Tags

Antitrust, Greed, Ham Sandwich Nation, Hoarding, Inflation, Interventionism, Kamala Harris, Mark-Ups, Market Concentration, Markets, Michael Munger, Monetary policy, Predatory Pricing, Price Fixing, Price Gouging, Price Rationing, Shortages, Supply Shocks

Economic ignorance and campaign politics seem to go hand-in-hand, especially when it comes to the rhetoric of avowed interventionists. They love “easy” answers. If they get their way, negative but predictable consequences are always “unintended” and/or someone else’s fault. Unfortunately, too many journalists and voters like “easy” answers, and they repeatedly fall for the ploy.

This post highlights one of many bad ideas coming out of the Kamala Harris campaign. I probably won’t have time to cover all of her bad ideas before the election. There are just too many! I hope to highlight a few from the Trump campaign as well. Unfortunately, the two candidates have more than one bad idea in common.

Price Gouging

Here I’ll focus on Harris’ destructive proposal for a federal ban on “price gouging”. Unfortunately, she has yet to define precisely what she means by that term. On its face, she’d apparently support legislation authorizing the DOJ to go after grocers, gas stations, or other sellers in visible industries charging prices deemed excessive by the federal bureaucracy. This is a form of price control and well in keeping with the interventionist mindset.

As Michael Munger has said, when you charge “too much” you are “gouging”; when you charge “too little” you are “predatory”; and when you charge the same price as competitors you’ve engaged in a price fixing conspiracy. The fact that Harris’ proposal is deliberately vague is an even more dangerous invitation to arbitrary caprice by federal enforcers. It might be hard to price a ham sandwich without breaking such a law.

The great advantage of the price system is its impersonal coordination of the actions of disparate agents, creating incentives for both buyers and sellers to direct resources toward their most valued uses. Price controls of any kind short circuit that coordination, inevitably leading to shortages (or surpluses), misallocations, and diminished well being.

Inflation As Aggregate Macro Gouging

Aside from vote buying, Harris has broader objectives than the usual “anti-gouging” sentiment that accompanies negative supply shocks. She’s faced mounting pressure to address prices that have soared during the Biden Administration. The inflation during and after the COVID pandemic was induced by supply shortfalls first and then a spending/money-printing binge by the federal government. The pandemic induced shortages in some key areas, but the Treasury and the Fed together engineered a gigantic cash dump to accommodate that shock. This stimulated demand and turned temporary dislocations into permanently higher prices.

There were howls from the Left that greed in the private sector was to blame, despite plentiful evidence to the contrary. Blaming “price gouging” for inflated prices dovetails with Harris’ proclivity to inveigh against “corporate greed”. It’s typical leftist blather intended to appeal to anyone harboring suspicions of private property and the profit motive.

The profit motive is a compelling force for social good, motivating the performance of large corporations and small businesses alike. Diatribes against “greed” coming from the likes of a career politician with no private sector experience are not only unconvincing. They reveal childlike misapprehensions regarding economic phenomena.

More substantively, some have noted that mark-ups rose during and after the pandemic, but these markups are explained by normal cyclical fluctuations and the growing dominance of services in the spending mix. High margins are difficult to sustain without persistently high levels of demand. The Fed’s shift toward monetary restraint has dissipated much of that excessive demand pressure, but certainly not enough to bring prices back to pre-pandemic levels, which would require a severe economic contraction.

Claims that concentration among sellers has risen in some markets are also cited as evidence that greedy, price-gouging corporations are fueling inflation. If that is a real concern, then we might expect Harris to lean more heavily on antitrust policy. She should be circumspect in that regard: antitrust enforcement is too often used for terrible reasons (and also see here). In any case, rising market concentration does not necessarily imply a reduction in competitive pressures. Indeed, it might reflect the successful efforts of a strong competitor to please customers, delivering better value via quality and price. Moreover, mergers and acquisitions often result in stronger challenges to dominant players, energizing innovation, improved quality, and price competition.

If Harris is serious about minimizing inflation she should advocate for fiscal and monetary restraint. We’ve heard nothing of that from her campaign, however. No credible plans other than vaguely-defined price controls and promises to tax and spend our way to a joyful “opportunity economy”.

