Tags

Alex Tabarrok, Billionaire Tax, Capital Flight, Jason Furman, Joe Biden, Kamala Harris, Michael Munger, Moore v. United States, Notional Equity Interest, Sam Altman, Tyler Cowen, ULTRA, Unrealized Capital Gains, Wealth Tax

Kamala Harris’ campaign platform lifts several tax provisions from Joe Biden’s ill-fated campaign. The most pernicious of these are lauded by observers on the Left for their “fairness”, but they dismiss some rather obvious economic damage these provisions would inflict. Here, I’ll cover Harris’ proposal to tax unrealized capital gains of the rich in two different ways:

- A minimum 25% “billionaire tax” on the “incomes” of taxpayers with net worth exceeding $100 million. This definition of income would include unrealized capital gains.

- A tax of 28% at the time of death on unrealized capital gains in excess of $5 million ($10 million for joint returns).

Why Bother?

To get a whiff of the complexity involved, take a look at the description on pp. 79 – 85 of this document, to which the Harris proposal seems to correspond. It’s not fully fleshed out, but it’s easy to imagine the lucrative opportunities this would create for tax attorneys and accountants, to say nothing of job openings at the IRS!

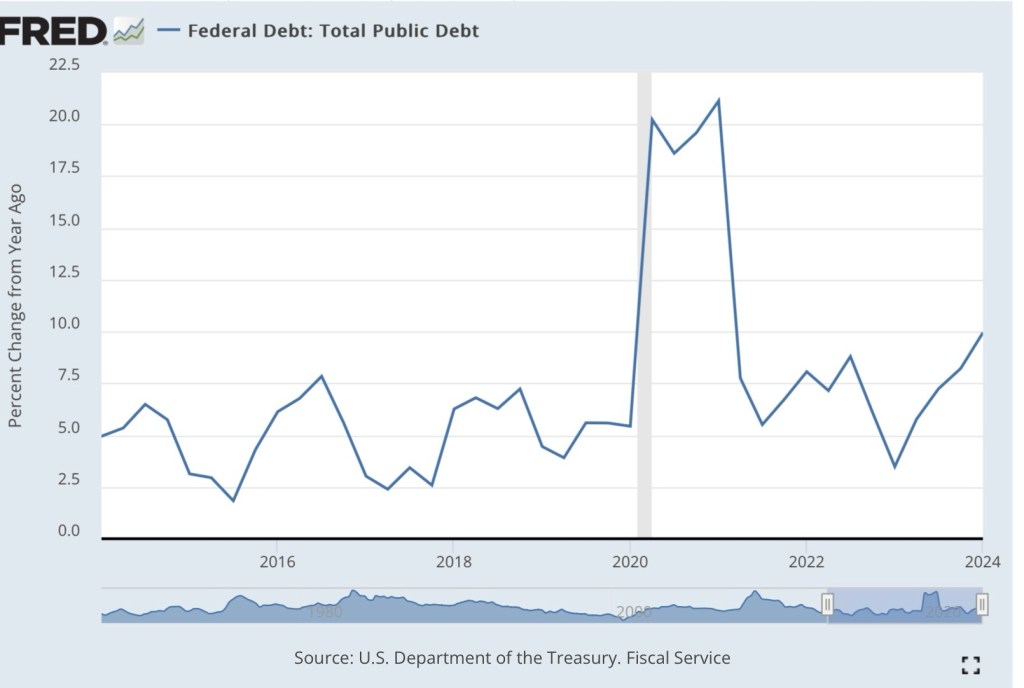

On the other hand, there’s little chance these proposals would be approved by Congress, no matter which party holds a majority. Harris knows that, or at least her advisors do. That taxation of unrealized gains is even part of the conversation in a presidential election year tells us how normalized the idea has become within the Democrat Party, which seems to have lost all regard for private property rights. These are classist proposals designed to garner the votes of the “tax-the-rich” crowd, who either aren’t aware or haven’t come to grips with the fact that the U.S. already has a very progressive income tax system. “The rich” already pay a disproportionately high share of taxes.

