Tags

Activist Policy, Argentina, Benchmark Revisions, Charles Manski, Creative Destruction, Double Counting, Fischer Black, Hong Kong, Identification Problem, Interventionism, John von Neumann, Market Monetarism, Measurement Errors, Oskar Morgenstern, Paul Romer, Phlogiston, Policy Uncertainly, Price Aggregates, Real Business Cycle Model, Real GDP, Reuben Brenner, Scott Sumner, Simon Kuznets, Tyler Cowen

As a long-time user of macroeconomic statistics, I admit to longstanding doubts about their accuracy and usefulness for policymaking. Almost any economist would admit to the former, not to mention the many well known conceptual shortcomings in government economic statistics. However, few dare question the use of most macro aggregates in the modeling and discussion of policy actions. One might think conceptual soundness and a reasonable degree of accuracy would be requirements for serious policy deliberation, but uncertainties are almost exclusively couched in terms of future macro developments; they seldom address variances around measures of the present state of affairs. In many respects, we don’t even know where we are, let alone where we’re going!

Early and Latter Day Admonitions

In the first of a pair of articles, Reuven Brenner discusses the hazards of basing policy decisions on economic aggregates, including critiques of these statistics by a few esteemed economists of the past. The most celebrated developer of national income accounting, Simon Kuznets, was clear in expressing his reservations about the continuity of the U.S. National Income and Product Accounts during the transition to a peacetime economy after World War II. The government controlled a large share of economic activity and prices during the war, largely suspending the market mechanism. After the war, market pricing and private decision-making quickly replaced government and military planners. Thus, the national accounts began to reflect values of production inherent in market prices. That didn’t necessarily imply accuracy, however, as the accounts relied (and still do) on survey information and a raft of assumptions.

The point is that the post-war economic results were not remotely comparable to the data from a wartime economy. Comparisons and growth rates over this span are essentially meaningless. As Brenner notes, the same can be said of the period during and after the pandemic in 2020-21. Activity in many sectors completely shut down. In many cases prices were simply not calculable, and yet the government published aggregates throughout as if everything was business as usual.

More than a decade after Kuznets, the game theorists Oskar Morgenstern and John von Neumann both argued that the calculations of economic aggregates are subject to huge degrees of error. They insisted that the government should never publish such data without also providing broad error bands.

Morgenstern delineated several reasons for the inaccuracies inherent in aggregate economic data. These include sampling errors, both private and political incentives to misreport, systematic biases introduced by interview processes, and inherent difficulties in classifying components of production. Also, myriad assumptions must be fed into the calculation of most economic aggregates. A classic example is the thorny imputation of services provided by owner-occupied homes (akin to the value of services generated by rental units to their occupants). More recently. Charles Manski reemphasized Morganstern’s concerns about the aggregates, reaching similar conclusions as to the wisdom of publishing wide ranges of uncertainty.

Real or Unreal?

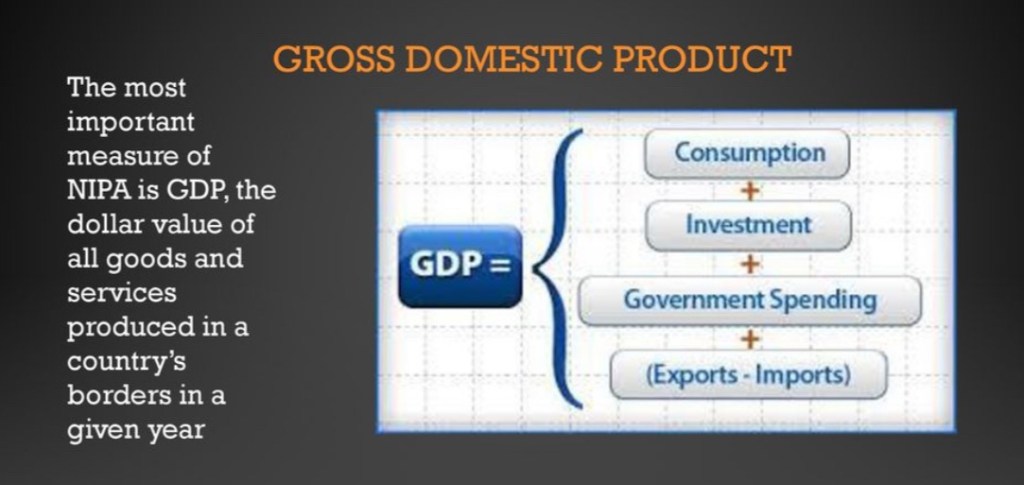

Estimates of real spending and production are subject to even larger errors than estimates of nominal values. The latter are far simpler to measure, to the extent that they represent a simple adding up of current amounts spent (or income earned) over the course of a given time period. In other words, nominal aggregates represent the sum of prices times quantities. To estimate real quantities, nominal values must be adjusted (deflated) by price aggregates, the measurement of which are fraught with difficulties. Spending patterns change dramatically over time as preferences shift; technology advances, new goods and services replace others, and the qualities of goods and services evolve. A “unit of output” today is usually far different than what it was in the past, and adjusting prices for those changes is a notorious challenge.

This difficulty offers a strong rationale for relying on nominal quantities, rather than real quantities, in crafting certain kinds of policy. Perhaps the best example of the former is so-called market monetarism and monetary policy guided by nominal GDP-level targeting, as championed by Scott Sumner.

Government’s Contribution

Another fundamental qualm is the inconsistency between data on government’s contribution to aggregate production versus private sector contributions. This is similar in spirit to Kuznets’ original critique. Private spending is valued at market prices of final output, whereas government spending is often valued at administered prices or at input cost.

