The other day, a few colleagues were lamenting the incipient robot domination of the workplace. It is true that advances in automation and robotics are likely to displace workers in a variety of fields over the next few decades. However, the substitution of capital for labor is not a new phenomenon. It’s been happening since the start of the industrial age. At the same time, capital has been augmenting labor, making it more productive and freeing it up for higher-valued uses, many of which were previously unimagined. The large-scale addition of capital to the production process has succeeded in raising labor productivity dramatically, and labor income has soared as a consequence. That is likely to continue as increasingly sophisticated robots assume certain tasks entirely and collaborate with workers on others, even in the service sector.

Advanced forms of automation are another step in the progression of technology. The process itself, however, and the adoption of robotics, might well be hastened by public policy that pushes labor costs to levels not commensurate with productivity. I wrote about this process in “Automate No Job Before Its Time” on Sacred Cow Chips late last year. The point of that essay was that government-imposed wage floors create an incentive for automation. Because a wage floor has its impact at the bottom of the wage scale, at which workers are the least-skilled, this form of government intervention creates a regrettable and unnatural acceleration in the automation process. Other mandated benefits and workplace regulations can have similar effects.

Robert Samuelson makes the same points in “Our Robot Panic Is Overblown“. He notes the effectiveness of the U.S. economy in creating jobs over time in the presence of increasing capital-intensity. But he also warns of potential missteps, including the dangers of government activism:

“There are two dangers for the future. One is that the new jobs created by new technologies will require knowledge and skills that are in short supply, leaving unskilled workers without income and the economy with skill scarcities. … The second danger is that government will damage or destroy the job creation process. We live in a profit-making economic system. Government’s main role is to maintain the conditions that make hiring profitable. … If we make it too costly for private firms to hire (through high minimum wages, mandated costs and expensive regulations) — or too difficult to fire — guess what? They won’t hire. That’s what ought to worry us, not the specter of more robots.“

Historically, automation has actually created more jobs than it has destroyed. In general, however, the new jobs have required higher levels of skills than the jobs lost. In “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation“, David Autor of MIT says it this way:

“Automation does indeed substitute for labor—as it is typically intended to do. However, automation also complements labor, raises output in ways that lead to higher demand for labor, and interacts with adjustments in labor supply. … journalists and even expert commentators tend to overstate the extent of machine substitution for human labor and ignore the strong complementarities between automation and labor that increase productivity, raise earnings, and augment demand for labor.“

As with almost all automation, robots will replace workers in the most routine tasks. Tasks involving less routine will not be as readily assumed by robots. To a large degree, people misunderstand the nature of automation in the workplace. The introduction of robots often requires collaboration with humans, but again, these humans must have more highly-developed skills than a typical line worker.

Hal Varian, who is the chief economist at Google, describes the positive implications of the ongoing trend to automate (see the link in the last paragraph of this post), namely, less drudgery and more leisure:

“If ‘displace more jobs’ means ‘eliminate dull, repetitive, and unpleasant work,’ the answer would be yes. How unhappy are you that your dishwasher has replaced washing dishes by hand, or your vacuum cleaner has replaced hand cleaning? My guess is this ‘job displacement’ has been very welcome, as will the ‘job displacement’ that will occur over the next 10 years. The work week has fallen from 70 hours a week to about 37 hours now, and I expect that it will continue to fall. This is a good thing. Everyone wants more jobs and less work. Robots of various forms will result in less work, but the conventional work week will decrease, so there will be the same number of jobs (adjusted for demographics, of course).“

An extreme version of the “robot domination” narrative is that one day in the not-too-distant future, human labor will be obsolete. Automation is not limited to repetitive or menial tasks by any means. A wide variety of jobs requiring advanced skills have the potential to be automated. Already, robots are performing certain tasks formerly done only by the likes of attorneys, surgeons, and computer programmers. Robots have the potential to repair each other, to self-replicate, to solve high-order analytical problems and to engage in self-improvement. With advances in artificial intelligence (AI), might humans one day become wholly obsolete for productive tasks? What does that portend for the future of so many human beings and their dependents who, heretofore, have relied only on their labor to earn a living?

There are any number of paths along which the evolution of technology, and its relationship to workers and consumers, might play out. The following paragraphs examine some of the details:

The Human Touch: There will probably always be consumers who prefer to transact with humans, as opposed machines. This might be limited to a subsegment of the population, and it might be limited to the manufacture of certain artisan goods, such as hand-rolled cigars, or certain services. Some of these services might require qualities that are more uniquely human, such as empathy, and the knowledge that one is dealing with a human would be paramount. This niche market might be willing to pay premium prices, much as consumers of organic foods are willing to pay an extra margin. However, it will be necessary to retain the perceived quality of the human touch and to remain reasonably competitive with automated alternatives on price.

