Tags

AMD, central planning, CHIPS Act, Corporatism, Don Boudreaux, Donald Trump, Extortion, fascism, Golden Share, Howard Lutnick, Intel, MP Materials, National Security, Nippon Steel, NVIDIA, Protectionism, Public debt, Scott Bessent, Socialism, Tad DeHaven, TikTok, U.S. Steel, Unfunded Obligations, Veronique de Rugy

Since his inauguration, Donald Trump has been busy finding ways for the government to extort payments and ownership shares from private companies. This has taken a variety of forms. Tad DeHaven summarizes the major pieces of booty extracted thus far in the following bullet points (skipping the quote marks here):

- June 13: Trump issues an executive order allowing the Nippon Steel-US Steel deal contingent on giving the government a “golden share” that enables the president to exert extensive control over US Steel’s operations.

- July 10: The Department of Defense (DoD) unveils a multi-part package with convertible preferred stock, warrants, and loan guarantees, making it the top shareholder of rare earth metals producer MP Materials.

- July 23: The White House claims an agreement with Japan to reduce the president’s so-called reciprocal tariff rate on Japanese imports comes with a $550 billion Japanese “investment fund” that Trump will control.

- July 31: Trump claims an agreement with South Korea to reduce the so-called reciprocal tariff on South Korean imports comes with a $350 billion South Korean-financed investment in projects “owned and controlled by the United States” that he will select.

- August 11: The White House confirms an “unprecedented” deal with Nvidia and AMD that allows them to sell particular chips to China in exchange for 15 percent of the sales.

- August 12: In a Fox Business interview, Bessent points to the alleged investments from Japan, South Korea, and the EU “to some extent” and says, “Other countries, in essence, are providing us with a sovereign wealth fund.”

- August 22: Fifteen days after calling for Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan to resign, Trump announces that the US will take a 10 percent equity stake in Intel using the CHIPS Act and DoD funds, becoming Intel’s largest single shareholder.

Each of these “deals” has a slightly different back story, but national security is a common theme. And Trump says they’ll all make America great again. They are touted as a way for American taxpayers to benefit from the investment he claims his policies are attracting to the U.S. However, all of these are ill-advised for several reasons, some of which are common to all. That includes the extortionary nature of each and every one of them.

Short Background On “Deals”

The June 13 deal (Nippon/US Steel), the July 10 deal (MP Materials), and the August 22 deal (Intel) all involve U.S. government equity stakes in private companies. The August 11 deal (NVIDIA/AMD) diverts a stream of private revenue to the government. The July 23 and July 31 deals (Japan and South Korea) both involve “investment funds” that Trump will control to one extent or another.

The August 12 entry adds “expected” EU investments with some qualification, but that bullet quotes Treasury Secretary Bessent referring to these investments as part of a sovereign wealth fund (SWF). Secretary of Commerce Lutnick now denies that an SWF will exist. My objections might be tempered slightly (but only slightly) by an SWF because it would probably need to place constraints on an Administation’s control. That might give you a hint as to why Lutnick is now downplaying the creation of an SWF.

I object to the Nippon/US Steel “deal” in part (and only in part) because it was extortion on its face. There is no valid anti-trust argument against the deal (US Steel is the nation’s third largest steelmaker and is broke), and the national security concerns that were voiced (Japan! for one thing) were completely bogus. Even worse, the “Golden Share” would give the federal government authority, if it chose to exercise it, over a variety of the company’s decisions.

The Intel “deal” is another highly questionable transaction. Intel was to receive $11 billion under the CHIPS Act, a fine example of corporate welfare, as Veronique de Rugy once described the law. However, Intel was to receive its grants only if it stood up four fabrication facilities. But it did not. Now, instead of demanding reimbursement of amounts already paid, the government offered to pay the remainder in exchange for a 9.9% stake in the company. And there is no apparent requirement that Intel meet the original committment! This could turn out a bust!

The MP Materials transaction with the Department of Defense has also been rationalized on national security grounds. This excuse comes a little closer to passing the smell test, but the equity stake is objectionable for other reasons (to follow).

The Nvidia/AMD deal has been justified as compensation for allowing the companies to sell chips to China, which is competing with the U.S. to lead the world in AI development. This is another form of selective treatment, here applied to an export license. The chips in question do not have the same advanced specifications as those sold by the companies in the U.S., but let’s not let that get in the way of a revenue opportunity.

While nothing about TikTok appears on the list above, I fear that a resolution of its operational status in the U.S. presents another opportunity for extortion by the Trump Administration. I’m sure there will be many other cases.

