Tags

Core PCE Inflation, Federal Deficit, Federal Reserve, Flexible Average Inflation Targeting, Hard Landing, Helicopter Drop, Higher for Longer, Nominal GDP Targeting, Pandemic Relief Payments, Quantitative Tightening, Scott Sumner, Soft Landing, Tight Money, Wage Inflation

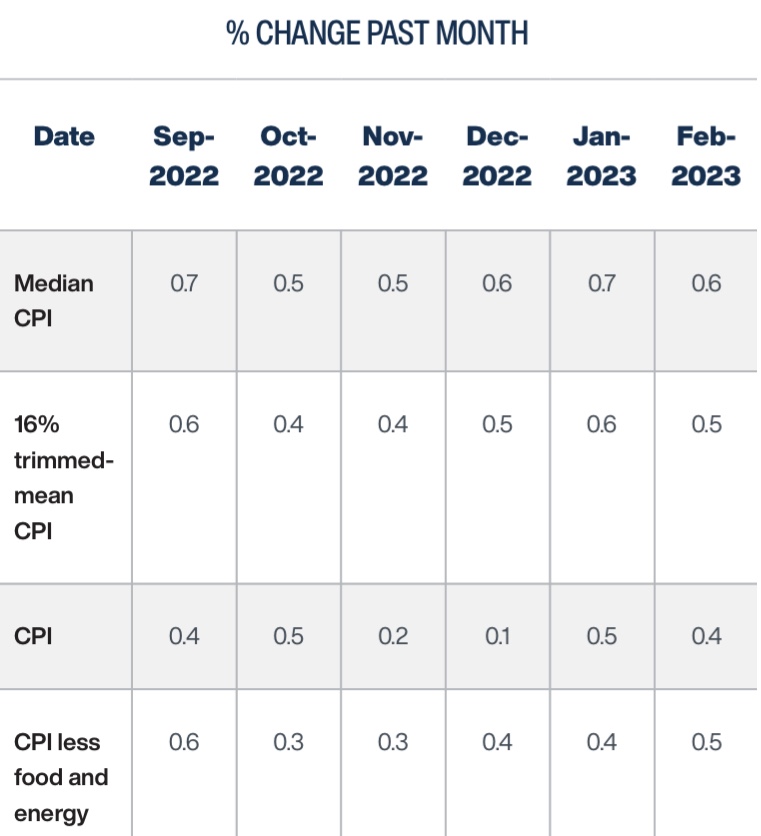

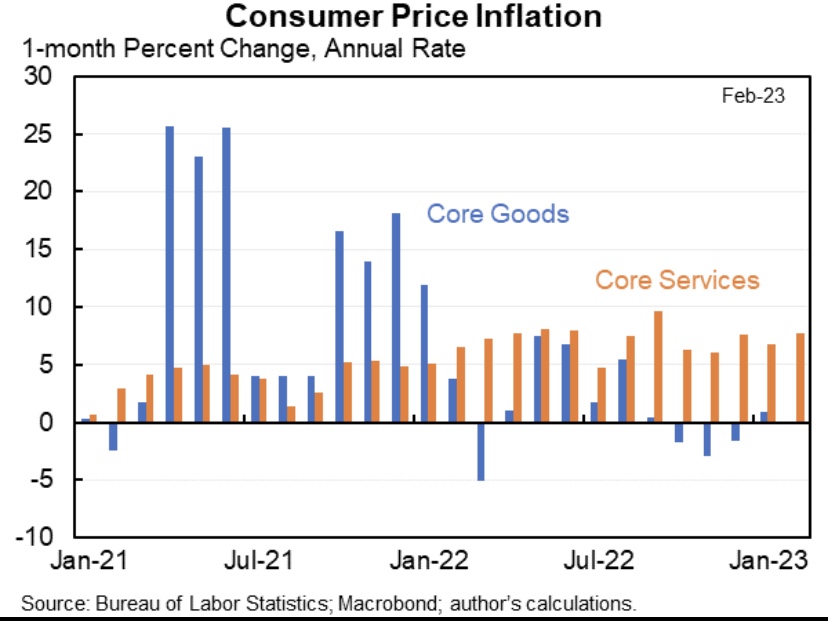

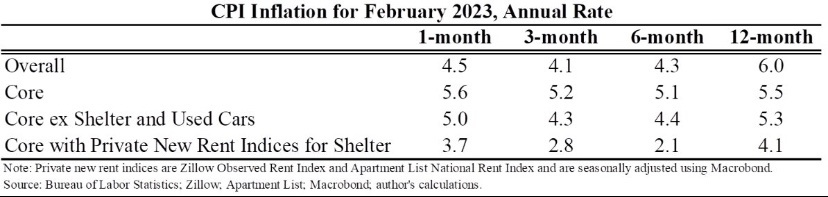

The Fed’s “higher for longer” path for short-term interest rates lingers on, and so does inflation in excess of the Fed’s 2% target. No one should be surprised that rate cuts aren’t yet on the table, but the markets freaked out a little with the release of the February CPI numbers last week, which were higher than expected. For now, it only means the Fed will remain patient with the degree of monetary restraint already achieved.

