectionists often claim that tariffs are not really taxes on U.S. buyers. However, tariffs are charged to buyers of imported goods (often businesses who sell imported goods to consumers or other businesses). In principle, tariffs operate just like a sales tax charged to retail buyers. Both raise government revenue, and they are both excise taxes.

In both cases, the buyer pays but generally bears less than the full burden of the tax. That’s because demand curves slope downward, so sellers (foreign exporters) try to avoid losing sales by moderating their prices in response to the tariff. In both cases, sellers end up shouldering part of the tax burden. How much depends on how buyers react to price: a steep (inelastic) demand curve implies that buyers bear the greater part of the burden of a tariff or sales tax.

People sometimes buy imports due to a lack of substitutes, which implies a steep demand curve. Consumer imports are often luxury items, and well-heeled buyers may be somewhat insensitive to price. Most imports, however, are inputs purchased by businesses, either capital goods or intermediate goods. In the face of higher tariffs, those businesses find it difficult and costly to arrange new suppliers, let alone domestic suppliers, who can deliver quickly and meet their specifications.

These considerations imply that the demand for imports is fairly inelastic (steeper), especially in the short run (when alternatives can’t easily be arranged). Thus, import buyers bear a large portion of the burden in the immediate aftermath of an increased tariff. By imposing tariffs we tax our own citizens and businesses, forcing them to incur higher costs. Correspondingly, if demand is inelastic, an importing country tends to gain more than its trading partners by unilaterally eliminating its own tariffs.

Tariffs on imports also trigger price hikes by import-competing producers. Sometimes this is opportunistic, but even these producers incur higher costs in attempting to meet new demand from buyers who formerly purchased imports. (See this post for an explanation of the costly transition, including a nice exposition of the waste of resources it entails.)

Other Forms of Blood Letting

Beyond tariffs, certain barriers to trade make it more difficult or impossible to purchase goods produced abroad. This includes import quotas and domestic content restrictions. These barriers are often as bad or worse than tariffs because they increase costs and encumber freedom of choice and consumer sovereignty.

Another kind of trade intervention, export subsidies, must be funded by taxpayers. Subsidies are too easily used to protect special interests who otherwise can’t compete. Currency manipulation can both subsidize exports and discourage imports, but it is often unsustainable. The common theme of these interventions is to undermine economic efficiency by shielding the domestic economy from real price signals.

Let Them Tax Themselves

Suppose the U.S. simply turns the other cheek, eliminating all of our own trade interventions with respect to country X despite X’s tariffs and other interventions.

To start with, the existence of barriers means that both countries are unable to exploit all of the benefits of specialization and mutually beneficial trade. Both countries must produce an excess of goods in which they lack a comparative advantage, and both countries produce too few goods in which they have a comparative advantage. Both incur extra costs and produce less output than they could in the absence of trade barriers.

Unilateral elimination of U.S. tariffs and other barriers would reduce high-cost domestic production of certain goods in favor of better substitutes from country X. But Country X gains as well, because it is now able to produce more goods and services for export in which it possesses a comparative advantage. Therefore, the unilateral move by the U.S. is beneficial to both countries.

On the other hand, U.S. export industries are still constrained by country X’s import tax or other restraints. These would-be exporters are no worse off than before, but they are worse off relative to a state in which buyers in country X could freely express their preferences in the marketplace.

What exactly does country X gain from tariffs and other trade burdens on its citizens? It denies them full access to what they deem to be superior goods and services at an acceptable price. It means that resources are misallocated, forcing abstention or the use of inferior or costlier domestic alternatives. Resources must be diverted to relatively inefficient firms. In short, the tariff makes country X less prosperous.