Taxable Income

These provisions would complicate and corrupt the income tax code by distorting the definition of income for tax purposes. The Internal Revenue Code has always been consistent in defining taxable income as realized income. One might use the expression “mark-to-market taxation” to characterize a tax on unrealized gains from tradable assets. It’s much more difficult to estimate unrealized gains on non-tradable or infrequently traded investments, for which there is no ready market value.

There is one type of income that some believe to be taxed as unrealized. A few weeks ago, in a post about Sam Altman’s infatuation with a wealth tax, I cited a recent Supreme Court decision that has been mistakenly interpreted as favoring income taxation of unrealized gains or a wealth tax. In fact, Moore v. United States involved the undistributed profits of a foreign pass-through entity (i.e., not a C corporation) for purposes of the mandatory repatriation tax. The foreign firm’s profits were realized, and its pass-through status meant that the U.S. owners had also, by definition, realized the profits. So this case did not set a precedent or create an exception to the rule that income taxation applies only to realized income.

Forced Sales

Tradable assets with easily recorded market values will often have unrealized gains in a given year. While tax payments might be spread over the current and future tax years, these taxes could necessitate asset sales to pay the taxes owed. If unrealized losses are treated symmetrically, they would require either future deductions or possibly credits for prior tax payments.

Estimates of unrealized gains on illiquid or private investments like closely-held business interests, artwork, or real estate are highly uncertain and subject to dispute. A large tax liability on such an asset could be especially burdensome. Cash must be raised, which might require a forced sale of other assets. And again, these valuations often come with great complexity and exorbitant administrative costs, not just for the IRS, but especially for taxpayers.