Dashed Hopes

As I’ve said before, there was little reason for the market to have expected the Fed to cut rates aggressively this year. Just a couple of months ago, the market expected as many as six quarter-point cuts in the Fed’s target for the federal funds rate. The only rationale for that reaction would have been faster disinflation or the possibility of an economic “hard landing”. A downturn is not out of the question, especially if the Fed feels compelled to raise its rate target again in an effort to stem a resurgence in inflation. Maybe some traders felt the Fed would act politically, cutting rates aggressively as the presidential election approaches. Not yet anyway, and it seems highly unlikely.

There is no assurance that the Fed can succeed in engineering a “soft landing”, i.e., disinflation to its 2% goal without a recession. No one can claim any certainty on that point — it’s too early to call, though the odds have improved somewhat. As Scott Sumner succinctly puts it, a soft landing basically depends on whether the Fed can disinflate gradually enough.

It’s a Demand-Side Inflation

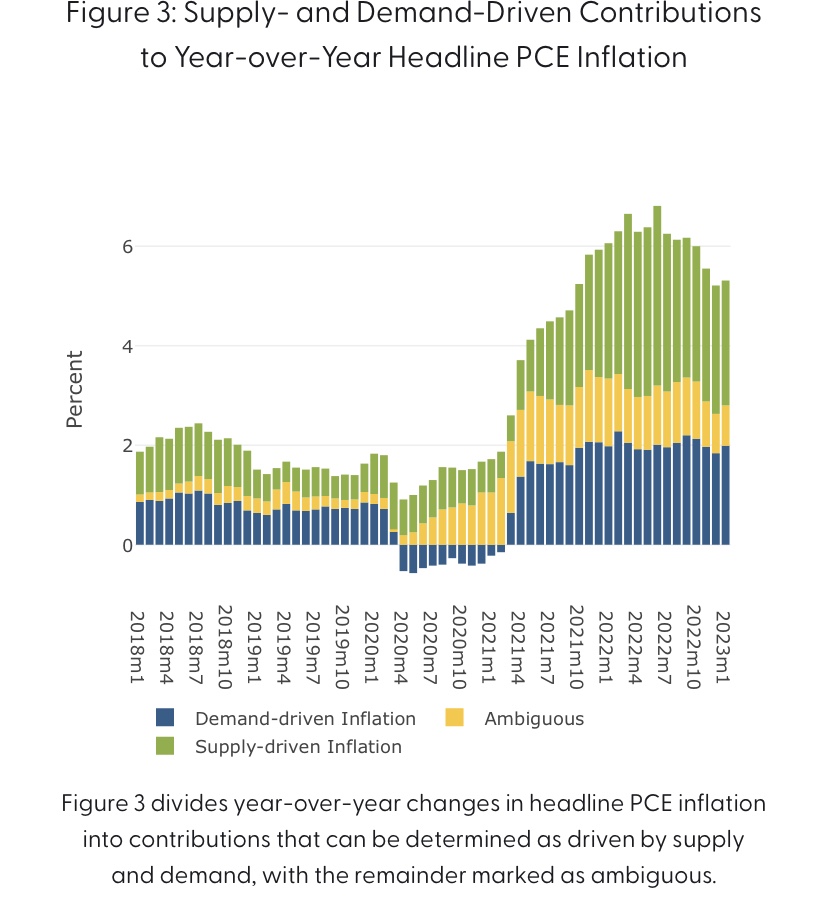

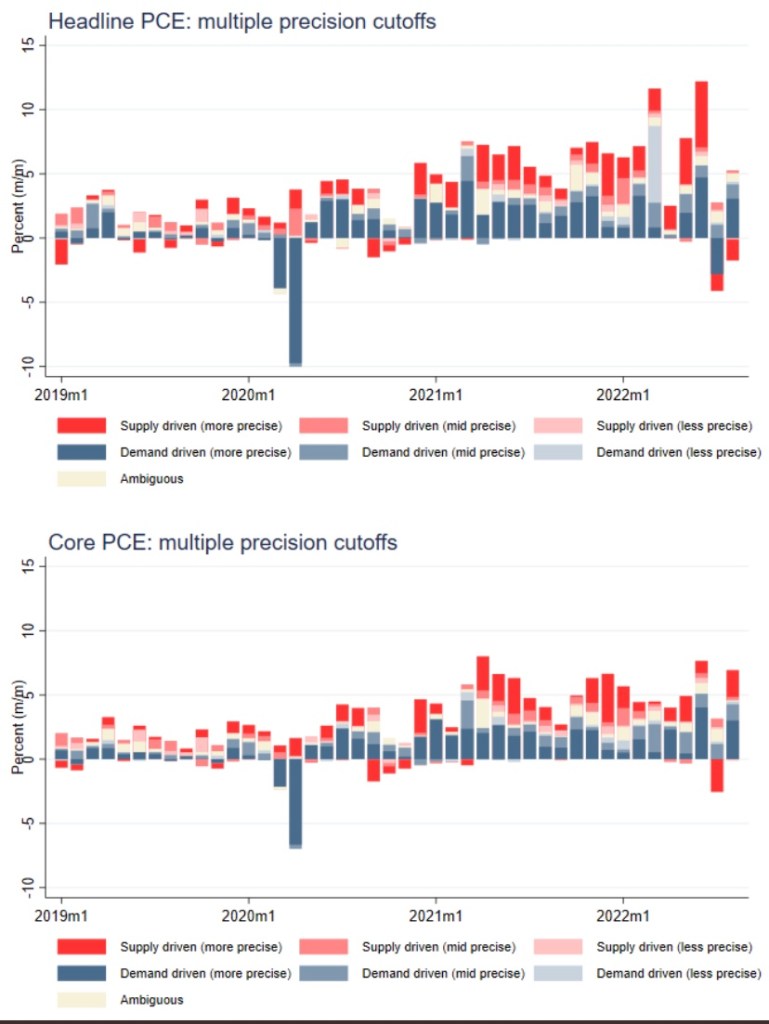

I’d like to focus a little more on Sumner’s perspective on Fed policy because it has important implications for the outlook. Sumner is a so-called market monetarist and a leading proponent of nominal GDP level targeting by the Fed. He takes issue with those ascribing the worst of the pandemic inflation to supply shocks. There’s no question that disruptions occurred on the supply side, but the Fed did more than accommodate those shocks in attempting to minimize their impact on real output and jobs. In fact, it can fairly be said that a Fed / Treasury collaboration managed to execute the biggest “helicopter drop” of money in the history of the world, by far!