Disaster Supply Gouging

There is already a federal law against hoarding “scarce items” in times of war or national crisis and reselling at more than the (undefined) “prevailing market price”. There are also laws in 34 states with varying “anti-gouging” provisions, mostly applicable during emergencies only. These laws are counterproductive as they tend to “gouge” the flow of supplies.

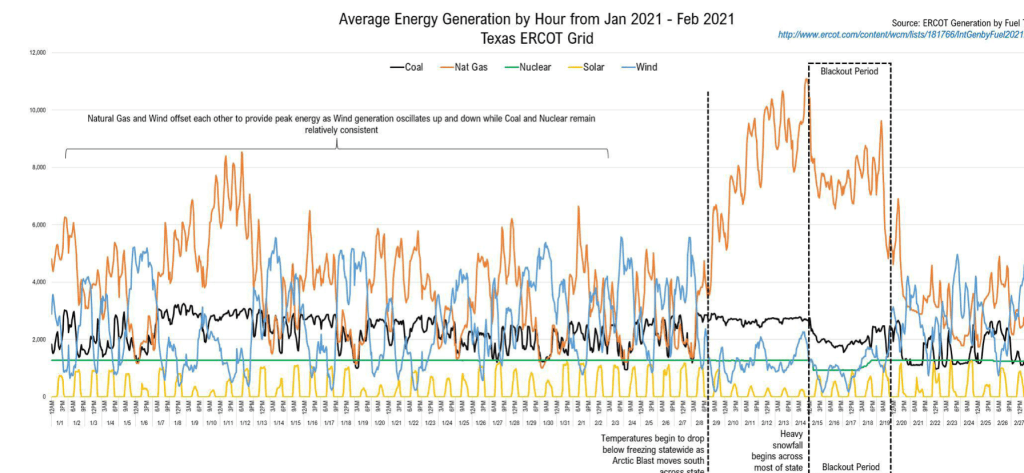

In the aftermath of terrible storms or earthquakes, there are almost always shortages of critical goods like food, water, and fuel, not to mention specialized manpower, machinery, and materials needed for cleanup and restoration. As I pointed out some time ago, retailers often fail to adjust their prices under these circumstances, even as shelves are rapidly emptied. They are sometimes prohibited from repricing aggressively. If not, they are conflicted by the predictable hoarding that empties shelves, the higher costs of replenishing inventory, and the knowledge that price rationing creates undeservedly bad public relations. So retailers typically act with restraint to avoid any hint of “gouging” during crises.

Disasters often disrupt production and create physical barriers that hinder the very movement of goods. When prices are flexible and can respond to scarcity on the ground, suppliers can be very creative in finding ways to deliver badly needed supplies, despite the high costs those are likely to entail. Private sellers can do all this more nimbly and with greater efficiency than government, but they need price incentives to cover the costs and various risks. Price controls prevent that from happening, prolonging shortages at the worst possible time.

The chief complaint of those who oppose this natural corrective mechanism is that higher prices are “unfair”. And it is true that some cannot afford to pay higher prices induced by severe scarcity. The answer here is that government can write checks or even distribute cash, much as the government did nationwide during the pandemic. That’s about the only thing at which the state excels. Then people can afford to pay prices that reflect true levels of scarcity. If done selectively and confined to a regional level, the broader inflationary consequences are easily neutralized.

Instead, the knee-jerk reaction is to short-circuit the price mechanism and insist that available supplies be rationed equally. That might be a fine way for retailers to respond in the short run. Share the misery and prevent hoarding. But supplies will run low. When the shelves are empty, the price is infinite! That’s why sellers must have flexibility, not prohibitions.

Blame Game

Harris is engaged in a facile blame game at both the macro and micro level. She claims that inflation could be controlled if only corporations weren’t so greedy. Forget that they must cover their own rising costs, including the costs of compensating risk-averse investors. For that matter, she probably hasn’t gathered that a return to capital is a legitimate cost. Like many others, Harris seems ignorant of the elevated costs of bringing goods to market following either unpredictable disasters or during a general inflation. She also lacks any understanding of the benefits of relying on unfettered markets to bridge short-term gaps in supply. But none of this is surprising. She follows in a long tradition of ignorant interventionism. Let’s hope we have enough voters who aren’t that gullible.