An even deeper objection is that much of the value of government output is already subsumed in the value of private production. Kuznets himself thought so! For example, to choose two examples, public infrastructure and law enforcement contribute services which enhance the private sector’s ability to reliably produce and deliver goods to market. To add the government’s “output” of these services separately to the aggregate value of private production is to double count in a very real sense. Even Tyler Cowen is willing to entertain the notion that including defense spending in GDP is double counting. The article to which he links goes further than that.

Nevertheless, our aggregate measures allow for government spending to drive fluctuations in our estimates of GDP growth from one period to another. It’s reasonable to argue that government spending should be reported as a separate measure from private GDP.

But what about the well known Keynesian assertion that an increase in government spending will lift output by some multiple of the change? That proposition is considered valid (by Keynesians) only when resources are idle. Of course, today we see steady growth of government even at full employment, so the government’s effort to commandeer resources creates scarcity that crowds out private activity.

Measurement and Policy Uncertainty

Acting on published estimates of economic aggregates is hazardous for a number of other reasons. Perhaps the most basic is that these aggregates are backward-looking. A policy activist would surely agree that interventions should be crafted in recognition of concurrent data (were it available) or, even better, on the basis of reliable predictions of the future. Financial market prices are probably the best source of such forward-looking information.

In addition, revising the estimates of aggregates and their underlying data is an ongoing process. Initial published estimates are almost always based on incomplete data. Then the estimates can change substantially over subsequent months, underscoring uncertainty about the state of the economy. It is not uncommon to witness consistent biases over time in initial estimates, further undermining the credibility of the effort.

Even worse, substantial annual revisions and so-called “benchmark revisions” are made to aggregates like GDP, inflation, and employment data. Sometimes these revisions alter economic history substantially, such as the occurrence and timing of recessions. All this implies that decisions made on the basis of initial or interim estimates are potentially counterproductive (and on a long enough timeline, every aggregate is an “interim” estimate). At a minimum, the variable nature of revisions, which is an unavoidable aspect of publishing aggregate statistics, magnifies policy uncertainty.

Case Studies?

Brenner cites two historical episodes as support for his argument that aggregates are best ignored by policymakers. They are interesting anecdotes, but he gives few details and they hardly constitute proof of his thesis. In 1961, Hong Kong’s financial secretary stopped publishing all but “the most rudimentary statistics”. Combined with essentially non-interventionist policy including low tax rates, Hong Kong ran off three decades of impressive growth. On the other hand, Argentina’s long economic slide is intended by Brenner to show the downside of relying on economic aggregates and interventionism.

Bad Models, Bad Policy

It’s easy to see that economic aggregates have numerous flaws, rendering them unreliable guides for monetary and fiscal policy. Nevertheless, their publication has tended to encourage the adoption of policy interventions. This points to another issue lurking in the background: the role of economic aggregates in shaping the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the models on which policy recommendations are based. The conceptual difficulties surrounding aggregates, and the errors embedded within measured aggregates, have helped to foster questionable model treatments from a scientific perspective. For example, Paul Romer has said:

“Macroeconomists got comfortable with the idea that fluctuations in macroeconomic aggregates are caused by imaginary shocks, instead of actions that people take, after Kydland and Prescott (1982) launched the real business cycle (RBC) model. … [which] explains recessions as exogenous decreases in phlogiston.”

This is highly reminiscent of a quip by Brenner that macroeconomics has become a bit like astrology. A succession of macro models after the RBC model inherited the dependence on phlogiston. Romer goes on to note that model dependence on “imaginary” forces has aggravated the longstanding problem of statistically identifying individual effects. He also debunks the notion that adding expectations to models helps solve the identification problem. In fact, Romer insists that it makes it worse. He goes on to paint a depressing picture of the state of macroeconomics, one to which its reliance on faulty aggregates has surely contributed.

Aggregates also mask the detailed, real-world impacts of policies that invariably accompany changes in spending and taxes. While a given fiscal policy initiative might appear to be neutral in aggregate terms, it is almost always distortionary. For example, spending and tax programs always entail a redirection of resources, whether a consequence of redistribution, large-scale construction, procurement, or efforts to shape the industrial economy. These are usually accompanied by changes in the structure of incentives, regulatory requirements, and considerable rent seeking activity. Too often, outlays are dedicated to shoring up weak sectors of the economy, short-circuiting the process of creative destruction that serves to foster economic growth. Yet the macro models gloss over all the messy details that can negate the efficacy of activist fiscal policies.

Conclusion

The reliance of macroeconomic policy on aggregates like GDP, employment, and inflation statistics certainly has its dangers. These measures all suffer from theoretical problems, and they simply cannot be calculated without errors. They are backward-looking, and the necessity of making ongoing revisions leads to greater uncertainty. But compared to what? There are ways of shifting the focus to measures subject to less uncertainty, such as nominal income rather than real income. A number of theorists have proposed market-based methods of guiding policy, including Fischer Black. This deserves broader discussion.

The problems of aggregates are not solely confined to measurement. For example, national income accounting, along with the Keynesian focus on “underconsumption” during recessions, led to the fallacious view that spending decisions drive the economy. This became macroeconomic orthodoxy, driving macro mismanagement for decades and leading to inexorable growth in the dominance of government. Furthermore, macroeconomic models themselves have been corrupted by the effort to explain away impossibly error-prone measurements of aggregate activity.

Brenner has a point: it might be more productive to ignore the economic aggregates and institute stable policies which reinforce the efficacy of private markets in allocating resources. If nothing else, it makes sense to feature the government and private components separately.