That “helicopter drop” consisted of pandemic relief payments, a fiscal maneuver amounting to a gigantic monetary expansion and stimulus to demand. The profligacy has continued on the fiscal side since then, with annual deficits well in excess of $1 trillion and no end in sight. This reflects government demand against which the Fed can’t easily act to countervail, making the job of achieving a soft landing that much more difficult.

The Treasury, however, is finding a more limited appetite among investors for the flood of bonds it must regularly sell to fund the deficit. Recent increases in long-term Treasury rates reflect these large funding needs as well as the “higher-for-longer” outlook for short-term rates, inflation expectations, and of course better perceived investment alternatives.

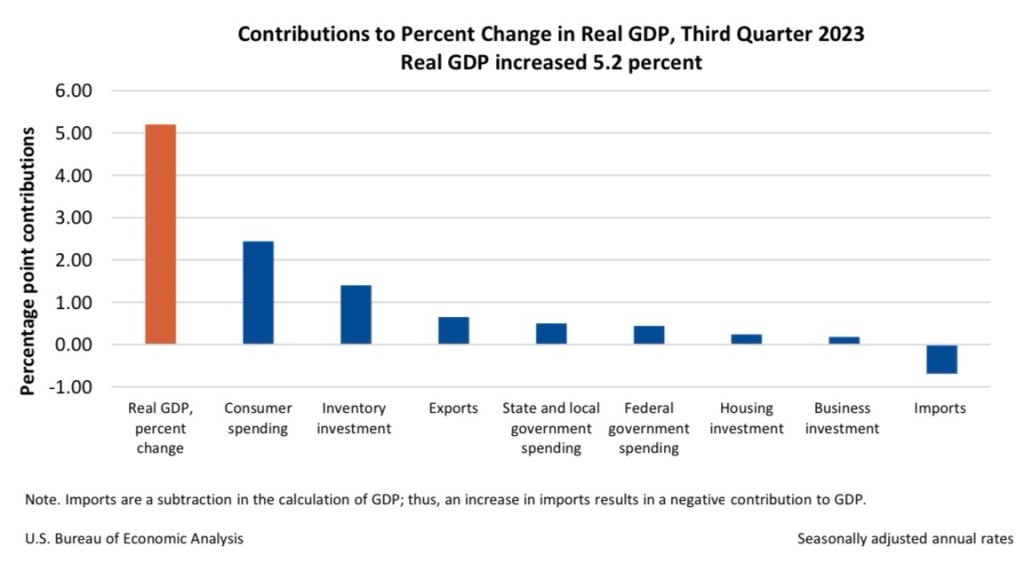

The Nominal GDP Proof

There should be no controversy that inflation is a demand-side problem. As Summer says, supply shocks tend to reverse themselves over time, and that was largely the case as the pandemic wore on in 2021. Furthermore, advances in both real and nominal GDP have continued since then. The difference between the two is inflation, which again, has remained above the Fed’s target.

So let’s see… output and prices both growing? That combination of gains demonstrates that demand has been the primary driver of inflation for three-plus years. Restrictive monetary policy is the right prescription for taming excessive demand growth and inflation.

Here’s Sumner from early March (emphasis his), where he references flexible average inflation targeting (FAIT), a policy the Fed claims to be following, and nominal GDP level targeting (NGDPLT):

“Over the past 4 years, the PCE price index is up 16.7%. Under FAIT it should have risen by 8.2% (i.e., 2%/year). Thus we’ve had roughly 8.5% excess inflation (a bit less due to compounding.)

Aggregate demand (NGDP) is up by 27.6%. Under FAIT targeting (which is similar to NGDPLT) it should have been up by about 17% (i.e., 4%/year). So we’ve had a bit less than 10.6% extra demand growth. That explains all of the extra inflation.”

Is Money “Tight”?