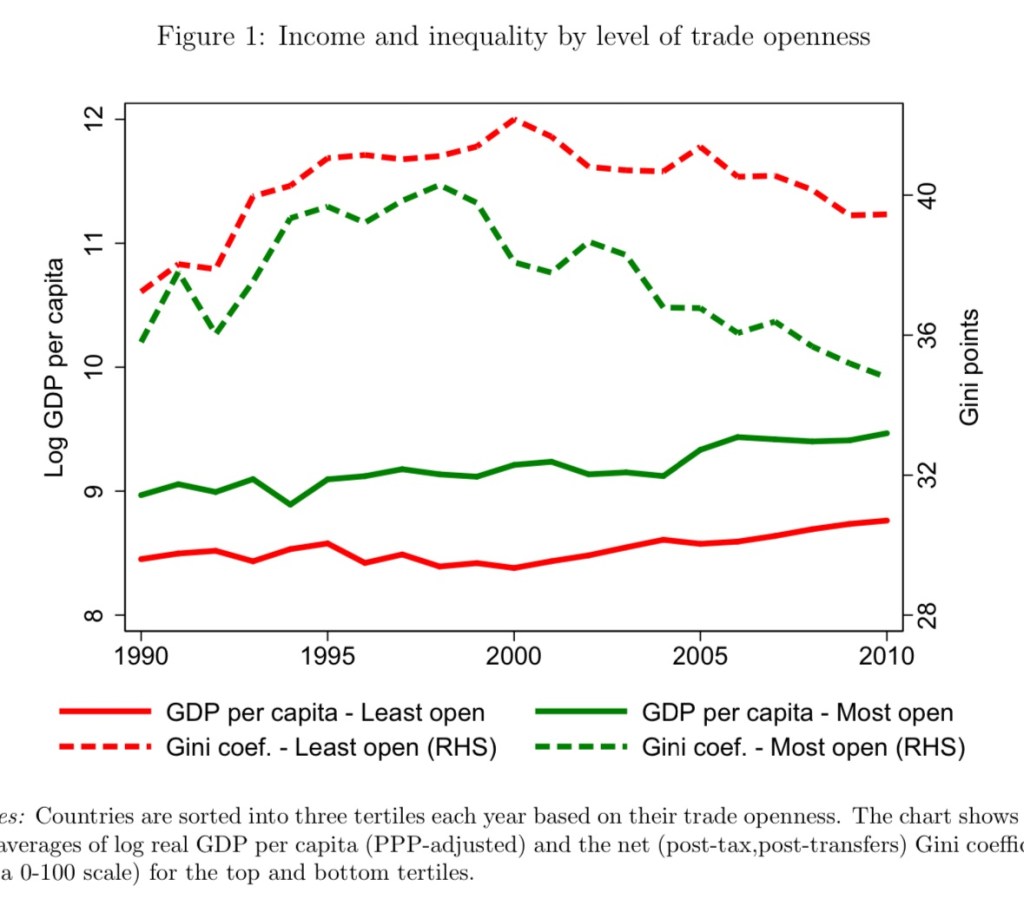

Empirical evidence shows that more open economies (with fewer trade barriers) enjoy greater income and productivity growth. This study found that “trade’s impact on real income [is] consistently positive and significant over time.” See this paper as well. Trade barriers tend to increase the income gap between rich and poor countries. The chart below (from this link) compares real GDP per capita from the top third and bottom third of the distribution of countries on a measure of trade “openness”. Converting logs to levels, the top third has more than twice the average real GDP per capita of the bottom third. And of course, the averaging process mutes differences between very open and very closed trade policies.

The chart also shows that countries more “open” to trade have more equal distributions of income, as measured by their Gini coefficients.

An important qualification is that domestic production of certain goods and services might be critical to national security. We must be willing to tolerate some inefficiencies in that case. It would be foolish to depend on a hostile nation for those supplies, despite any comparative advantage they might possess. It’s reasonable to expect such a list of critical goods and services to evolve with technological developments and changing security threats. However, merely acknowledging this justification leaves the door open for excessively broad interpretations of “critical goods”, especially in times of crisis.

Setting a Good Policy and Example

Here’s an attempt to summarize:

- Tariffs are taxes, and non-tariff barriers inflict costs by distorting prices or diminishing choice

- Trade barriers reduce economic efficiency and produce welfare losses

- Trade barriers deny the citizens of a country the benefits of specialization

- Both countries gain when one trading partner eliminates tariffs on imports from the other

- The demand for imports is fairly inelastic, at least in the short run. Thus, the gain from eliminating a tariff will be skewed toward the domestic importers

- Both countries gain when they agree to eliminate any and all trade barriers

- Across countries, trade barriers are associated with lower incomes, lower income growth, and more unequal distributions of income

The U.S. has a large number of trading partners. Every liberalization we initiate means a welfare gain for us and one trading partner, who would do well to follow our example and reciprocate in full. Not doing so foregoes welfare gains and leads to incremental losses in income relative to more trade-friendly nations. Across all of our trading relationships, a unilateral end to U.S. trade barriers would almost certainly convince some countries to reciprocate. Those that refuse would suffer. Let them self-flagulate. Let them tax themselves.