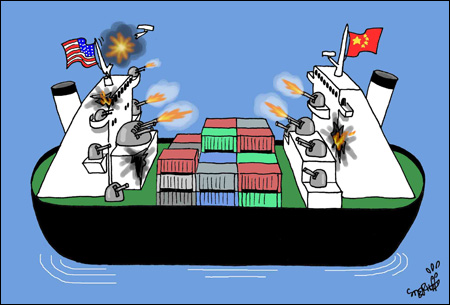

Root Cause: Protectionism

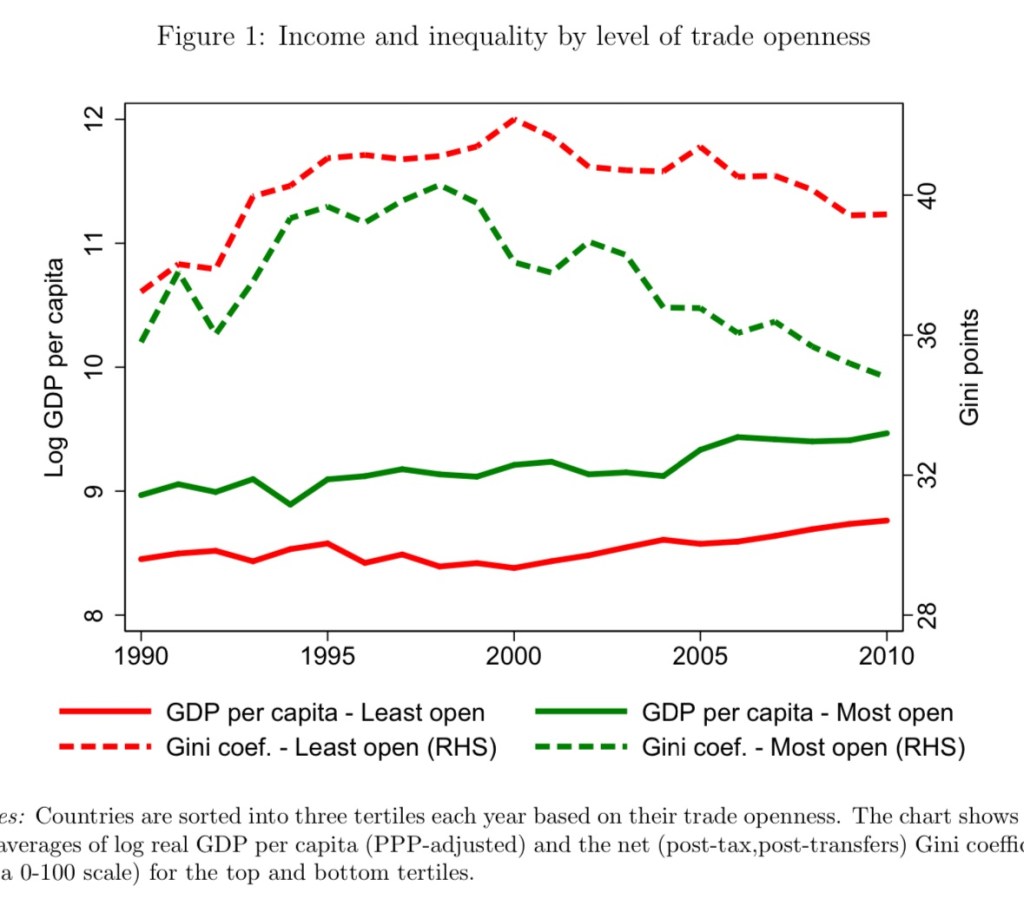

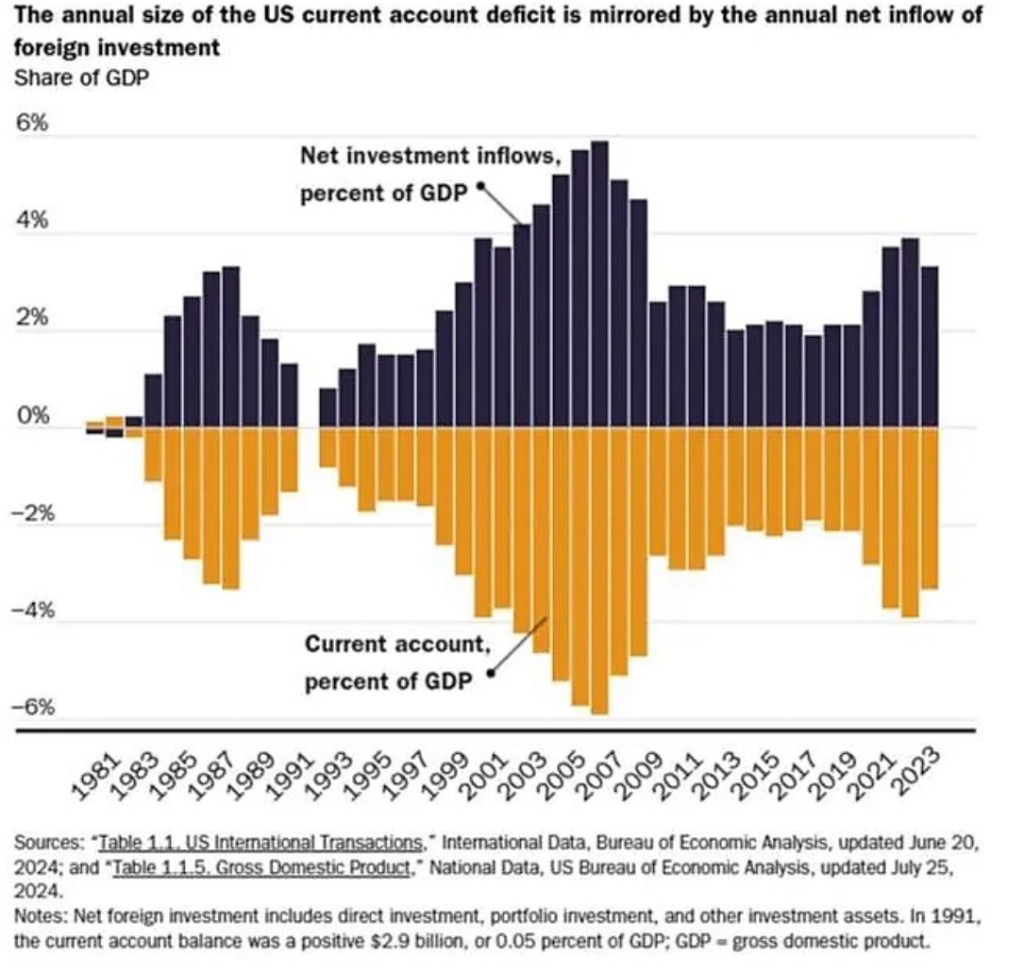

The so-called investment funds described in the timeline above are nearly all the result of trade terms negotiated by a dominant and belligerent trading partner: the U.S. My objections to tariffs are one thing, but here we are extorting investment pledges for reductions in the taxes we’ll impose on our own citizens! Additionally, the belief that these investments will somehow prevent a general withdrawal of foreign investment in the U.S. is misguided. In fact, a smaller trade deficit dictates less foreign investment. The difference here is that the government will wrest ownership control over a greater share of less foreign investment.

Trump the Socialist?

Needless to say, I don’t favor government ownership of the means of production. That’s socialism, but do matters of national security offer a rationale for public ownership? For example, rare earth minerals are important to national defense. Therefore, it’s said that we must ensure a domestic supply of those minerals. I’m not convinced that’s true, but in any case, fat defense contracts should create fat profit opportunities in mining rare earths (enter MP Materials). None of that means public ownership is necessary or a good idea.

All of these federal investments are construed, to one extent or another, as matters of national security, but that argument for market intervention is much too malleable. Must we ensure a domestic supply of semiconductors for national security reasons? And public ownership? Is the same true of steel? Is the same true of our “manufacturing security”? It can go on and on. The next thing you know, someone will argue that grocery stores should be owned by the government in the name of “food security”! Oh, wait…

Trump the Central Planner

Government ownership takes the notion of industrial planning a huge step beyond the usual conception of that term. Ordinarily, when government takes the role of encouraging or discouraging activity in particular industries or technologies, it attempts to select winners and losers. The very idea presumes that the market is not allocating resources in an optimal way, as if the government is in any position to gainsay the decisions of private market participants who have skin in the game. This is a foolhardy position with predictably negative consequences. (For some examples, see the first, second, and fourth articles linked here by Don Boudreaux.) The fundamental flaw in central planning always comes down to the inability of planners to collect, process, and act on the information that the market handles with marvelous efficiency.