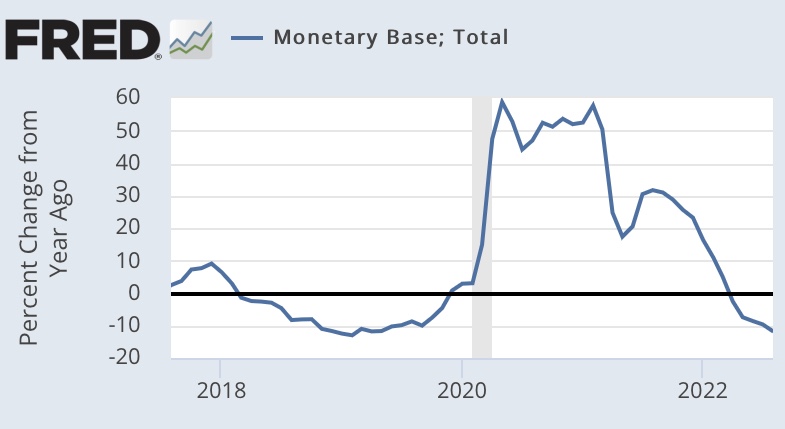

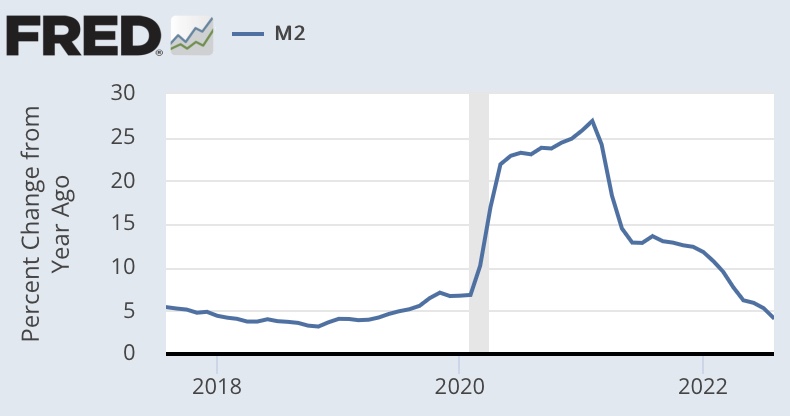

The Fed got around to tightening policy in the spring of 2022, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that policy ever advanced to the “tight” stage. Sumner has been vocal in asserting that the Fed’s policy hasn’t looked especially restrictive. Money growth feeds demand and ultimately translates into nominal GDP growth (aggregate demand). The latter is growing too rapidly to bring inflation into line with the 2% target. But wait! Money growth has been moderately negative since the Fed began tightening. How does that square with Sumner’s view?

In fact, the M2 money supply is still approximately 35% greater than at the start of the pandemic. There’s still a lot of M2 sloshing around out there, and the Fed’s portfolio of securities acquired during the pandemic via “quantitative easing” remains quite large ($7.5 trillion). Does this sound like tight money?

Again, Sumner would say that with nominal GDP ripping ahead at 5.7%, the Fed can’t be credibly targeting 2% inflation given an allowance for real GDP growth at trend of around 1.8% (or even somewhat greater than that). It’s an even bigger stretch if M2 velocity (V — turnover) continues to rebound with higher interest rates.

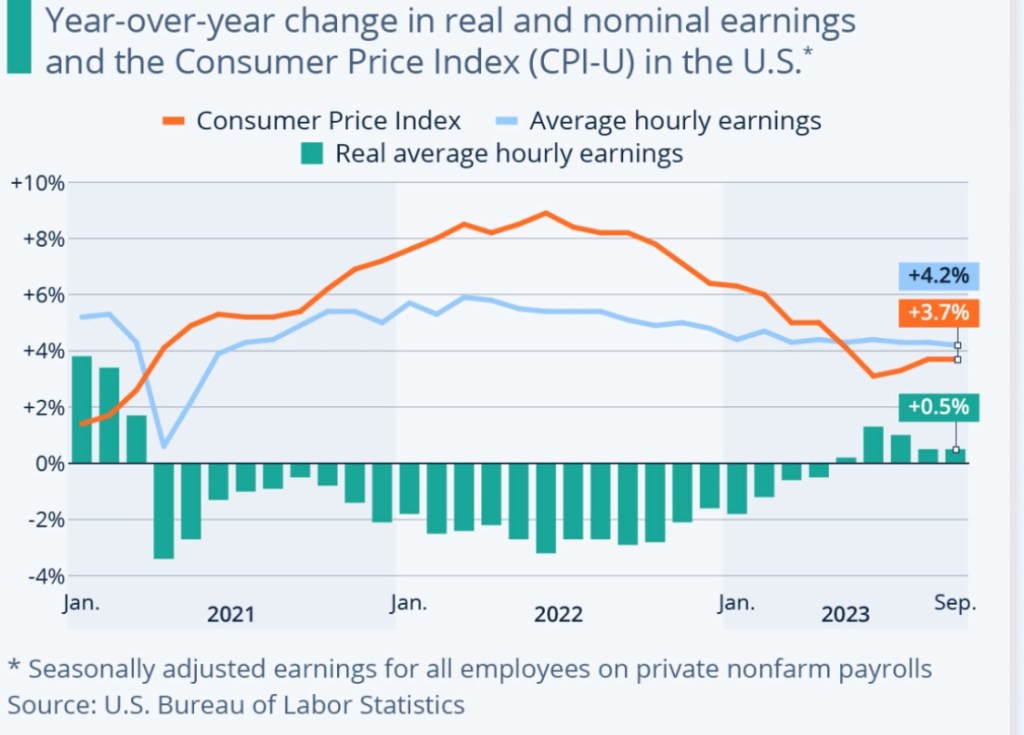

Wage growth also exceeds a level consistent with the Fed’s target. The chart below shows the gap between price inflation and wage inflation that left real wages well below pre-pandemic levels. Since early 2023, wages have made up part of that decline, but stubborn wage inflation can impede progress against price inflation.

