Tags

Absolute Advantage, AGI, Andrew Mayne, Artificial General Intelligence, Comparative advantage, Dyson Spheres, Energy Demand, Fusion Reactors, Megastructures, Opportunity cost, Production Possibilities Curve, Reason Magazine, Reciprocality, Scarcity, Specialization, Super-Abundance

As of February 2026, I’m adding this short preamble to a few older posts on the subject of AI and future prospects for human labor. In the original post below (and a few others), I overstated the case that the law of comparative advantage would assure a continued role for humans in production. I still think the case is strong, mind you, but now I’m convinced that the outcome depends on elasticities of input substitution and how those elasticities might shift given the advent of AI-augmented capital. You can read my most recent thoughts on the matter here.

___________________________________________

You might know someone so smart and multi-talented that they are objectively better at everything than you. Let’s call him Harvey Specter. Harvey’s prospects on the labor market are very good. Economists would say he has an absolute advantage over you in every single pursuit! What a bummer! But obviously that doesn’t mean Harvey can or should do everything, while you do nothing.

Fears of Human Obsolescence

That’s the very situation many think awaits workers with the advent of artificial general intelligence (AGI), and especially with the marriage of AGI and advanced robotics (also see here). Any job a human can do, AGI or AGI robots of various kinds will be able to do better, faster, and in far greater quantity. The humanoid AGI robots will be like your talented acquaintance Harvey, but exponentiated. They won’t need much “sleep” or downtime, and treating wear and tear on their “health” will be a simple matter of replacing components. AGI and its robotic manifestations will have an absolute advantage in every possible endeavor.

But even with the existence of super-human AGI robots, I claim that work will be available to you if you want or need it. You won’t face the same set of pre-AGI opportunities, but there will be many opportunities for humans nonetheless. How can that be if AGI robots can do everything better? Won’t they be equipped to meet all of our material needs and wants?

Specter of the Super Productive

Let’s return to the example of you and Harvey, your uber-talented acquaintance. You’ll each have an area of specialization, but on what basis? Harvey has his pick of very lucrative and stimulating opportunities. You, however, are limited to a less dazzling array of prospects. There might be some overlap, and hard work or luck can make up for large differences, but chances are you’ll specialize in something that requires less talent than Harvey. You might wind up in the same profession, but Harvey will be a star.

Where will you end up? The answer is you and Harvey will find your respective areas of specialization based on comparative advantages, not absolute advantages. Relative opportunity cost is the key here, or its inverse: how much do you expect to gain from a certain area of specialization relative to the rewards you must forego.

For example, Harvey doesn’t sacrifice much by shunning less challenging areas of specialization. That is, he faces a low opportunity cost, while his chosen area offers great rewards for his talent.

You, on the other hand, might not have much to gain in Harvey’s line of work, if you can get it. You might be a flop if you do! Realistically, you forego very little if you instead pursue more achievable success in a less daunting area. You’ll be better off choosing an option for which your relative gains are highest, or said differently, where your relative opportunity cost is low.

