Tags

Bidenomics, Cleveland Fed, Inflation Expectations, Joe Biden, Kevin Erdman, Monetary Aggregates, Neutral Fed Funds Rate, Real Interest Rates, Restrictive Policy, TIPS

Note: I’m moving for the first time in many years. We have a lot to do quickly because we’ll close on our new home in early September. It’s in a place with palm trees, but no basements! The clean-up and winnowing of our accumulated papers, possessions, and … junk — not to mention attending to all the details of the move — is taking up all of my time. Anyway, I started the post below a week ago and had to put it aside. Not sure how frequently I’ll be posting till we’re fully settled in the fall, but we’ll see how it goes.

____________________________________________

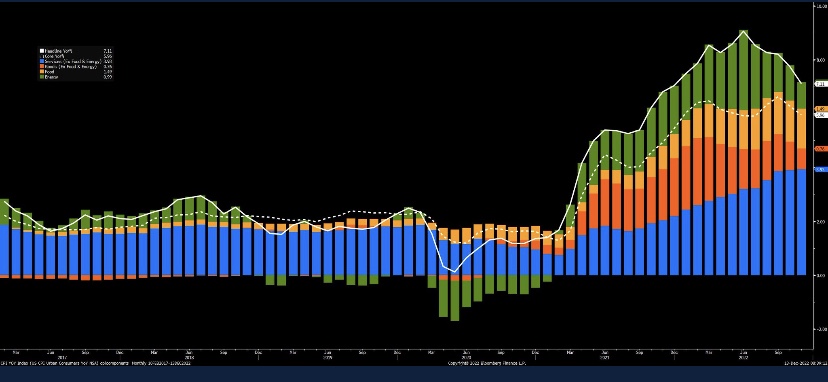

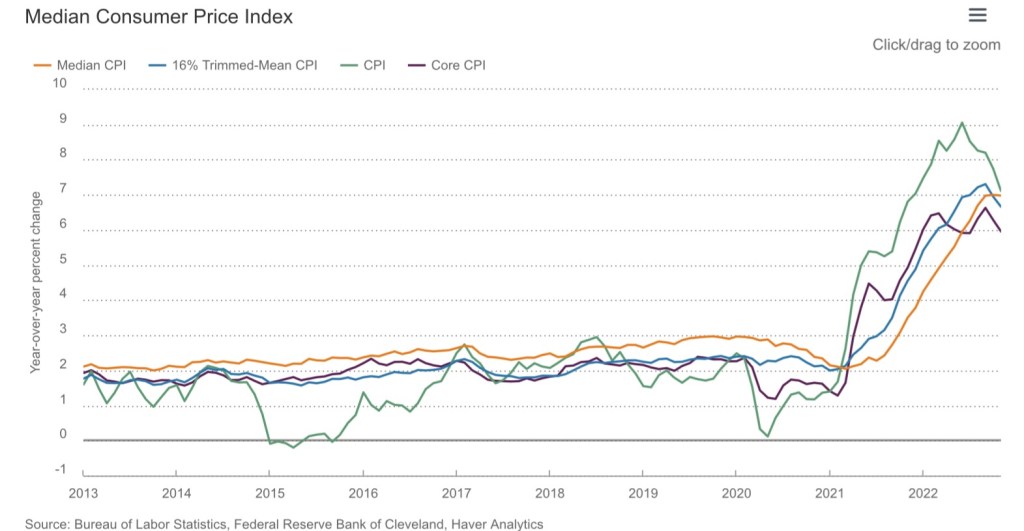

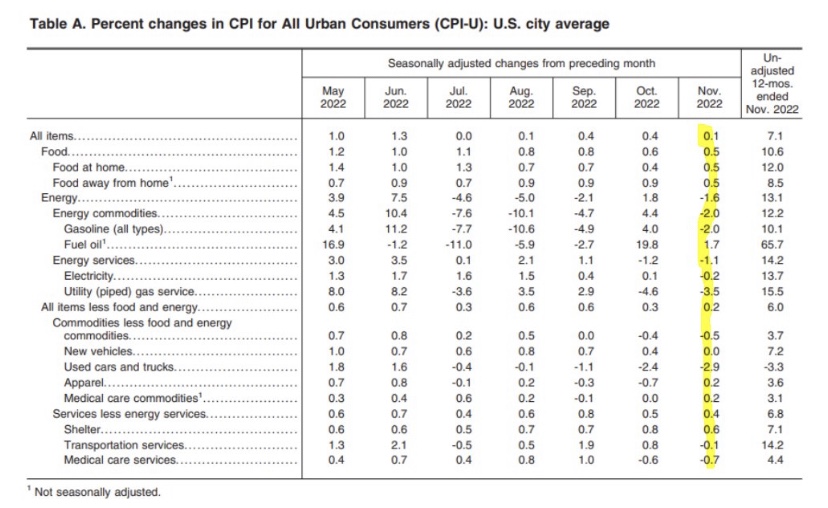

