Tags

Donald Trump, FDIC, Federal Debt, FICA, Fiscal Theory of Price Level, Government Budget Constraint, Insolvency, John Cochrane, Medicare, Penn-Wharton Budget Model, Ponzi Scheme, Primary Surplus, Private Option, Privatization, Social Security, Trust Funds, Unbanked Households

Social Security wasn’t designed as a true saving vehicle for workers. Instead, SS has always been a pay-as-you-go system under which current benefits are funded by the payroll taxes levied on the current employed population. In fact, many Americans earn lousy effective returns on their tax “contributions” (also see here), though low-income individuals do much better than those near or above the median income. Worst of all, under pay-as-you-go, the system can collapse like a Ponzi scheme when the number of workers shrinks drastically relative to the retired population, leading to the kind of situation we face today.

Unfunded Obligations

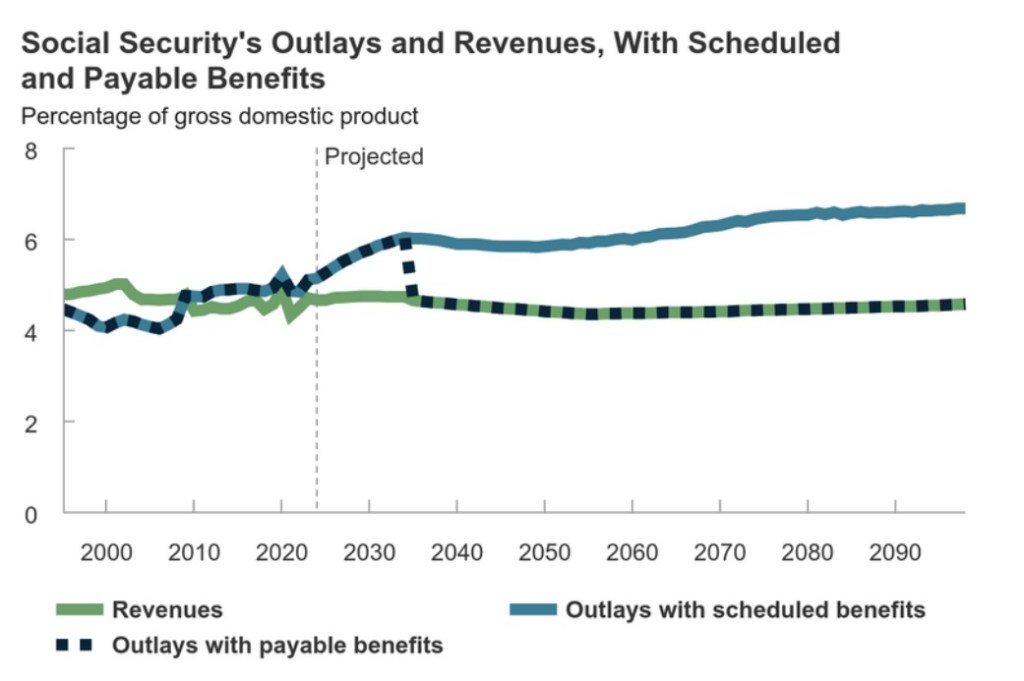

Payroll tax revenue is no longer adequate to pay for current Social Security and Medicare benefits, and the problem is huge: according to the Penn-Wharton Budget Model, the unfunded obligations of Social Security (including old age, survivorship and disability) through 2095 have a present value of $18.1 trillion in constant 2024 dollars (using a discount rate of 4.4%). The comparable figure for Medicare Part A is $18.6 trillion. Together these amount to more than the current national debt.

Barring earlier reform, the Social Security Trust Fund is expected to be exhausted in 2033 (excluding the disability fund). At that point, a 20% reduction in benefits will be required by law. (More on the trust fund below.)

What To Do?

The most prominent reform proposals involve reduced benefits for wealthy beneficiaries, increased payroll taxes on high earners, and an increase in the retirement age. However, President-Elect Donald Trump shows no inclination to make any changes on his watch. This is unfortunate because the sooner the system’s insolvency is addressed, the less draconian the necessary reforms will be.

A neglected reform idea is for SS to be privatized. Many observers agree in principle that current workers could earn better returns over the long-term by investing funds in a conservative mix of equities and bonds. The transition to private accounts could be made voluntary, so that no one is forced to give up the benefits to which they’re “entitled”.

Takers would receive an initial deposit from the government in a tax-deferred account. For participating pre-retirees, ongoing FICA contributions (in whole or in part) would be deposited into their private accounts. They could purchase a private annuity with the balance at retirement if they choose. The income tax treatment of annuity payments or distributions could mimic the current tax treatment of SS benefits.

Given that the balance remaining at death would be heritable, some individuals might be willing to accept an initial deposit less than the actuarial PV of the future SS benefits they’ve accumulated to-date (discounted at an internal rate of return equating future benefits “earned” to-date and contributions to-date). I also believe many individuals would willingly accept a lower initial deposit because they would gain some control over investment direction. Such voluntarily-accepted reductions in initial deposits to personal accounts would mean the government’s issue of new debt would be smaller than the decrease in future benefit obligations.

Nevertheless, funding the accounts at the time of transition would necessitate a huge and immediate increase in federal debt. Market participants and political interests are likely to fear an impossible strain on the credit market. Perhaps the transition could be staged over time to make it less “shocking”, but that would complicate matters. In any case, heavy debt issuance is the rub that dissuades most observers from supporting privatization.

