Tags

Capital Gains, David Splinter, Emmanuel Saez, Fiscal Income, Founders, Gerald Auten, Hoover Institution, Income Redistribution, Inequality, Inheritance, Joel Kotkin, John Cochrane, Joint Committee on Taxation, Omitted Income, Paul Graham, Progressive Taxes, Thomas Piketty, Transfer Oayments

What’s to like about inequality?

That depends on how it happened and on the conditions governing its future evolution. Inequality is a fact of life, and no social or economic system known to man can avoid or eliminate it. It’s “bad” in the sense that “not everybody gets a prize,” but inequality in a free market economic system arises out of the same positive dynamic that fosters achievement in any kind of competition. Even the logic underlying the view that inequality is “bad” is not consistent: we can be more equal if the rich all lose $1,000,000 and the poor all lose $1,000, but that won’t make anyone happy.

Unequal Rewards Are Natural

Many activities contribute to general prosperity and create unequal rewards as a by-product. A capitalist system rewards knowledge, effort, creativity, and risk-taking. Those who are very good at creating value earn commensurate rewards, and in turn, they often create rewarding opportunities for others who might participate in their enterprises. A system of just incentives and rewards also requires that property rights be secure, and that implies that wealth can be accumulated more readily by those earning the greatest rewards.

Equality can be decreed only by severely restricting the rewards to productive effort, and that requires a massive imbalance of power. The state, and those who direct its actions, always have a monopoly on legal coercion. In practice, the power to commandeer value created by others means that economic benefits will waft under the noses of apparatchiks. The raw power and economic benefits usurped under such an authoritarian regime cannot be competed away, and efficiency and value are seldom prioritized by state monopolists. The egalitarian pretense thus masks its own form of extreme inequality and decline. Inequality is unavoidable in a very real sense.

Measuring Trends in Inequality

Beyond those basic truths, the facts do not support the conventional wisdom that inequality has grown more extreme. A research paper by Gerald Auten and David Splinter corrects many of the shortcomings of commonly-cited sources on income inequality. Auten works for the U.S. Treasury, and Splinter is employed by the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation. They find that higher transfer payments and growing tax progressivity since the early 1960s kept the top after-tax income share stable.

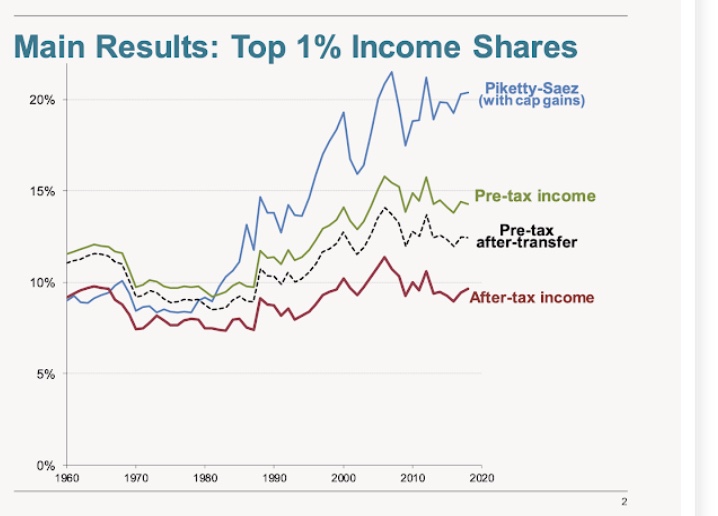

John Cochrane shares the details of a recent presentation made by Auten and Splinter (AS) at the Hoover Institution. A few interesting charts follow:

The blue “Piketty-Saez” (PS) line at the top uses an income measure from well-known research by Thomas Piketty and Emanuel Saez that contributed to the narrative of growing income inequality. The PS line is based on tax return information (fiscal income), but it embeds several distortions.

Realized capital gains are counted there, which misrepresents income shares because the realization of gains does not mark the point at which the true gains occur. Typically, the wealth exists before and after the gains are realized. Realized gains are often a function of changes in tax law and investor reaction to those changes. Moreover, neither realized nor unrealized gains represent income earned in production; instead, they capture changes in asset prices.

