Tags

Amazon, Beige Book, Capitalism, Chad Wolf, Consumer Sovereignty, Costco, Eating Tariffs, Free Markets, Import Competing Goods, Mussolini, New Right, Price Gouging, Profit Motive, Protectiinism, Retail Margins, Target, Tariffs, Tax Incidence, WalMart

An opinion piece caught my eye written by one Chad Wolf. It’s entitled: “Retailers caught red-handed using Trump’s tariffs as cover for price gouging”. A good rule is to approach allegations of “price gouging” with a strong suspicion of economic buffoonery. You tend to hear such gripes just when prices should rise to discourage over-consumption and encourage production. The Wolf article, however, typifies the kind of attack on capitalism we hear increasingly from the “new right” (and see this).

Wolf, a former Homeland Security official in the first Trump Administration, says that large retailers like Walmart and Target are ripping off American consumers by raising prices on goods that are, in his judgement, “unaffected” by tariffs.

We’ll get into that, but first a quick disclaimer: I have no connection to Walmart or Target. Sure, I’ve shopped at those stores and I’ve filled a few prescriptions at a Walmart pharmacy. Maybe I have an ETF with an interest, but I have no idea.

Competition and Consumer Choice

Of course, no one forces consumers to shop at Walmart or Target. Those stores compete with a wide variety of outlets, including Costco and Amazon, the latter just a few clicks away. In a market, sellers price goods at what the market will bear, which ultimately serves to signal scarcity: a balancing between the cost of required resources and the value assigned by buyers. Unfortunately, in the case of tariffs, buyers and sellers of imports must deal with an artificial form of scarcity designed to extract revenue while benefitting other interests.

Wolf touts the “gift” of a free market for American businesses, as if private rights flow from government beneficence. He then decries a so-called betrayal by large retailers who would “price gouge” the American consumer in an effort to protect their profit margins. The free market is indeed a great thing! But his indignance is highly ironic as a pretext for defending tariffs and protectionism, given their destructive effect on the free operation of markets.

Broader Impacts

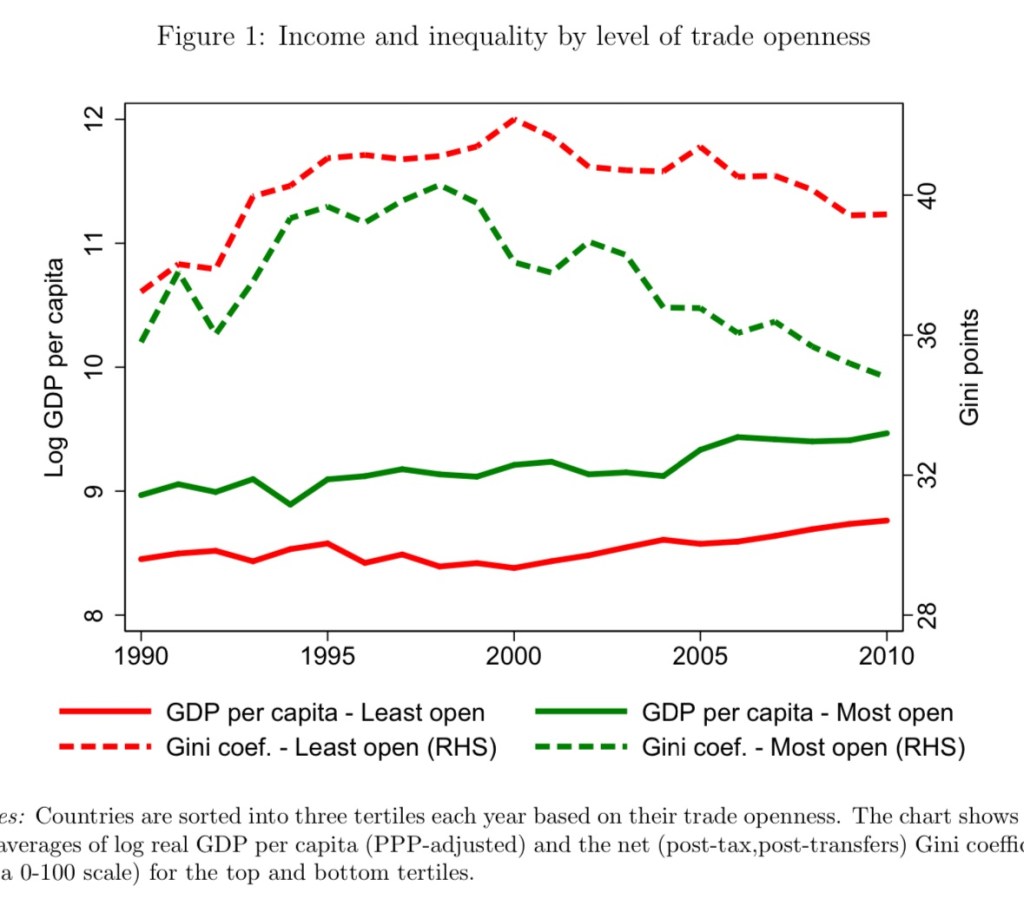

Wolf might be unaware that tariffs have an impact on a large number of domestically-produced goods that are not imported, but nevertheless compete with imports. When a tariff is charged to buyers of imports, producers of domestic substitutes experience greater demand for their products. That means the prices of these import-competing goods must rise. Furthermore, the effect can manifest even before tariffs go into effect, as consumers begin to seek out substitutes and as producers anticipate higher input costs.