Fiscal Theory of Price Level

The fiscal theory of the price level (FTPL) implies that such a privatization might not be an insurmountable challenge after all, at least in terms of comparative dynamics. Much background on FTPL can be found at John Cochrane’s Grumpy Economist Substack.

FTPL asserts that fiscal policy can influence the price level due to a constraint on the market value of government debt. This market value must be in balance with the expected stream of future government primary surpluses. This is known as the government budget constraint.

The primary surplus excludes the government’s interest expense, a budget component that must be paid out of the primary surplus or else borrowed. Of course, the market value of government debt incorporates the discounted value of future interest payments.

This budget constraint must be true in an expectational sense. That is, the market must be convinced that future surpluses will be adequate to pay all future obligations associated with the debt. Otherwise, the value of the debt must change.

Should a spending initiative require the government to issue new debt with no credible offset in terms of future surpluses, the market value of the debt must decline. That means interest rates and/or the price level must rise. If interest rates are fixed by the monetary authority (the Fed) then only prices will rise.

A SS Private Option Under FTPL

But what about FTPL in the context of entitlement reform, specifically a privatization of Social Security? Suppose the government issues debt and then deposits the proceeds into personal accounts to fund future benefits. Future government surpluses (deficits) would increase (decrease) by the reduction in future SS benefit payments.

This improved budgetary position should be highly credible to financial markets, despite the fact that benefits are not and never have been guaranteed. If it is credible to markets, the new debt would not raise prices, nor would it be valued differently than existing debt. There need not be any change in interest rates.

But Thin Ice

There are risks, of course. It might be too much to hope that other federal spending can be restrained. That kind of failure would subvert the rationale for any budgetary reform. A variety of other crises and economic shocks are also possible. Those could disrupt markets and jeopardize budget discipline as well. Given a severe shock, interest expense could more readily explode given the massive debt issuance required by the reform discussed here. So there are big risks, but one might ask whether they could turn out to be more disastrous in the absence of reform.

Other Details

The private account “offers” extended to workers or beneficiaries relative to the actuarial PVs of their future benefits would be controversial. Different offer percentages (discounts) could be tested to guage uptake.

Another issue: provisions would have to be made for individuals in “unbanked” households, estimated by the FDIC to be about 4.2% of all U.S. households in 2023. Voluntary uptake of the “offer” is likely to be lower among the unbanked and among those having less confidence in their ability to make financial decisions. However, even a simplified set of choices might be superior to the returns under today’s SS, even for low-income workers, not to mention the very real threat of future reductions in benefits. Furthermore, financial institutions might compete for new accounts in part by offering some level of financial education for new clients.

A similar reform could be applied to Medicare, which like SS is also technically insolvent. Participating beneficiaries could receive some proportion of expected future benefits in a private account, which they could use to pay for private or public health insurance coverage or medical expenses. From a budget perspective, the increase in federal debt would be balanced against the reduction in future Medicare benefits, which would constitute a credible increase (decrease) in future surpluses (deficits).

Credibility

But again, how credible would markets find the decrease in benefit obligations? Direct reductions in future entitlements should be convincing, though politicians are likely to find plenty of other ways to use the savings.

On the other hand, markets already give some weight to the possibility of future benefit cuts (or other policies that would reduce SS shortfalls). So it’s likely that markets will give the reform’s favorable budget implications significant but only “incremental credit”.

Another possible complication is that the market, prior to execution of the reform, might discount the uptake by workers and current retirees. This would necessitate better offers to improve uptake and more debt issuance for a given reduction in future obligations. Skepticism along these lines might worsen implications for the price level and interest rates.

The Trust Fund

Finally, what about the SS Trust Fund? Can it play in role in the reform discussed above? The answer depends on how the trust fund fits into the federal government’s budgetary position.

The trust fund holds as assets only non-marketable Treasury securities acquired in the past when SS contributions exceeded benefit payments. The excess payroll tax revenue was placed in the trust fund, which in turn lent the funds to the federal government to help meet other budgetary needs. Hence the bond holdings.

In terms of the government’s fiscal position, the money has already been pissed away, as it were. The bonds in the trust fund do not represent a pot of money. As noted above, with our age demographics now reversed, payroll taxes no longer meet benefits. Thus, bonds in the trust fund must be redeemed to pay all SS obligations. The Treasury must pay off the bonds via general revenue or by borrowing additional amounts from the public.

Post-reform, if continuing deficits are the order of the day, redeeming bonds in the trust fund would do nothing to improve the government’s fiscal position. If the trust fund “cashes them in” to help meet benefit payments, the federal government must borrow to raise that cash. In other words, the bonds in the trust fund would be more or less superfluous.

But what if the federal budget swings into a surplus position post-reform? In that case, federal tax revenue would cover the redemption of at least some of the bonds held by the trust fund. SS beneficiaries would then have a meaningful claim on federal taxpayers through the trust fund and the government’s surplus position, which would reduce the new federal debt required by the reform.

Conclusion

The Social Security and Medicare systems are in desperate need reform, but there is little momentum for any such undertaking. Meanwhile, exhaustion of the SS and Medicare trust funds creeps ever closer, along with required benefit cuts. All of the reform options would be painful in one way or another. A voluntary privatization would require a huge makeover, but it might be the least painful option of all. Current workers and beneficiaries would not be compelled to make choices they found inferior. Moreover, the new debt necessary to pay for the reforms would be matched by a reduction in future government obligations. The fiscal theory of the price level implies that the reform would not be inflationary and need not depress the value of Treasury bonds, provided the reform is accompanied by long-term budget discipline.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Note: the chart at the top of this post was produced by the Congressional Budget Office and appears in this publication.