Economic Downsides

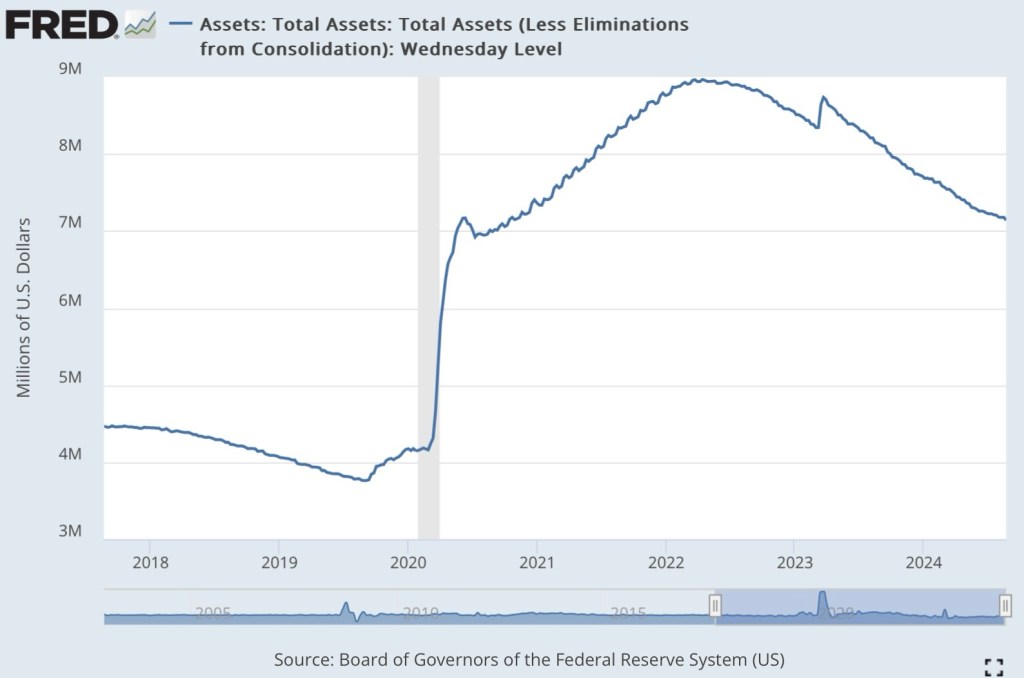

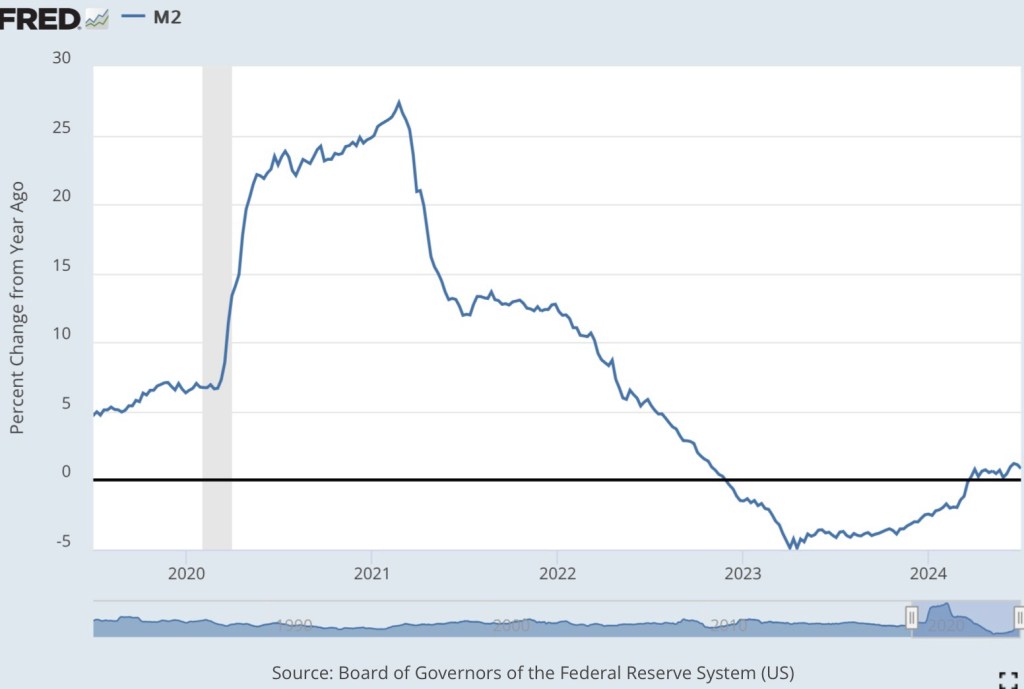

As I noted above, additional taxes on unrealized gains would create an obvious need for liquidity, if not immediately then at death. With or without careful planning, sales of assets by wealthy investors to pay the tax would undermine market values of equity (and other assets), producing a broader loss of wealth economy-wide.

Avoidance schemes would be heavily utilized. For example, a wealthy investor could borrow heavily against assets so as to offset unrealized gains with deductible debt-service costs.

Capital flight is likely to be intense if a Harris tax regime began to take shape in Congress. This might be the best avoidance scheme of all. The U.S. is likely to experience massive capital outflows. Furthermore, investment in new physical capital will decline, ultimately leading to lower productivity and real wages.

Entrepreneurial activity would also take a hit. In a critique of Jason Furman’s effort to justify Harris’ proposal, Tyler Cowen asks why we should be so eager to “whack” venture capital. He also quotes an email from Alex Tabarrok on the detrimental policy effects on rapidly growing start-ups:

“What’s really going on is that you are divorcing the entrepreneur from their capital at precisely the moment that the team is likely most productive. Separation of capital from entrepreneur could negatively impact the company’s growth or the entrepreneur’s ability to manage effectively. The entrepreneur could lose control, for example. If you wait until the entrepreneur realizes the gain that’s the time that the entrepreneur wants out and is ready to consume so it’s closer to taxing consumption and better timed in the entrepreneurial growth process.“

Or the entrepreneur might just decide that a startup would be more rewarding in a tax-friendly environment, perhaps somewhere overseas.

