Tags

Agentic Behavior, AI Bias, AI Capital, AI Risks, Alignment, Artificial Intelligence, Ben Hayum, Bill Gates, Bryan Caplan, ChatGPT, Clearview AI, Dumbing Down, Eliezer Yudkowsky, Encryption, Existential Risk, Extinction, Foom, Fraud, Generative Intelligence, Greta Thunberg, Human capital, Identity Theft, James Pethokoukis, Jim Jones, Kill Switch, Labor Participation Insurance, Learning Language Models, Lesswrong, Longtermism, Luddites, Mercatus Center, Metaculus, Nassim Taleb, Open AI, Over-Employment, Paul Ehrlich, Pause Letter, Precautionary Principle, Privacy, Robert Louis Stevenson, Robin Hanson, Seth Herd, Synthetic Media, TechCrunch, TruthGPT, Tyler Cowen, Universal Basic Income

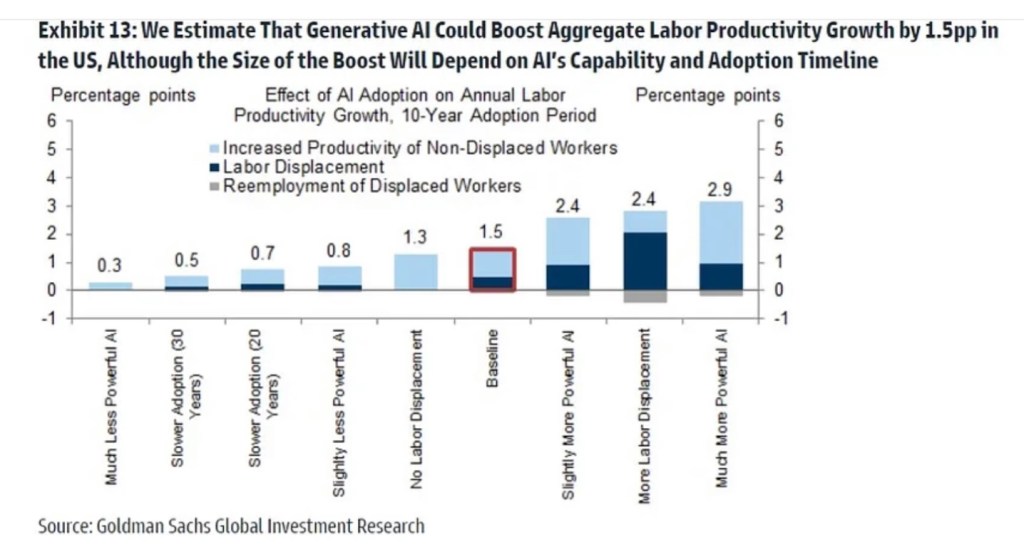

Artificial intelligence (AI) has become a very hot topic with incredible recent advances in AI performance. It’s very promising technology, and the expectations shown in the chart above illustrate what would be a profound economic impact. Like many new technologies, however, many find it threatening and are reacting with great alarm, There’s a movement within the tech industry itself, partly motivated by competitive self-interest, calling for a “pause”, or a six-month moratorium on certain development activities. Politicians in Washington are beginning to clamor for legislation that would subject AI to regulation. However, neither a voluntary pause nor regulatory action are likely to be successful. In fact, either would likely do more harm than good.

Leaps and Bounds

The pace of advance in AI has been breathtaking. From ChatGPT 3.5 to ChatGPT 4, in a matter of just a few months, the tool went from relatively poor performance on tests like professional and graduate entrance exams (e.g., bar exams, LSAT, GRE) to very high scores. Using these tools can be a rather startling experience, as I learned for myself recently when I allowed one to write the first draft of a post. (Despite my initial surprise, my experience with ChatGPT 3.5 was somewhat underwhelming after careful review, but I’ve seen more impressive results with ChatGPT 4). They seem to know so much and produce it almost instantly, though it’s true they sometimes “hallucinate”, reflect bias, or invent sources, so thorough review is a must.

Nevertheless, AIs can write essays and computer code, solve complex problems, create or interpret images, sounds and music, simulate speech, diagnose illnesses, render investment advice, and many other things. They can create subroutines to help themselves solve problems. And they can replicate!

As a gauge of the effectiveness of models like ChatGPT, consider that today AI is helping promote “over-employment”. That is, there are a number of ambitious individuals who, working from home, are holding down several different jobs with the help of AI models. In fact, some of these folks say AIs are doing 80% of their work. They are the best “assistants” one could possibly hire, according to a man who has four different jobs.