A Quick Illustration

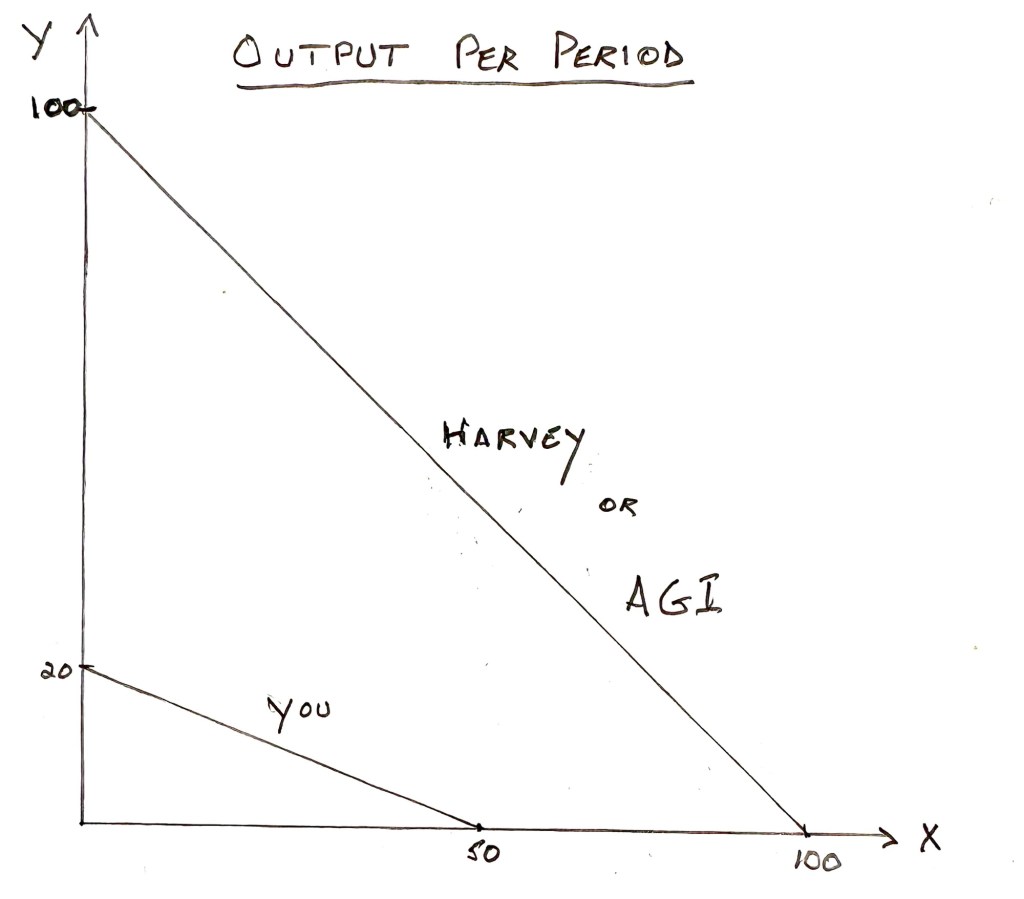

If you’re unwilling to slog through a simple numerical example, skip this section and the graph below. The graph was produced the old fashioned way: by a human being with a pencil, paper, ruler, and smart phone camera.

Here goes: Harvey can produce up to 100 units of X per period or 100 units of Y, or some linear combination of the two. Harvey’s opportunity costs are constant along this tradeoff between X and Y because it’s a straight line. It costs him one unit of Y output to produce every additional unit of X, and vice versa.

You, on the other hand, cannot produce X or Y as well as Harvey in an absolute sense. At most, you can produce up to 50 units of X per period, 20 units of Y, or some combination of the two along your own constant cost (straight line) tradeoff. You sacrifice 5/2 = 2.5 units of X to produce each unit of Y, so Harvey has the lower opportunity cost and a comparative advantage for Y. But it only costs you 2/5 = 0.4 units of Y to produce each additional unit of X, so you have a comparative advantage over Harvey in X production.

Reciprocal Advantages

In the end, you and Harvey specialize in the respective areas for which each has their lowest relative opportunity cost and a comparative advantage. If he has a comparative advantage in one area of production, and unless your respective tradeoffs have identical slopes (unlikely), the reciprocal nature of opportunity costs dictates that you have a comparative advantage in the other area of production.

Obviously, Harvey’s formidable absolute advantage over you in everything doesn’t impinge on these choices. In the real world, of course, comparative advantages play out across many dimensions of output, but the principle is the same. And once we specialize, we can trade with one another to mutual advantage.

No Such Thing As a Free AGI Robot

That brings us back to AGI and AGI robots. Like Harvey, they might well have an absolute advantage in every area of specialization, or they can learn quickly to achieve such an advantage, but that doesn’t mean they should do everything!

Just as in times preceding earlier technological breakthroughs, we cannot even imagine the types of jobs that will dominate the human and AGI work forces in the future. We already see complementarity between humans and AGI in many applications. AGI makes those workers much more productive, which leads to higher wages.

However, substitution of AGIs for human labor is a dominant theme of the many AGI “harm” narratives. In fact, substitution is already a reality in many occupations, like coding, and substitution is likely to broaden and intensify as the marriage of AGI and robotics gains speed. But that will occur only in industries for which the relative opportunity costs of AGIs, including all of the ancillary resources needed to produce them, are favorable. Among other things, AGI will require a gigantic expansion in energy production and infrastructure, which necessitates a massive exploitation of resources. Relative opportunity costs in the use of these resources will not always favor the dominance of AGIs in production. Like Harvey, AGIs and their ancillary resources cannot do everything because they cannot have comparative advantages without reciprocal comparative disadvantages.

Super-Abundance vs. Scarcity

Some might insist that AGIs will lead to such great prosperity that humans will no longer need to work. All of our material wants will be met in a new age of super-abundance. Despite the foregoing, that might suggest to some that AGIs will do everything! But here I make another claim: our future demands on resources will not be satisfied by whatever abundance AGIs make possible. We will still want to do more, whether we choose to construct fusion reactors, megastructures in space (like Dyson spheres or ring worlds), terraform Mars, undertake interstellar travel, perfect asteroid defense, battle disease, extend longevity, or improve our lives in ways now imagined or unimagined.

As a result, scarcity will remain a major force. To that extent, resources will have competing uses, they will face opportunity costs, and they will have comparative advantages vis a vis alternative uses to which they can be put. Scarcity is a reality that governs opportunity costs, and that means humans will always have roles to play in production.

Concluding Remarks

I wrote about human comparative advantages once before, about seven years ago. I think I was groping along the right path. The only other article I’ve seen to explicitly mention a comparative advantage of human labor vs. AGIs in the correct context is by Andrew Mayne in the most recent issue of Reason Magazine. It’s almost a passing reference, but it deserves more because it is foundational.

Harvey Specter shouldn’t occupy his scarce time performing tasks that compromise his ability to deliver his most rewarding services. Likewise, before long it will become apparent that highly productive AGI assets, and the resources required to build and operate them, should not be tied up in activities that humans can perform at lesser sacrifice. That’s a long way of saying that humans will still have productive roles to play, even when AGI achieves an absolute advantage in everything. Some of the roles played by humans will be complimentary to AGIs in production, but human labor will also be valuable as a substitute for AGI assets in other applications. As long as AGI assets have any comparative advantages, humans will have reciprocal comparative advantages as well.