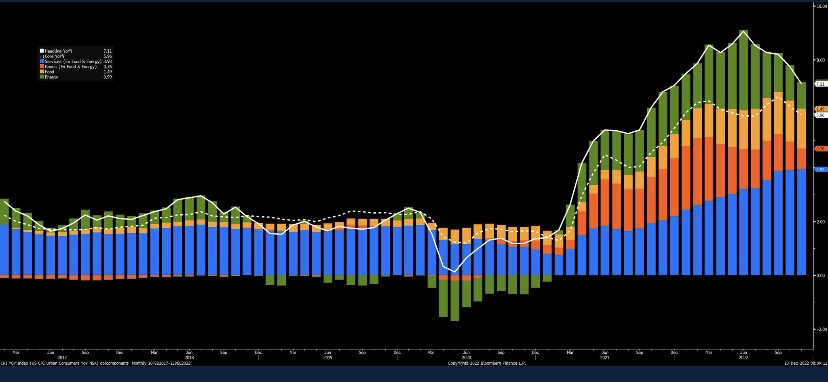

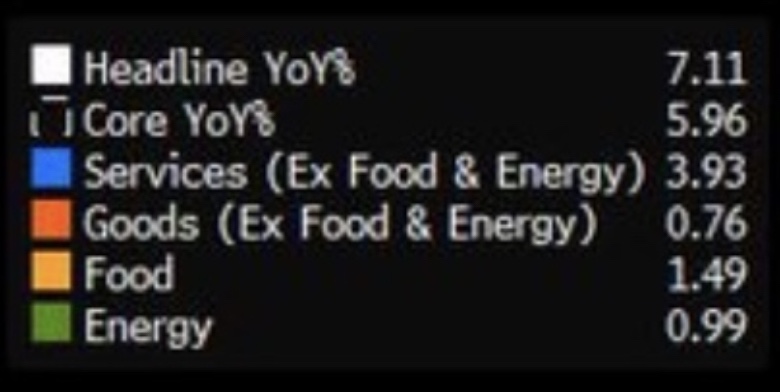

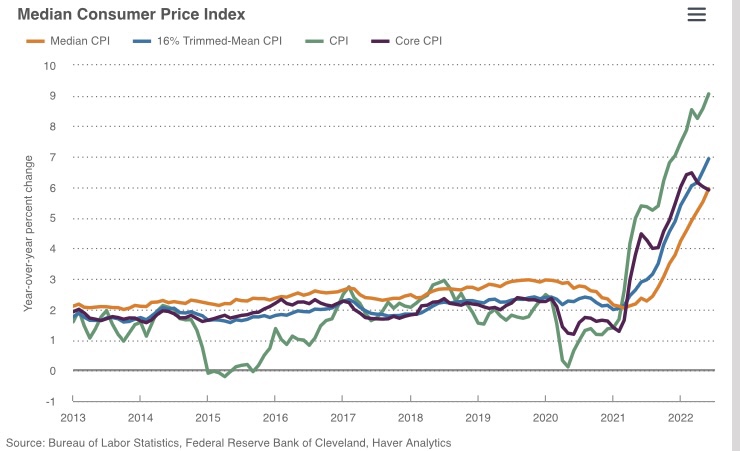

The inflation news was great last week, with both the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Producer Price Index (PPI) reported below expectations. Month-over-month, the increase in the overall CPI was just 0.2%. Year-over-year, CPI inflation was 3%, down from 9% a year ago. Of course, contrary to Joe Biden’s ridiculous claims, this inflation news came despite, and not because of, the pernicious effects of “Bidenomics”. But that aside, just like that, we heard proclamations that the Federal Reserve had finally succeeded in bringing real short-term interest rates into positive territory. Finally, some said, Fed policy had moved into more restrictive territory. But in fact, real rates moved above zero months ago.