When government invests taxpayer funds in exchange for ownership positions in private concerns, the potential levers of control are multiplied. One danger is that political guidance will replace normal market incentives. And as de Rugy points out, the government’s potential role as a regulator creates a clear conflict of interest. In a strong sense, a government ownership stake is worse for private owners than a mere dilution of their interests. It looms as a possible taking, as private owners and managers surrender to creeping government extortion.

Financial Malfeasance

In addition to the objections above, I maintain that these investments represent poor stewardship of public funds. The U.S. public debt currently stands at $37 trillion with an entitlement disaster still to come. In fact, according to one estimate, the federal government’s total unfunded obligations amount to additional $121 trillion! Putting aside the extortion we’re witnessing, any spare dollar should be put toward retiring debt, rather than allowing its upward progression.

As I’ve noted before, paying off a dollar of debt entails a risk-free “return” in the form of interest cost avoidance, let’s say 3.5% for the sake of argument. If instead the dollar is “invested” in risk assets by the government, the interest cost is still incurred. To earn a net return as high as the that foregone from interest avoidance, the government must consistently earn at least 7% on its invested dollar. But of course that return is not risk-free!

A continuing failure to pay down the public debt will ultimately poison the debt market’s assessment of the government’s will to stay within its long-run budget constraint. That would ultimately manifest in an inflation, shrinking the real value of the public debt even as it undermines the living standards of many Americans.

One final thought: Though few MAGA enthusiasts would admit it even if they understood, we’re witnessing a bridging of two ends of the idealogical “horseshoe”. Right-wing populism and protectionism meet the left-wing ideal of central planning and public ownership. There is a name for this particular form of corporatist state, and it is fascism.