Obviously, tariffs also impinge on producers who rely on imports as inputs to production. It’s not clear that Wolf understands how much tariffs, which represent a direct increase in costs, hurt these firms and their competitive positions.

“Expected” Does Not Mean “Unaffected”

Wolf cites the Federal Reserve’s Beige Book report (which he calls a “study”) to support his claim that businesses are gouging buyers for goods “unaffected” by tariffs. Here is one quote he employs:

“A heavy construction equipment supplier said they raised prices on goods unaffected by tariffs to enjoy the extra margin before tariffs increased their costs,” the Beige Book report said.“

Read that again carefully! Apparently Wolf, and whoever added this to the Fed’s Beige Book, thinks that being “unaffected by tariffs” includes firms whose future costs, including replacement of inventories, will be affected by tariffs! He goes on to say:

“… Walmart has already issued price hikes under the guise of tariff costs.“

The examples at his “price hikes” link were for Chinese goods in April and May, after Trump announced 145% tariffs on China in April. In mid-May, Trump said China would face a lower 30% tariff rate during a 90-day “pause” while a trade agreement was negotiated. It is now 55%, but the point is that retailers were forced to play a guessing game with respect to inventory replacement costs due to uncertainty imposed by Trump. They had a sound reason for marking up those items.

Fibbing on the Margin

Here’s an excerpt from Wolf’s diatribe that demonstrates his cluelessness even more convincingly:

“We all know many of these large retailers are sitting on comfortable, even expanded, profit margins because of the price hikes from COVID-19 that never came down. But it’s not enough for them. They want to fleece the American consumer and blame it on President Trump’s America First agenda.“

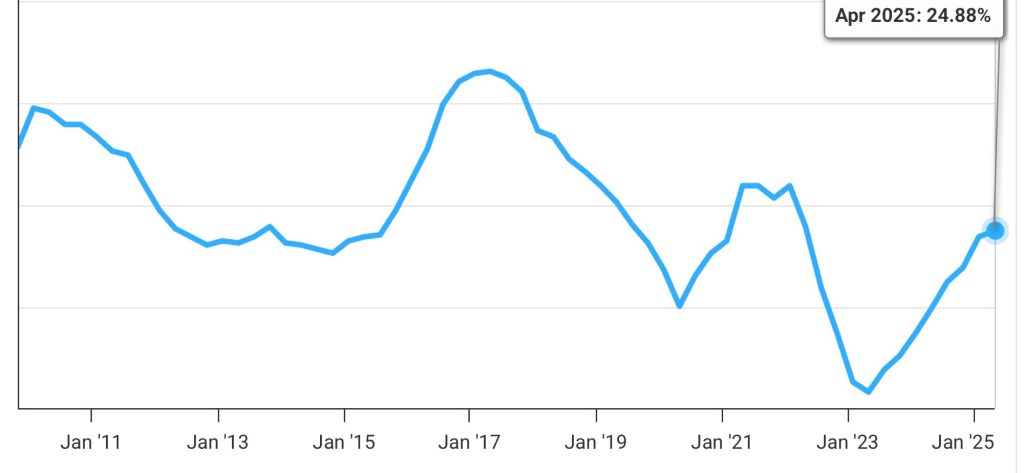

So let’s take a look at those profit margins that “never came down” after the pandemic, but in a longer historical context. Here are gross margins for Walmart since 2010:

Walmart’s margin today is about the same as the average for discount stores, and it is lower than for department stores, retailers of household and personal products, groceries, and footwear. Furthermore, it is lower today than it was ten years ago. While the margin increased a little during the pandemic, it fell in its aftermath, contrary to Wolf’s assertion. That the company has rebuilt margins steadily since 2023 should be viewed not as an indictment, but perhaps as a testament to improved managerial performance.

Wolf goes on to quote a former Walmart CEO who says that the 25 basis point increase in the gross margin in the latest quarter (from ~24.7% to 24.94%) indicates that the chain can “manage” the tariff impact. Of course it can, but that would not constitute “price gouging”.