The popular rate narrative is based on the fact that the effective Fed Funds rate is now 5.08% while “headline” CPI inflation fell to 2.97%. That would give us a real Fed Funds rate of 3.11%… if that sort of calculation made sense. Here’s an appropriate reaction from Kevin Erdman:

“The short term rate minus trailing 12 month inflation is not a thing. It’s an irrelevant number. Nothing about June 2022 inflation has anything to do with the real fed funds rate in July 2023.”

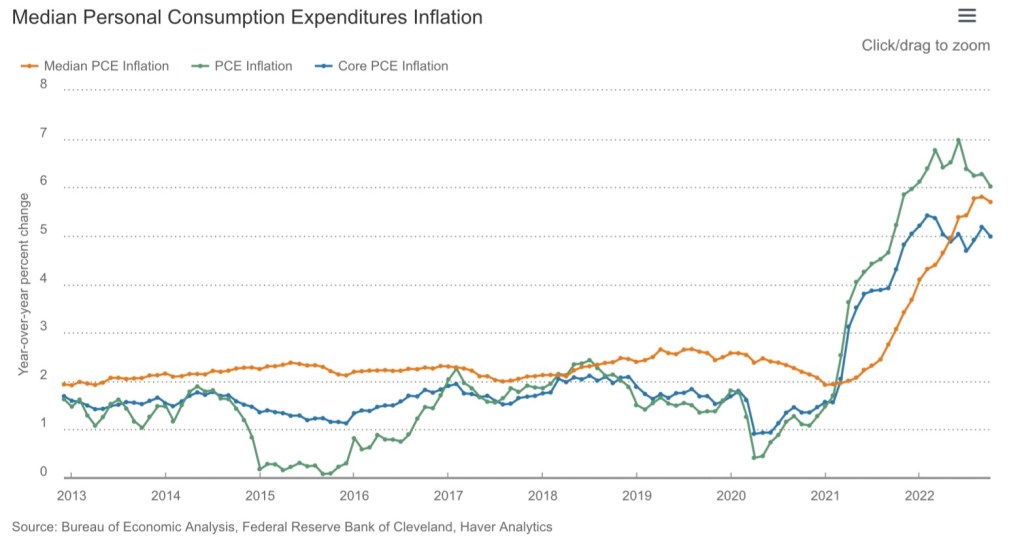

His statement generalizes to interest rates at any maturity less a corresponding measure of trailing inflation. They are all irrelevant. A proper real rate of interest must incorporate a measure of inflation expectations. Survey data is often used for this purpose, but a better measure can be taken from market expectations by comparing a nominal Treasury rate with a rate on an inflation-indexed Treasury (TIPS) of the same maturity. This is a fairly convenient approach.

Below, we can see that the real one-year Treasury rate has been positive since last November.

And here is the real one-month Treasury rate:

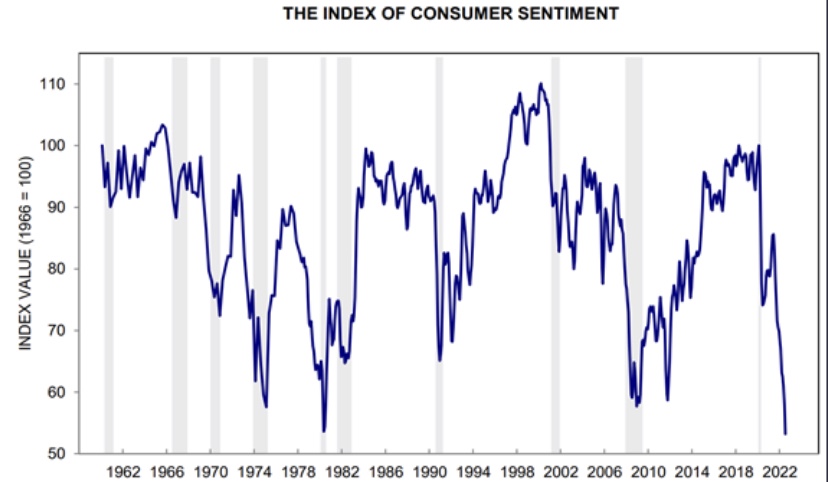

Again, these charts suggest that real short-term rates have been positive much longer than some believe. Whether that represents a “restrictive policy stance” by the Federal Reserve is another matter. We know the Fed has tightened policy, but that began after the notably loose policy conducted throughout the pandemic. Have we truly crossed the threshold into “tightness”?