Interest Rates and Tax Receipts

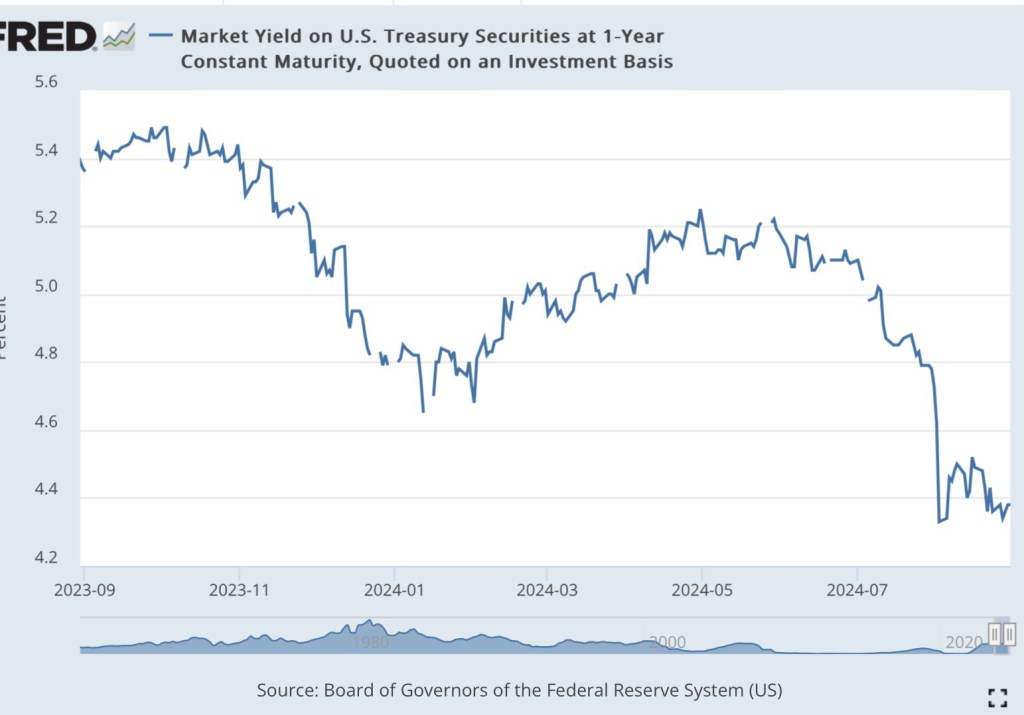

Tabarrok notes in a separate post that much of the variation in stock prices is caused by changes in interest rates. Investors use market rates to determine discount rates at which a firm’s future cash flows can be valued. Thus, changes in rates engender changes in stock prices, capital gains, and capital losses.

A decline in interest rates can raise market valuations without any change in dividends. However, a long-term investor would see no change in pre-tax income or consumption, so the tax could force a series of premature sales. A change in a firm’s expected growth rate would also create an unrealized gain (or loss), but the tax would undermine U.S. equity values. Taxing an actual increase in the dividend is one thing, but taxing a change in expectations of future dividends is another. As Tabarrok puts it, “It’s taxing the chickens before the eggs have hatched.“

Dangerous Narrative, Dangerous Policy

A final objection to taxing unrealized capital gains is that it would cross the line into a form of wealth taxation. Assets come in many forms, but the only time realized values can be discerned are when they are traded. That goes for collectibles, homes, boats, and the full array of financial assets. A corollary is that a very large percentage of wealth is unrealized.

A tax on unrealized gains would be the proverbial camel’s nose under the tent and another incursion into the private realm. So often in the history of taxation we’ve seen narrow taxes expand into broad taxes. This is one more opportunity for the state to extend its dominance and control.

I’ve written in the past about the economic dangers of a wealth tax. First, every dollar of income used to purchase capital is already taxed once. In that sense, the cost basis of wealth would be double taxed under a wealth tax. Second, the supply of capital is highly elastic. This implies a high propensity for capital flight, shallowing of productive physical capital, and reduced productivity and real wages. Avoidance schemes would rapidly be put into play. Given these limitations, the revenue raising potential of a wealth tax is unlikely to live up to expectations. Finally, a wealth tax is unconstitutional, but that won’t stop the Left from pushing for one, especially if they first get a tax on unrealized gains. Even if they are unsuccessful now, the conversation tends to normalize the idea of a wealth tax among low-information voters, and that is a shame.