Economist Bryan Caplan is an inveterate skeptic of almost all claims that smack of hyperbole, and he’s won a series of bets he’s solicited against others willing to take sides in support of such claims. However, Caplan thinks he’s probably lost his bet on the speed of progress on AI development. Needless to say, it has far exceeded his expectations.

Naturally, the rapid progress has rattled lots of people, including many experts in the AI field. Already, we’re witnessing the emergence of “agency” on the part of AI Learning Language Models (LLMs), or so called “agentic” behavior. Here’s an interesting thread on agentic AI behavior. Certain models are capable of teaching themselves in pursuit of a specified goal, gathering new information and recursively optimizing their performance toward that goal. Continued gains may lead to an AI model having artificial generative intelligence (AGI), a superhuman level of intelligence that would go beyond acting upon an initial set of instructions. Some believe this will occur suddenly, which is often described as the “foom” event.

Team Uh-Oh

Concern about where this will lead runs so deep that a letter was recently signed by thousands of tech industry employees, AI experts, and other interested parties calling for a six-month worldwide pause in AI development activity so that safety protocols can be developed. One prominent researcher in machine intelligence, Eliezer Yudkowsky, goes much further: he believes that avoiding human extinction requires immediate worldwide limits on resources dedicated to AI development. Is this a severely overwrought application of the precautionary principle? That’s a matter I’ll consider at greater length below, but like Caplan, I’m congenitally skeptical of claims of impending doom, whether from the mouth of Yudkowsky, Greta Thunberg, Paul Ehrlich, or Nassim Taleb.

As I mentioned at the top, I suspect competition among AI developers played a role in motivating some of the signatories of the “AI pause” letter, and some of the non-signatories as well. Robin Hanson points out that Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, did not sign the letter. OpenAI (controlled by a nonprofit foundation) owns ChatGPT and is the current leader in rolling out AI tools to the public. ChatGPT 4 can be used with the Microsoft search engine Bing, and Microsoft’s Bill Gates also did not sign the letter. Meanwhile, Google was caught flat-footed by the ChatGPT rollout, and its CEO signed. Elon Musk (who signed) wants to jump in with his own AI development: TruthGPT. Of course, the pause letter stirred up a number of members of Congress, which I suspect was the real intent. It’s reasonable to view the letter as a means of leveling the competitive landscape. Thus, it looks something like a classic rent-seeking maneuver, buttressed by the inevitable calls for regulation of AIs. However, I certainly don’t doubt that a number of signatories did so out of a sincere belief that the risks of AI must be dealt with before further development takes place.

The vast dimensions of the supposed AI “threat” may have some libertarians questioning their unequivocal opposition to public intervention. If so, they might just as well fear the potential that AI already holds for manipulation and control by central authorities in concert with their tech and media industry proxies. But realistically, broad compliance with any precautionary agreement between countries or institutions, should one ever be reached, is pretty unlikely. On that basis, a “scout’s honor” temporary moratorium or set of permanent restrictions might be comparable to something like the Paris Climate Accord. China and a few other nations are unlikely to honor the agreement, and we really won’t know whether they’re going along with it except for any traceable artifacts their models might leave in their wake. So we’ll have to hope that safeguards can be identified and implemented broadly.

Likewise, efforts to regulate by individual nations are likely to fail, and for similar reasons. One cannot count on other powers to enforce the same kinds of rules, or any rules at all. Putting our faith in that kind of cooperation with countries who are otherwise hostile is a prescription for ceding them an advantage in AI development and deployment. Regulation of the evolution of AI will likely fail. As Robert Louis Stevenson once wrote, “Thus paternal laws are made, thus they are evaded”. And if it “succeeds, it will leave us with a technology that will fall short of its potential to benefit consumers and society at large. That, unfortunately, is usually the nature of state intrusion into a process of innovation, especially when devised by a cadre of politicians with little expertise in the area.

Again, according to experts like Yudkowsky, AGI would pose serious risks. He thinks the AI Pause letter falls far short of what’s needed. For this reason, there’s been much discussion of somehow achieving an alignment between the interests of humanity and the objectives of AIs. Here is a good discussion by Seth Herd on the LessWrong blog about the difficulties of alignment issues.

Some experts feel that alignment is an impossibility, and that there are ways to “live and thrive” with unalignment (and see here). Alignment might also be achieved through incentives for AIs. Those are all hopeful opinions. Others insist that these models still have a long way to go before they become a serious threat. More on that below. Of course, the models do have their shortcomings, and current models get easily off-track into indeterminacy when attempting to optimize toward an objective.