Here’s the effective (nominal) federal funds rate over the past year.

This rate is under fairly direct control by the Fed, and it is the primary focus of most Fed watchers. It’s an overnight lending rate on loans of reserves between banks, so to adjust it precisely for expected inflation requires an annualized, overnight inflation rate. That’s pretty tricky!

Finding a published measure of expected inflation over durations of less than a year forward is difficult. One can derive one or use a longer-term rate of expected inflation as a proxy, with the proviso that near-term expectations might be more extreme than the proxy, especially if inflation is expected to change from its current pace. Here are one-year inflation expectations over the past year from a Cleveland Fed model that utilizes TIPS returns and other data.

So inflation expectations have declined substantially. If we compare them with short-term interest rates or the effective fed funds rate over the past year, it’s likely the real fed funds rate climbed above zero before the end of the first quarter of 2023. It might even have exceeded the so called “neutral” real Fed funds rate (R*), which was estimated by the Fed to be 1.14% in the first quarter of 2023. A real Fed funds rate above that level would have been deemed restrictive in the first quarter.

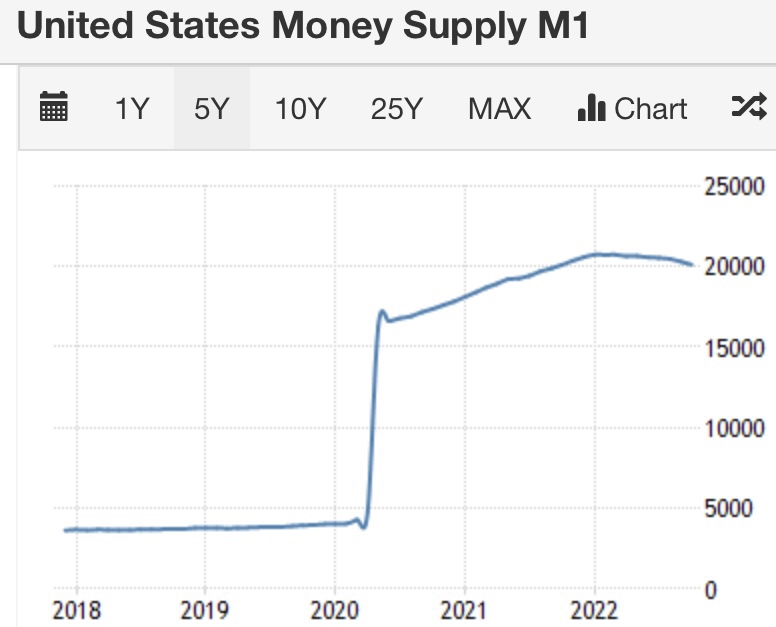

My own view is that changes in the Fed funds rate are not at the heart of the transmission mechanism from monetary policy to the real economy. The monetary aggregates are more reliable guides. The broad money stock M2 has been edging lower for well over a year now. That certainly qualifies as a restrictive move, but there is still a lot of excess liquidity out there, left over from the pandemic deluge engineered by the Fed.