Just Tight Enough?

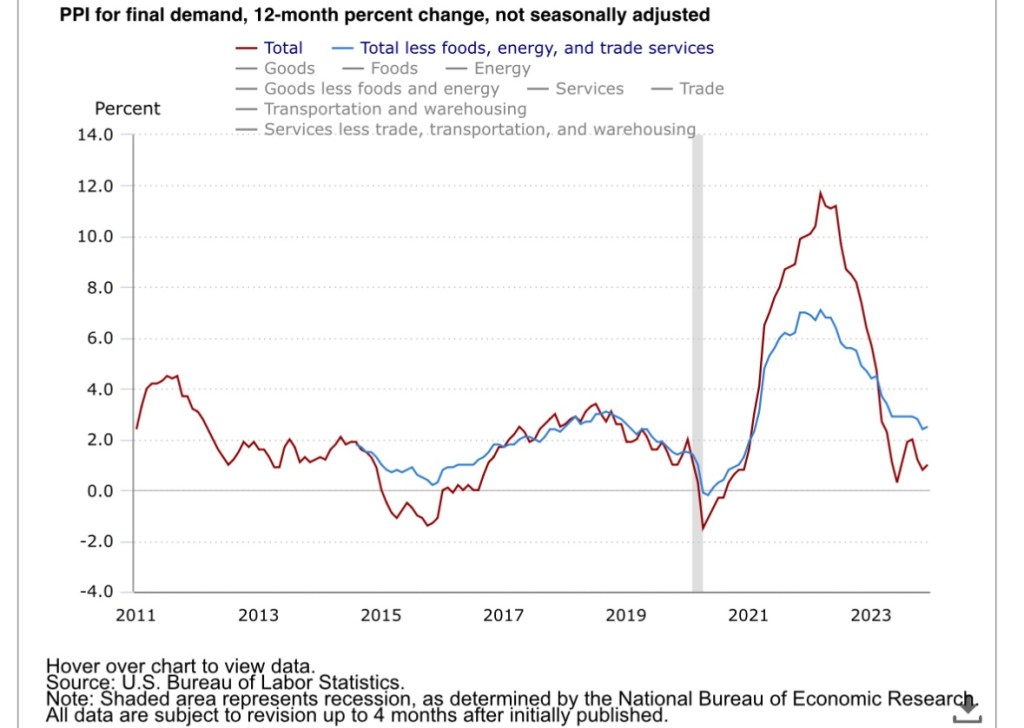

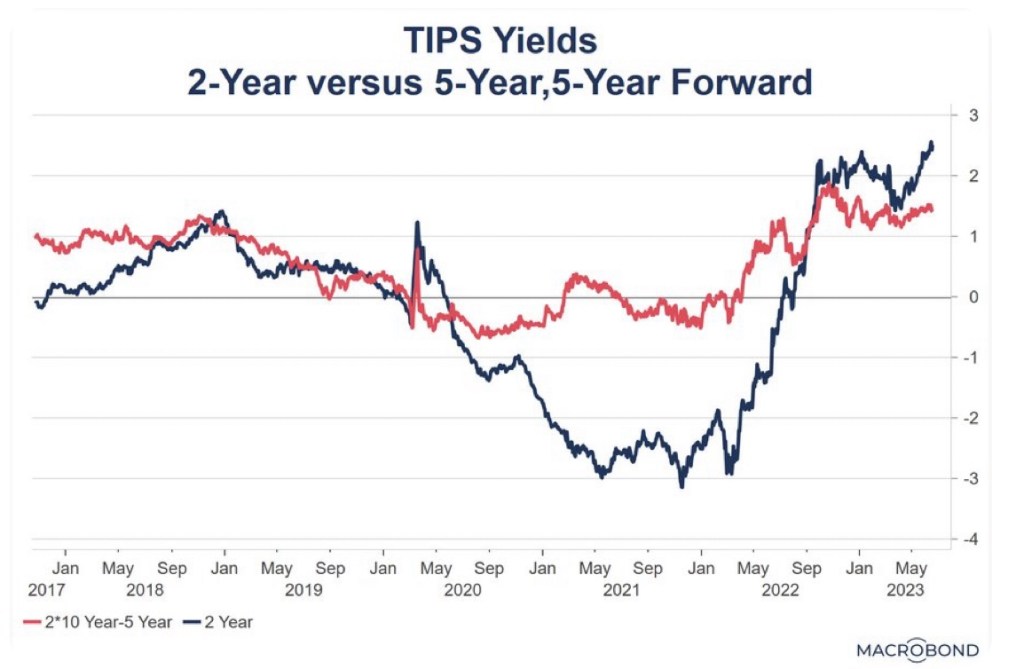

Despite Sumner’s doubts, there are arguments to be made that Fed policy qualifies as restrictive. Even moderate declines in liquidity can come as a shock to markets grown accustomed to torrents from the money supply firehose. And to the extent that inflation expectations have declined, real interest rates may be higher now than they were in early November. In any case, it’s clear the market was disappointed in the higher-than-expected CPI, and traders were not greatly assuaged by the moderate report on the PPI that followed.