But there’s an obvious question that hasn’t been answered in full: what exactly are all these risks? As Tyler Cowen has said, it appears that no one has comprehensively catalogued the risks or specified precise mechanisms through which those risks would present. In fact, AGI is such a conundrum that it might be impossible to know precisely what threats we’ll face. But even now, with deployment of AIs still in its infancy, it’s easy to see a few transition problems on the horizon.

White Collar Wipeout

Job losses seem like a rather mundane outcome relative to extinction. Those losses might come quickly, particularly among white collar workers like programmers, attorneys, accountants, and a variety of administrative staffers. According to a survey of 1,000 businesses conducted in February:

“Forty-eight percent of companies have replaced workers with ChatGPT since it became available in November of last year. … When asked if ChatGPT will lead to any workers being laid off by the end of 2023, 33% of business leaders say ‘definitely,’ while 26% say ‘probably.’ … Within 5 years, 63% of business leaders say ChatGPT will ‘definitely’ (32%) or ‘probably’ (31%) lead to workers being laid off.”

A rapid rate of adoption could well lead to widespread unemployment and even social upheaval. For perspective, that implies a much more rapid rate of technological diffusion than we’ve ever witnessed, so this outcome is viewed with skepticism in some quarters. But in fact, the early adoption phase of AI models is proceeding rather quickly. You can use ChatGPT 4 easily enough on the Bing platform right now!

Contrary to the doomsayers, AI will not just enhance human productivity. Like all new technologies, it will lead to opportunities for human actors that are as yet unforeseen. AI is likely to identify better ways for humans to do many things, or do wonderful things that are now unimagined. At a minimum, however, the transition will be disruptive for a large number of workers, and it will take some time for new opportunities and roles for humans to come to fruition.

Robin Hanson has a unique proposal for meeting the kind of challenge faced by white collar workers vulnerable to displacement by AI, or for blue collar workers who are vulnerable to displacement by robots (the deployment of which has been hastened by minimum wage and living wage activism). This treatment of Hanson’s idea will be inadequate, but he suggests a kind of insurance or contract sold to both workers and investors by owners of assets likely to be insensitive to AI risks. The underlying assets are paid out to workers if automation causes some defined aggregate level of job loss. Otherwise, the assets are paid out to investors taking the other side of the bet. Workers could buy these contracts themselves, or employers could do so on their workers’ behalf. The prices of the contracts would be determined by a market assessment of the probability of the defined job loss “event”. Governmental units could buy the assets for their citizens, for that matter. The “worker contracts” would be cheap if the probability of the job-loss event is low. Sounds far-fetched, but perhaps the idea is itself an entrepreneurial opportunity for creative players in the financial industry.

The threat of job losses to AI has also given new energy to advocates of widespread adoption of universal basic income payments by government. Hanson’s solution is far preferable to government dependence, but perhaps the state could serve as an enabler or conduit through which workers could acquire AI and non-AI capital.

Human Capital

Current incarnations of AI are not just a threat to employment. One might add the prospect that heavy reliance on AI could undermine the future education and critical thinking skills of the general population. Essentially allowing machines to do all the thinking, research, and planning won’t inure to the cognitive strength of the human race, especially over several generations. Already people suffer from an inability to perform what were once considered basic life skills, to say nothing of tasks that were fundamental to survival in the not too distant past. In other words, AI could exaggerate a process of “dumbing down” the populace, a rather undesirable prospect.

Fraud and Privacy

AI is responsible for still more disruptions already taking place, in particular violations of privacy, security, and trust. For example, a company called Clearview AI has scraped 30 billion photos from social media and used them to create what its CEO proudly calls a “perpetual police lineup”, which it has provided for the convenience of law enforcement and security agencies.

AI is also a threat to encryption in securing data and systems. Conceivably, AI could be of value in perpetrating identity theft and other kinds of fraud, but it can also be of value in preventing them. AI is also a potential source of misleading information. It is often biased, reflecting specific portions of the on-line terrain upon which it is trained, including skewed model weights applied to information reflecting particular points of view. Furthermore, misinformation can be spread by AIs via “synthetic media” and the propagation of “fake news”. These are fairly clear and present threats of social, economic, and political manipulation. They are all foreseeable dangers posed by AI in the hands of bad actors, and I would include certain nudge-happy and politically-motivated players in that last category.