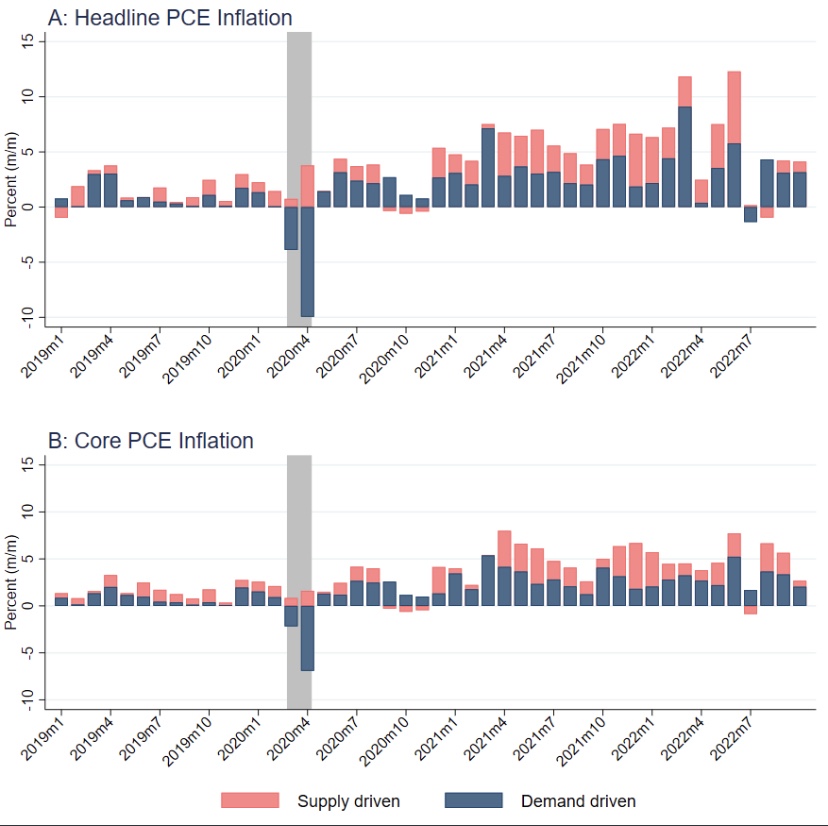

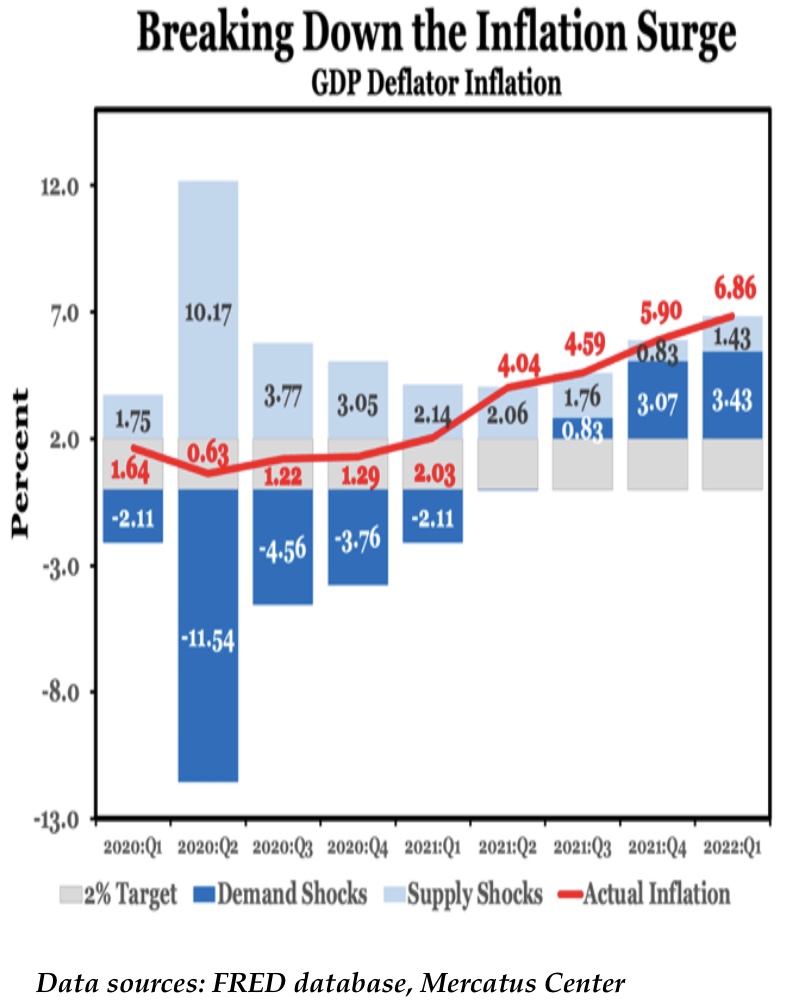

The good reports last week might not mark the end of the inflation problem. There are still price pressures from both the demand and supply-sides. Furthermore, to put things in context, the month-to-month increases in May and June of last year were large, which helped to hold down the 12-month increases this May and June. But the CPI was flat during the second half of last year. That means month-to-month inflation over the next six months may well translate into an escalation of year-over-year inflation. That might or might not be turn out to be meaningful, but it would provide a pretext for additional Fed tightening.

The main point of this post is that real interest rates cannot be calculated on the basis of reported inflation over prior months. Doing so at this juncture understates the degree of monetary tightening in terms of short-term rates. Real interest rates can only be determined by nominal rates relative to expectations of future inflation. This gives a more accurate picture of actual credit market conditions and the Fed’s rate policy stance.