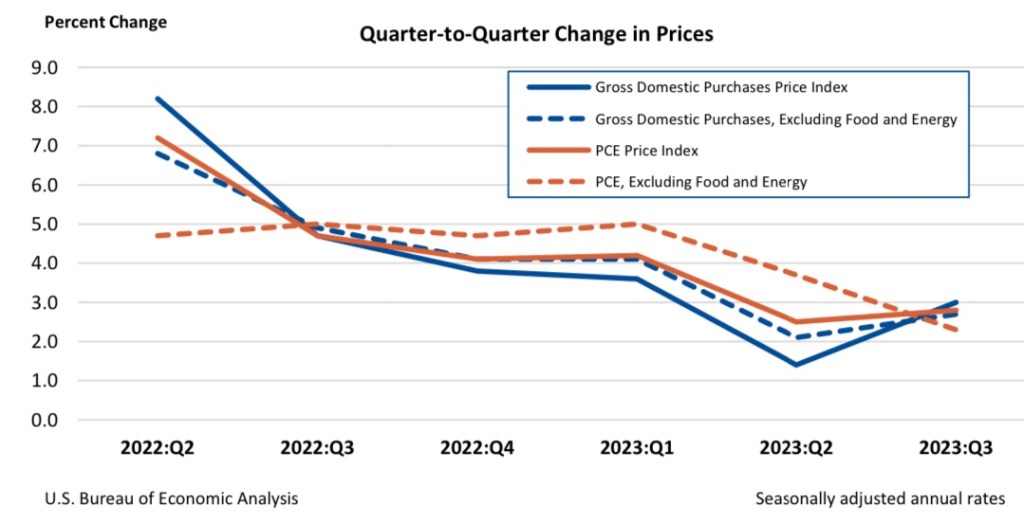

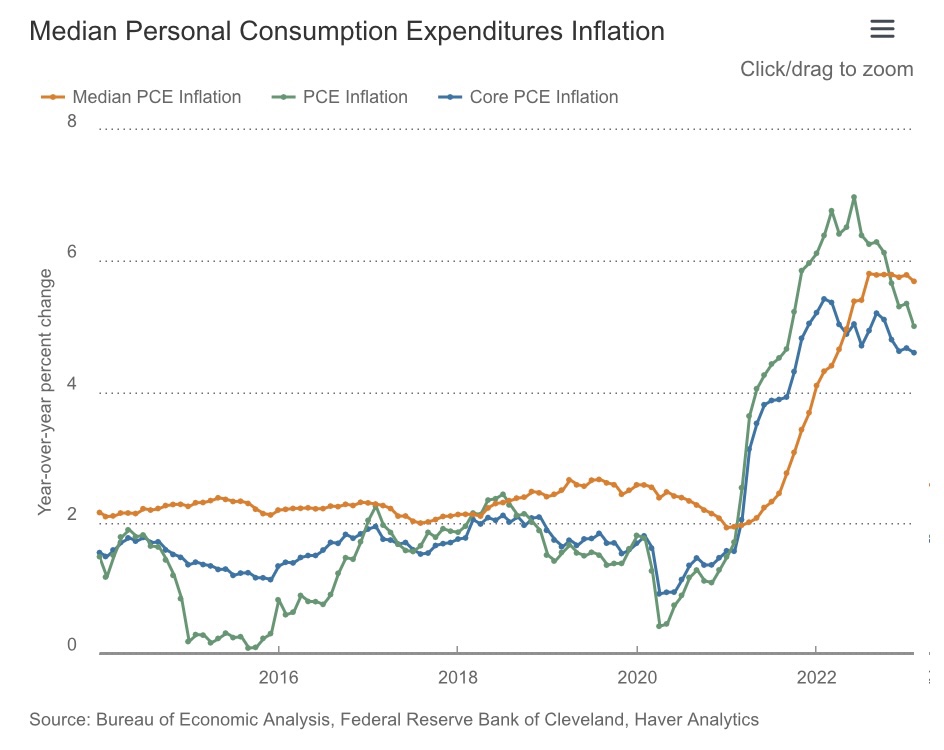

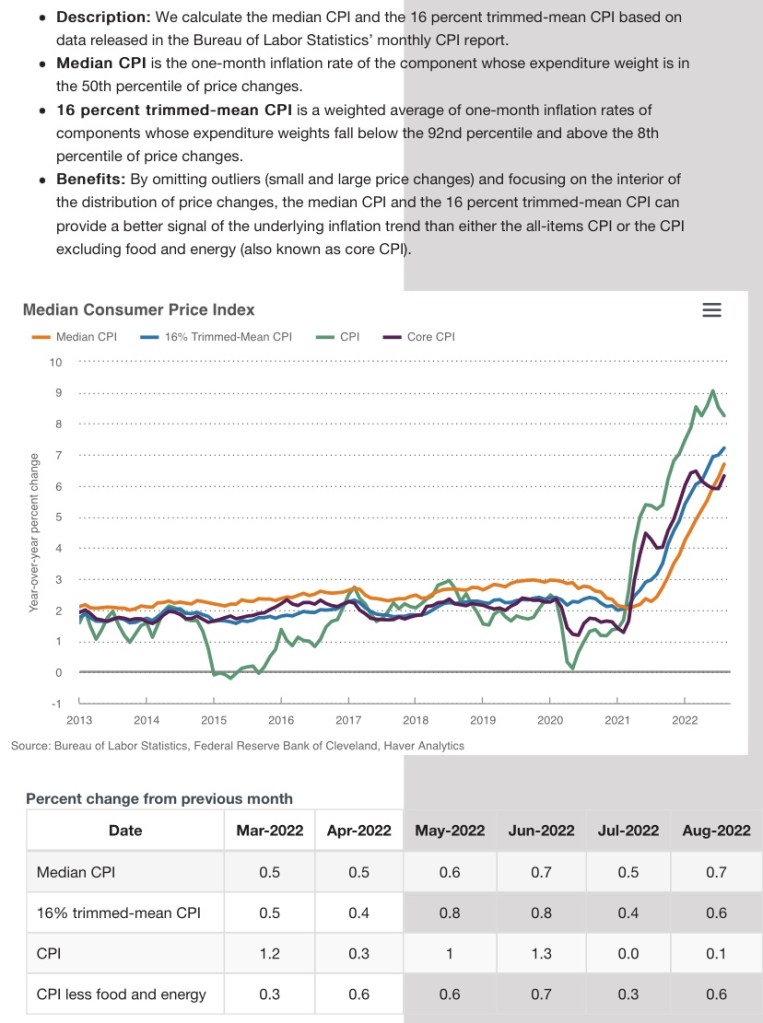

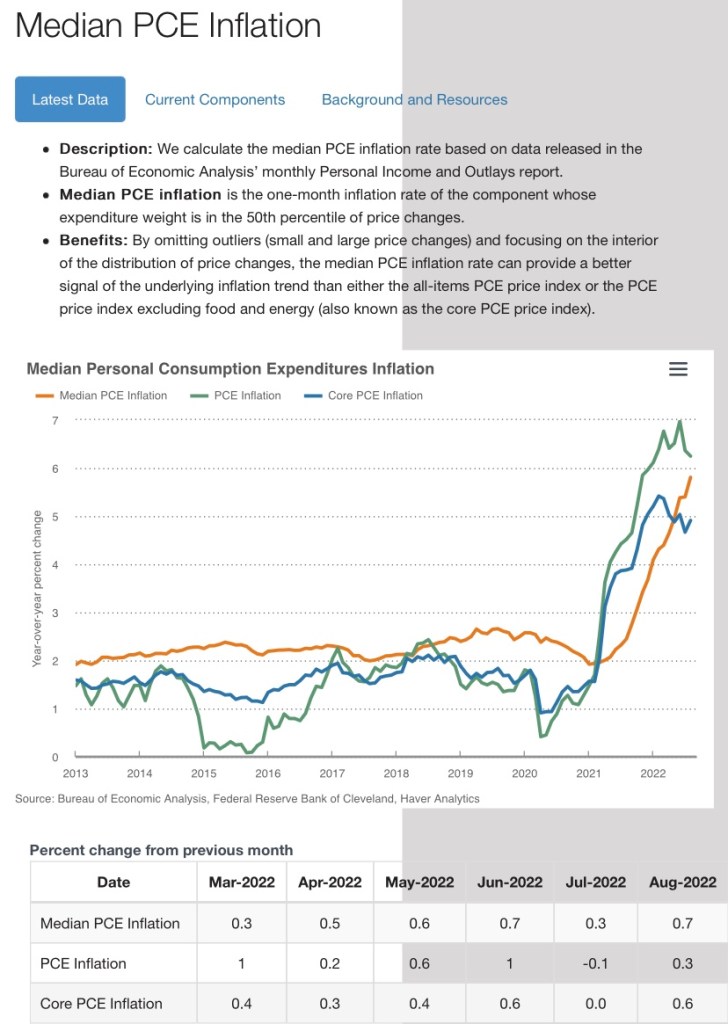

However, the Fed pays closest attention to another price index: the core deflator for personal consumption expenditures (PCE). Inflation by this measure is trending much closer to the Fed’s target (see the second chart below). Still, from the viewpoint of traders, many of whom, not long ago, expected six rate cuts this year, the reality of “higher for longer” is a huge disappointment.