Income earned in production is about a third more than the income measure used by PS, even with the capital gains distortion. This omitted income and its allocation across earners is the subject of detailed analysis by AS. Their analysis is consistent in its focus on individual taxpayers, rather than households, which eliminates another upward bias in the PS line created by a secular decline in marriage rates. Then, AS consider the reallocation of income shares due to taxes and transfer payments. After all that, the income share of the top 1% shifts all the way down to the red line in the chart. The most recent observations put the share about where it was in the 1960s.

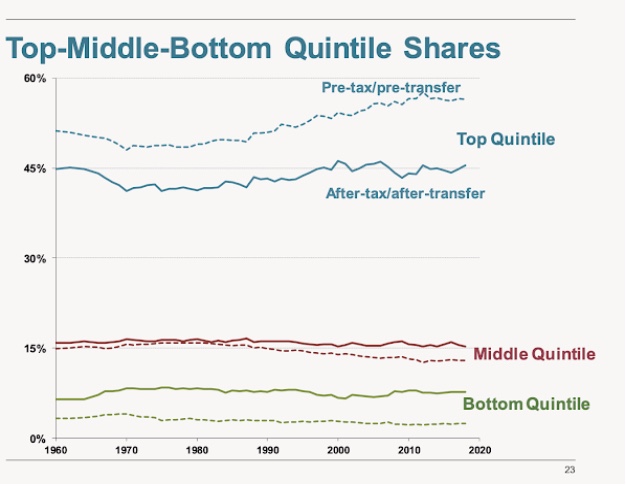

The next chart shows income shares for broader segments: the top, middle, and lowest 20% of the income distribution. Taxes and transfers cause massive changes in the calculated shares and their trends over time. Again, these shares remain about where they were in the 1960s, contradicting the popular narrative that high earners are gobbling up ever larger pieces of the pie.

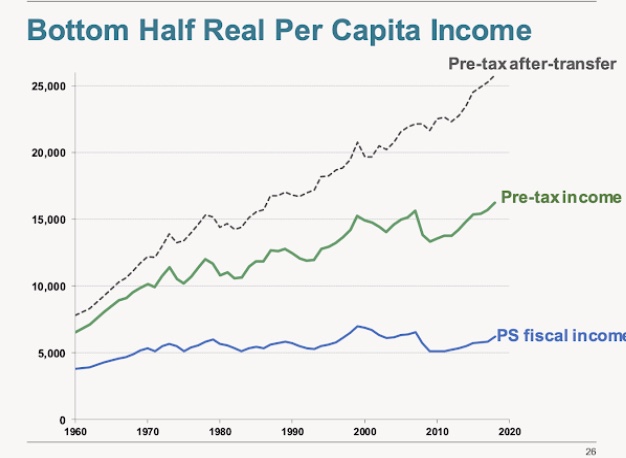

If income shares have remained about the same since the 1960s, that means high and low earners have made roughly equivalent income gains over that time. The next chart demonstrates that the bottom half of the income distribution has indeed seen significant growth in real incomes, despite the false impression created by PS and the common misperception of stagnant income growth among the working class.

More Distributional Tidbits

In a sense, all this is misleading because there is so much migration across the income distribution over time. Traditional calculations of income shares are “cross-sectional”, meaning they compare the same slices of the distribution at different points in time. But people near the low end in 1990 are not the same people near the bottom today. The same is true of those near the top and those in the middle. Income grows over time, and those lower in the distribution typically migrate upward as they age and acquire skills and work experience. Upward migration in income share is the general tendency, but there is some downward migration as well. Abandoning the cross-sectional view causes the typical story-line of rising income inequality to unravel.

There are many other interesting facts (and some great charts) in the AS paper and in Cochran’s post. One in particular shows that the average federal tax rate paid by the top 1% trended upward from the 1960s through the mid-1990s before flattening and trending slightly downward. This contradicts the assertion that high earners paid much higher taxes before the 1960s than today. In fact, the tax base broadened over that time, more than compensating for declines in marginal tax rates.