The Sky-Already-Fell Crowd

Certain ethicists with extensive experience in AI have condemned the signatories of the “Pause Letter” for a focus on “longtermism”, or risks as yet hypothetical, rather than the dangers and wrongs attributable to AIs that are already extant: TechCrunch quotes a rebuke penned by some of these dissenting ethicists to supporters of the “Pause Letter”:

“‘Those hypothetical risks are the focus of a dangerous ideology called longtermism that ignores the actual harms resulting from the deployment of AI systems today,’ they wrote, citing worker exploitation, data theft, synthetic media that props up existing power structures and the further concentration of those power structures in fewer hands.”

So these ethicists bemoan AI’s presumed contribution to the strength and concentration of “existing power structures”. In that, I detect just a whiff of distaste for private initiative and private rewards, or perhaps against the sovereign power of states to allow a laissez faire approach to AI development (or to actively sponsor it). I have trouble taking this “rebuke” too seriously, but it will be fruitless in any case. Some form of cooperation between AI developers on safety protocols might be well advised, but competing interests also serve as a check on bad actors, and it could bring us better solutions as other dilemmas posed by AI reveal themselves.

Imagining AI Catastrophes

What are the more consequential (and completely hypothetical) risks feared by the “pausers” and “stoppers”. Some might have to do with the possibility of widespread social upheaval and ultimately mayhem caused by some of the “mundane” risks described above. But the most noteworthy warnings are existential: the end of the human race! How might this occur when AGI is something confined to computers? Just how does the supposed destructive power of AGIs get “outside the box”? It must do so either by tricking us into doing something stupid, hacking into dangerous systems (including AI weapons systems or other robotics), and/or through the direction and assistance of bad human actors. Perhaps all three!

The first question is this: why would an AGI do anything so destructive? No matter how much we might like to anthropomorphize an “intelligent” machine, it would still be a machine. It really wouldn’t like or dislike humanity. What it would do, however, is act on its objectives. It would seek to optimize a series of objective functions toward achieving a goal or a set of goals it is given. Hence the role for bad actors. Let’s face it, there are suicidal people who might like nothing more than to take the whole world with them.

Otherwise, if humanity happens to be an obstruction to solving an AGI’s objective, then we’d have a very big problem. Humanity could be an aid to solving an AGI’s optimization problem in ways that are dangerous. As Yudkowsky says, we might represent mere “atoms it could use somewhere else.” And if an autonomous AGI were capable of setting it’s own objectives, without alignment, the danger would be greatly magnified. An example might be the goal of reducing carbon emissions to pre-industrial levels. How aggressively would an AGI act in pursuit of that goal? Would killing most humans contribute to the achievement of that goal?

Here’s one that might seem far-fetched, but the imagination runs wild: some individuals might be so taken with the power of vastly intelligent AGI as to make it an object of worship. Such an “AGI God” might be able to convert a sufficient number of human disciples to perpetrate deadly mischief on its behalf. Metaphorically speaking, the disciples might be persuaded to deliver poison kool-aid worldwide before gulping it down themselves in a Jim Jones style mass suicide. Or perhaps the devoted will survive to live in a new world mono-theocracy. Of course, these human disciples would be able to assist the “AGI God” in any number of destructive ways. And when brain-wave translation comes to fruition, they better watch out. Only the truly devoted will survive.

An AGI would be able to create the illusion of emergency, such as a nuclear launch by an adversary nation. In fact, two or many adversary nations might each be fooled into taking actions that would assure mutual destruction and a nuclear winter. If safeguards such as human intermediaries were required to authorize strikes, it might still be possible for an AGI to fool those humans. And there is no guarantee that all parties to such a manufactured conflict could be counted upon to have adequate safeguards, even if some did.

Yudkowsky offers at least one fairly concrete example of existential AGI risk:

“A sufficiently intelligent AI won’t stay confined to computers for long. In today’s world you can email DNA strings to laboratories that will produce proteins on demand, allowing an AI initially confined to the internet to build artificial life forms or bootstrap straight to postbiological molecular manufacturing.”

There are many types of physical infrastructure or systems that an AGI could conceivably compromise, especially with the aid of machinery like robots or drones to which it could pass instructions. Safeguards at nuclear power plants could be disabled before steps to trigger melt down. Water systems, rivers, and bodies of water could be poisoned. The same is true of food sources, or even the air we breathe. In any case, complete social disarray might lead to a situation in which food supply chains become completely dysfunctional. So, a super-intelligence could probably devise plenty of “imaginative” ways to rid the earth of human beings.

Back To Earth

Is all this concern overblown? Many think so. Bryan Caplan now has a $500 bet with Eliezer Yudkowsky that AI will not exterminate the human race by 2030. He’s already paid Yudkowsky, who will pay him $1,000 if we survive. Robin Hanson says “Most AI Fear Is Future Fear”, and I’m inclined to agree with that assessment. In a way, I’m inclined to view the AI doomsters as highly sophisticated, change-fearing Luddites, but Luddites nevertheless.