Danger Lurks

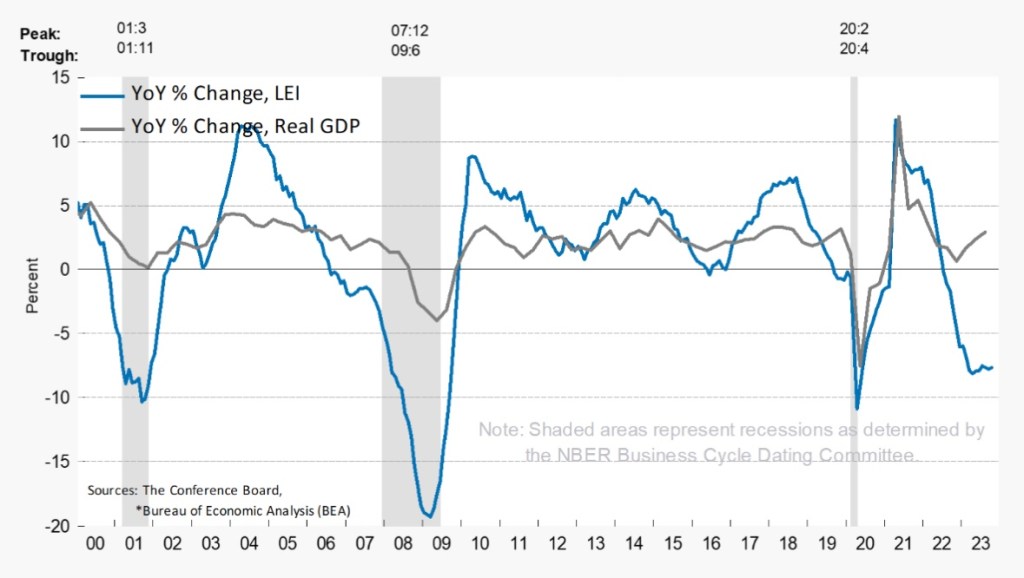

As I noted, many believe the odds of a soft landing have improved. However, the now-apparent “stickiness” of inflation and the knowledge that the Fed will standby or possibly hike rates again has rekindled fears that the economy could turn south before the Fed elects to cut its short-term interest rate target. That might surprise Sumner in the absence of more tightening, as his arguments are partly rooted in the continuing strength of aggregate demand and nominal GDP growth.

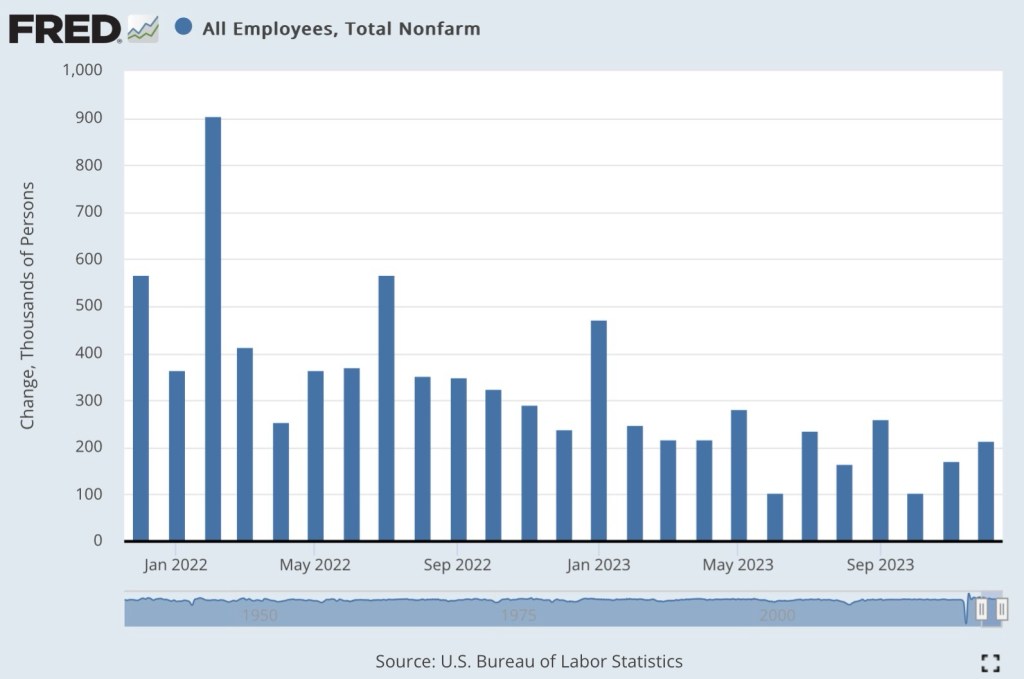

There’s a fair degree of consensus that the labor market remains strong, which underscores Sumner’s doubts as to the actual tenor of monetary policy. The March employment numbers were deceptive, however. The gain in civilian employment was just shy of 500,000, but that gain was entirely in part-time employment. Full-time employment actually declined slightly. In fact, the same is true over the prior 12 months. And over that period, the number of multiple jobholders increased by more than total employment. Increasing reliance on part-time work and multiple jobs is a sign of stress on household budgets and that firms may be reluctant to commit to full-time hires. From the establishment survey, the gain in nonfarm employment was dominated once again by government and health care. These numbers hardly support the notion that the economy is on solid footing.

There are other signs of stress: credit card delinquencies hit an all-time high in February. High interest rates are taking a toll on households and business borrowers. Retail sales were stronger than expected in March, but excess savings accumulated during the pandemic were nearly depleted as of February, so it’s not clear how long the spending can last. And while the index of leading indicators inched up in February, it was the first gain in two years and the index has shown year/over-year declines over that entire two-year period.

Conclusion

It feels a little hollow for me to list a series of economic red flags, having done so a few times over the past year or so. The risks of a hard landing are there, to be sure. The behavior of the core PCE deflator over the next few months will have much more influence on the Fed policy, as would any dramatic changes in the real economy. The “data dependence” of policy is almost a cliche at this point. The Fed will stand pat for now, and I doubt the Fed will raise its rate target without a dramatic upside surprise on the core deflator. Likewise, any downward rate moves won’t be forthcoming without more softening in the core deflator toward 2% or definitive signs of a recession. So rate cuts aren’t likely for some months to come.