A Trump Lackey

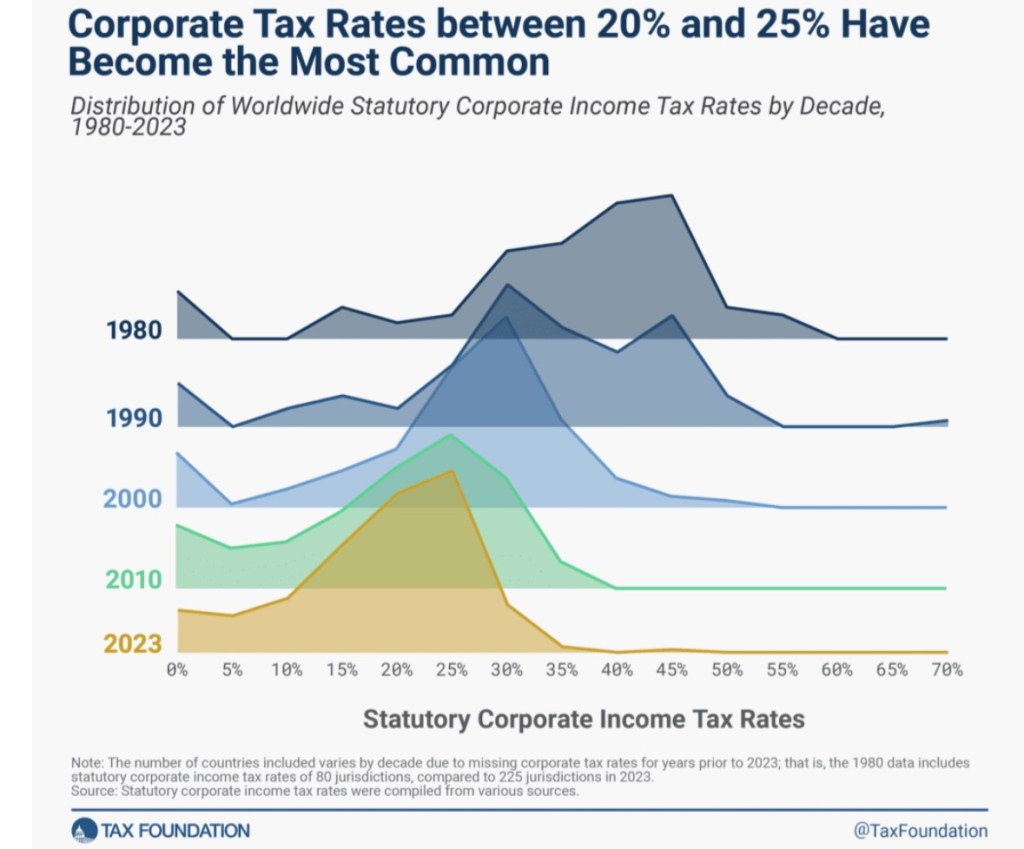

Of course, Wolf is taking his cues from Donald Trump, who has been bullying American businesses to “eat” the cost of his tariff onslaught, rather than passing them along to the ultimate buyers of imported goods. However, private businesses should not be expected to take orders from the President. This is not Mussolini’s Italy. Moreover, anyone familiar with tax incidence will understand that sellers are likely to eat some portion of a tariff (sharing the burden with buyers) without jawboning from the executive branch. That’s because buyers demand less at higher prices and sellers wish to avoid losing profitable sales, to the extent they can. But the dynamics of this adjustment process might take time to play out.

It’s also worth noting that a retailer might attempt to hold the line on certain prices in an uncertain cost environment. This uncertainty is a real cost inflicted by Trump. Meanwhile, pointing to increased prices for domestic goods, even if they are truly unaffected by tariffs, proves nothing without knowledge of the relevant cost and market conditions for those goods. It certainly doesn’t prove an “unpatriotic” attempt to cross subsidize imported goods.

In fact, one might say it’s unpatriotic for the federal government to restrict the market choices faced by American consumers and businesses, and for the President to tell American sellers that they better “eat” the cost of tariffs (or else?). And say, what happened to the contention that tariffs aren’t taxes?

Conclusion

Attacks on sellers attempting to recoup tariff costs are unfair and anti-capitalist. They are also somewhat disdainful of the economic sovereignty of American consumers, though not as much as the tariffs themselves. In the case described above, Chad Wolf would have us believe that sellers should not act on their expectations of near-term tariff increases. He also fails to recognize the impact of tariffs on import-competing goods and the cost of tariffs borne by producers who must rely on imported goods as inputs to production. Even worse, Wolf misrepresents some of the evidence he uses to make his case.

More generally, American businesses should not be bullied into taking a hit just because they serve customers who wish to buy imported goods. There is nothing unpatriotic about the freedom to choose what to goods to buy, what goods to stock, and how to maintain profitability in the face of government interference.