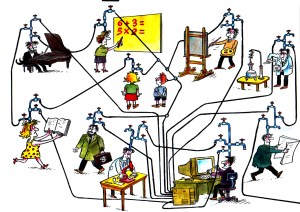

Human Augmentation: Another path for the development of technology is the cyborgization of labor. This might seem rather distasteful to current sensibilities, but it’s a change that is probably inevitable. At least some will choose it. Here is an interesting definition offered by geir.org:

“Cyborgization is the enhancement of a biological being with mechanical or non-genetically delivered biological devices or capabilities. It includes organ or limb replacements, internal electronics, advanced nanomachines, and enhanced or additional capabilities, limbs, or senses.“

These types of modifications can make “enhanced” humans competitive with machines in all kinds of tasks. The development of these kinds of technologies is taking place within the context of rehabilitative medical care and even military technology, such as powerful exoskeletons, but the advances will make their way into normal civilian life. There is also development activity taking place among extreme hobbyists underground, such as “biohackers” who perform self-experimentation, embedding magnets or electronic chips in their bodies in attempts to develop a “sixth sense” or enhanced physical abilities. Even these informal efforts, while potentially risky to the biohackers themselves, might lead to changes that will benefit mankind, much like the many great garage tinkerers who have been important to innovation in the past.

Owning Machines: Ownership of capital will take on a greater role in providing for lifetime earnings. Can the distribution of capital ever be broadened to the extent needed to replace lost labor income? There are ways in which this can occur. The first thing to note is that the transition to a labor-free economy, were that to transpire, would play out over many years. Second, we have witnessed an impressive diffusion of advanced technologies in recent decades. Today, consumers across the income spectrum hold computers in their pockets that are more than the equivalent of the supercomputers that existed 50 years ago. Today’s little computers are far more useful in many ways, given wireless internet connectivity. There are many individuals for whom these devices are integral to earning an income. Thus, the rate of return on these machines can be quite impressive. The same is true of computers, software (sometimes viewed as capital) and printers, not to mention other “modern” contrivances with income-earning potential such as cars, trucks and a vast array of other tools and hardware. Machines with productive potential will continue to make their way into our lives, both as consumers and as individual producers. This also will include value-added production of goods at home, even for use or consumption within the household (think 3D printers, or backyard “farmbots”).

Saving Constructs: Most of the examples above involve machines that require some degree of human collaboration. Of course, even the act of consuming involves labor: I must lift the fork to my mouth for every bite! But in terms of earning income from machines, are there other ways in which ownership of capital can be broadened? The first answer is an old one: saving! But there is no way most individuals at the start of their “careers” can garner a significant share of income from capital. Other social arrangements are probably necessary. One of great importance is the family and family continuity. Many who have contemplated a zero-labor future imagine a world in which there are only two kinds of actors: individuals and the state. Stable families, however, hold the potential for accumulating capital over time to provide a flow of income for their members. Other forms of social organization can fill this role, but they must be able to accumulate capital endowments across generations. Of course, in an imagined world with minimal opportunities for labor, some have concluded that society must collectively provide a guaranteed income. To indulge that view for just a moment, a world of complete automation would almost certainly be a world of superabundance, so goods would be extremely cheap. That means a safety net could be provided at a very low cost. Nonetheless, it would be far preferable to do so by distributing a minimal number of shares of ownership in machines. These shares would have some value, and to improve resource allocation, it should be the individual’s responsibility to manage those shares.

Economic Transition: The dynamics of the transition to robot-dominated production raise some interesting economic questions. Should the advancement of robotics and artificial intelligence create a massive substitution away from labor, it will be spurred by 1) massive upward shifts in the productivity of capital relative to its cost; and 2) real wages that exceed labor’s marginal productivity. There will be stages of surging demand for the kinds of advanced labor skills that are complementary to robots. The demand for less advanced labor services does not have to fall to zero, however. There will be new opportunities that cannot be predicted today. Bidding for scarce capital resources and the flow of available saving will drive up capital costs, slowing the transition. And as long as materials, energy and replacement parts have a cost, and as long as savers demand a positive real return, there will be a margin along which it will be profitable to employ various forms of labor. But downward adjustment of real wages will be required. Government wage-floor policies must be abandoned. That will not be as difficult as it might sound: the kind of automation envisioned here would have profound effects on overall costs and the supply of goods, leading to deflation in the prices of consumables. As long as real factor prices can adjust, there will almost certainly remain a balance between the amounts of capital and labor employed.

In “Robots Are Nothing New“, Don Boudreaux passes along this comment from George Selgin:

“I’ve always been aghast at finding many otherwise intelligent economists arguing as if technology had a mind of its own, developing willy-nilly, or even perversely, in relation to the relative scarcity of available factors, including labor. Only thus can it happen that labor-saving technology develops to a point where labor, instead of being relatively scarce, becomes superabundant!

The fundamental problem, I believe, is confusion of the role of technological change with that of government interference with the pricing of labor services that is among the things to which technology in turn responds. Labor-saving technology becomes associated with unemployment, not because the last is a consequence of the former, but because both are contemporaneous consequences of a common cause, to wit: minimum wage laws and other such interference that sets wage rates above their market-clearing levels.“

There is much disagreement on the implications of automation. This excellent survey of experts by the Pew Research Center contains a number of insights. Also, visit Singularity Hub for a number of great articles on automation and AI, some of which are surprising. I believe that these technologies hold a great deal of promise for humanity. The process will not take place as suddenly as some fear, but ill-conceived policies such as a mandated “living wage” would put us on an unnaturally speedy trajectory. Opportunities for the least-skilled workers will be foreclosed too soon, before those individuals can develop skills and improve their odds of establishing a life free of dependency. Too rapid an adoption of advanced automation and AI would increase the likelihood of choosing suboptimal production methods that might be difficult to change later, and it would leave little time for education and training for workers who might otherwise leverage new technologies. The benefits of automation and their diffusion can be maximized by allowing advances to take a natural course, guided by market forces, with as little interference from government as possible.