Given the fact that more exacting measures of inequality haven’t changed much over the years, does that imply that redistributional policies have worked to keep the income distribution from worsening? That seems plausible on its face. If anything, taxes on high earners have increased, as have transfers to low earners and non-earners. Those changes appear to have offset other factors that would have led to greater inequality. However, the framing of the question is inappropriate. Maintaining a given income distribution is not a good thing if it inhibits economic growth. In fact, faster growth in production and greater well-being might well have led to a more unequal distribution of income. In other words, the whole question of offsetting inequality via redistribution is something of a chimera in the absence of a reliable counter-factual.

Wealth

Cochrane has a related post on the sources of wealth in America. Increasingly over the past few decades, wealth has been accumulated by self-made entrepreneurs, rather than through inheritance. That might come as a surprise to many on the left, to the extent that they care. Cochrane quotes Paul Graham on this point:

“In 1982 the most common source of wealth was inheritance. Of the 100 richest people, 60 inherited from an ancestor. There were 10 du Pont heirs alone. By 2020 the number of heirs had been cut in half, accounting for only 27 of the biggest 100 fortunes.

Why would the percentage of heirs decrease? Not because inheritance taxes increased. In fact, they decreased significantly during this period. The reason the percentage of heirs has decreased is not that fewer people are inheriting great fortunes, but that more people are making them.

How are people making these new fortunes? Roughly 3/4 by starting companies and 1/4 by investing. Of the 73 new fortunes in 2020, 56 derive from founders’ or early employees’ equity (52 founders, 2 early employees, and 2 wives of founders), and 17 from managing investment funds.”

The picture that emerges is one of great opportunity and dynamism. While the accumulation of massive fortunes might enrage the Left, these are the kinds of outcomes we should hope for, especially because the success of these new titans of industry is inextricably linked to tremendous value captured by their customers and lucrative opportunities for their employees.

Here’s the best part of Cochrane’s post:

“We should not think about more or less inequality, we should think about the right amount of inequality, or productive vs. rent-seeking sources of inequality. Or, better, whether inequality is a symptom of health or sickness in the economy. Take Paul’s picture of the US economy at face value. What’s a better economy and society? One in which a few oligopolies … , deeply involved with government, run everything — think GM, Ford, IBM, AT&T, defense contractors — and it’s hard to start new innovative fast growing companies? Or the world in which the Bill Gates and Steve Jobs of the world can start new companies, deliver fabulous products and get insanely rich in the process? “

No doubt about it! However, today’s tremendously successful tech entrepreneurs also give us something to worry about. They have become oligarchs capable of suppressing competitive forces through sheer market power, influence, and even control over politicians and regulators. As I said at the top, whether inequality is benign depends upon the conditions governing its evolution. And today, we see the ominous development of a corporate-state tyranny, as decried by Joel Kotkin in this excellent post. Many of the daring tech entrepreneurs who benefitted from advantages endowed by our capitalist system have become autocrats who seek to plan our future with their own ideologies and self-interest in mind.

Conclusion

For too long we’ve heard the Left bemoan an increasingly “unfair” distribution of income. This includes propaganda intended to distort poverty levels in the U.S. The fine points of measuring shifts in the income distribution show that narrative to be false. Moreover, attempting to equalize the distribution of income, or even preventing changes that might occur as a natural consequence of innovation and growth, is not a valid policy objective if our goal is to maximize economic well-being.

The worst thing about inequality is that the poorest individuals are likely to be destitute and with no ability or means of supporting themselves. There is certainly such an underclass in the U.S., and our social safety net helps keep the poorest and least capable individuals above the poverty line after transfer payments. But too often our efforts to provide support interfere with incentives for those who are capable of productive work, which is both demeaning for them and a drain on everyone else. The best prescription for improving the well-being of all is economic growth, regardless of its impact on the distribution of income or wealth.