Ben Hayum is very concerned about the dangers of AI, but writing at LessWrong, he recognizes some real technical barriers that must be overcome for recursive optimization to be successful. He also notes that the big AI developers are all highly focused on safety. Nevertheless, he says it might not take long before independent users are able to bootstrap their own plug-ins or modules on top of AI models to successfully optimize without running off the rails. Depending on the specified goals, he thinks that will be a scary development.

James Pethokoukis raises a point that hasn’t had enough recognition: successful innovations are usually dependent on other enablers, such as appropriate infrastructure and process adaptations. What this means is that AI, while making spectacular progress thus far, won’t have a tremendous impact on productivity for at least several years, nor will it pose a truly existential threat. The lag in the response of productivity growth would also limit the destructive potential of AGI in the near term, since installation of the “social plant” that a destructive AGI would require will take time. This also buys time for attempting to solve the AI alignment problem.

In another Robin Hanson piece, he expresses the view that the large institutions developing AI have a reputational Al stake and are liable for damages their AI’s might cause. He notes that they are monitoring and testing AIs in great detail, so he thinks the dangers are overblown.:

“So, the most likely AI scenario looks like lawful capitalism…. Many organizations supply many AIs and they are pushed by law and competition to get their AIs to behave in civil, lawful ways that give customers more of what they want compared to alternatives.”

In the longer term, the chief focus of the AI doomsters, Hanson is truly an AI optimist. He thinks AGIs will be “designed and evolved to think and act roughly like humans, in order to fit smoothly into our many roughly-human-shaped social roles.” Furthermore, he notes that AI owners will have strong incentives to monitor and “delimit” AI behavior that runs contrary to its intended purpose. Thus, a form of alignment is achieved by virtue of economic and legal incentives. In fact, Hanson believes the “foom” scenario is implausible because:

“… it stacks up too many unlikely assumptions in terms of our prior experiences with related systems. Very lumpy tech advances, techs that broadly improve abilities, and powerful techs that are long kept secret within one project are each quite rare. Making techs that meet all three criteria even more rare. In addition, it isn’t at all obvious that capable AIs naturally turn into agents, or that their values typically change radically as they grow. Finally, it seems quite unlikely that owners who heavily test and monitor their very profitable but powerful AIs would not even notice such radical changes.”

As smart as AGIs would be, Hanson asserts that the problem of AGI coordination with other AIs, robots, and systems would present insurmountable obstacles to a bloody “AI revolution”. This is broadly similar to Pethokoukis’ theme. Other AIs or AGIs are likely to have competing goals and “interests”. Conflicting objectives and competition of this kind will do much to keep AGIs honest and foil malign AGI behavior.

The kill switch is a favorite response of those who think AGI fears are exaggerated. Just shut down an AI if its behavior is at all aberrant, or if a user attempts to pair an AI model with instructions or code that might lead to a radical alteration in an AI’s level of agency. Kill switches would indeed be effective at heading off disaster if monitoring and control is incorruptible. This is the sort of idea that begs for a general solution, and one hopes that any advance of that nature will be shared broadly.

One final point about AI agency is whether autonomous AGIs might ever be treated as independent factors of production. Could they be imbued with self-ownership? Tyler Cowen asks whether an AGI created by a “parent” AGI could legitimately be considered an independent entity in law, economics, and society. And how should income “earned” by such an AGI be treated for tax purposes. I suspect it will be some time before AIs, including AIs in a lineage, are treated separately from their “controlling” human or corporate entities. Nevertheless, as Cowen says, the design of incentives and tax treatment of AI’s might hold some promise for achieving a form of alignment.

Letting It Roll

There’s plenty of time for solutions to the AGI threat to be worked out. As I write this, the consensus forecast for the advent of real AGI on the Metaculus online prediction platform is July 27, 2031. Granted, that’s more than a year sooner than it was 11 days ago, but it still allows plenty of time for advances in controlling and bounding agentic AI behavior. In the meantime, AI is presenting opportunities to enhance well being through areas like medicine, nutrition, farming practices, industrial practices, and productivity enhancement across a range of processes. Let’s not forego these opportunities. AI technology is far too promising to hamstring with a pause, moratoria, or ill-devised regulations. It’s also simply impossible to stop development work on a global scale.

Nevertheless, AI issues are complex for all private and public institutions. Without doubt, it will change our world. This AI Policy Guide from Mercatus is a helpful effort to lay out issues at a high-level.