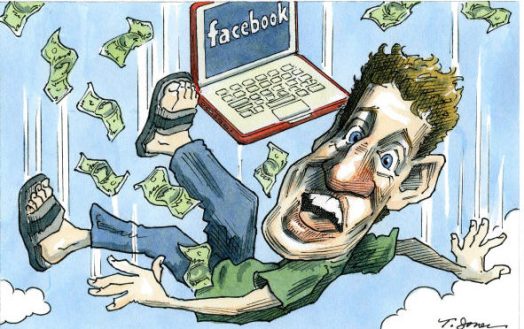

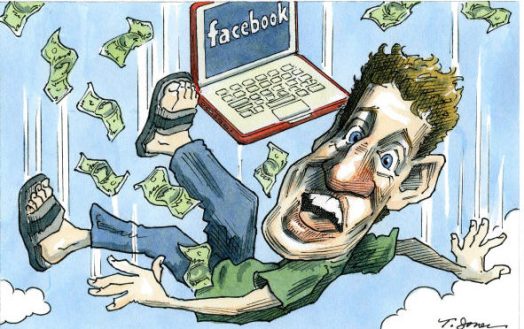

Facebook is under fire for weak privacy protections, its exploitation of users’ data, and the dangers it is said to pose to Americans’ free speech rights. Last week, Mark Zuckerberg, who controls all of the voting stock in Facebook, attempted to address those issues before a joint hearing of the Senate Judiciary and Commerce Committees. It represented a major event in the history of the social media company, and it happened at a time when discussion of antitrust action against social media conglomerates like Facebook, Google, and Amazon is gaining support in some quarters. I hope this intervention does not come to pass.

The Threat

At the heart of the current uproar are Facebook’s data privacy policy and a significant data breach. The recent scandal involving Cambridge Analytica arose because Facebook, at one time, allowed application developers to access user data, and the practice continued for a few developers. Unfortunately, at least one didn’t keep the data to himself. There have been accusations that the company has violated privacy laws in the European Union (EU) and privacy laws in some states. Facebook has also raised ire among privacy advocates by lobbying against stronger privacy laws in some states, but it is within its legal rights to do so. Violations of privacy laws must be adjudicated, but antitrust laws were not intended to address such a threat. Rather, they were intended to prevent dominant producers from monopolizing or restraining trade in a market and harming consumers in the process.

Matt Stoller, in an interview with Russ Roberts on EconTalk, says antitrust action against social media companies may be necessary because they are so pervasive in our lives, have built such dominant market positions, and have made a practice of buying nascent competitors over the years. Steps must be taken to “oxygenate” the market, according to Stoller, promoting competition and protecting new entrants.

Tim Wu, the attorney who coined the misleading term “network neutrality”, is a critic of Facebook, though Wu is more skeptical of the promise of antitrust or regulatory action:

“In Facebook’s case, we are not speaking of a few missteps here and there, the misbehavior of a few aberrant employees. The problems are central and structural, the predicted consequences of its business model. From the day it first sought revenue, Facebook prioritized growth over any other possible goal, maximizing the harvest of data and human attention. Its promises to investors have demanded an ever-improving ability to spy on and manipulate large populations of people. Facebook, at its core, is a surveillance machine, and to expect that to change is misplaced optimism.”

Google has already been subject to antitrust action in the EU due to the alleged anti-competitive nature of its search algorithm, and Facebook’s data privacy policy is under fire there. But the prospect of traditional antitrust action against a social media company like Facebook seems rather odd, as acknowledged by the author at the first link above, Navneet Alang:

“… Facebook specifically doesn’t appear to be doing anything that actively violates traditional antitrust rules. Instead, it’s relying on network effects, that tendency of digital networks to have their own kind of inertia where the more people get on them the more incentive there is to stay. It’s also hard to suggest that Facebook has a monopoly on advertising dollars when Google is also raking in billions of dollars.“

Competition

The size of Facebook’s user base gives it a massive advantage over most of the other platforms in terms of network effects. I offer myself as an example of the inertia described by Alang: I’ve been on Facebook for a number of years. I use it to keep in touch with friends and as a vehicle for attracting readers to my blog. As I contemplated this post, I experimented by opening a MeWe account, where I joined a few user groups. It has a different “feel” than Facebook and is more oriented toward group chats. I like it and I have probably spent as much time on MeWe in the last week as Facebook. I sent MeWe invitations to about 20 of my friends, nearly all of whom have Facebook accounts, and a few days later I posted a link to MeWe on my Facebook wall. Thus far, however, only three of my friends have joined MeWe. Of course, none of us has deactivated our Facebook account, and I speculate that none of us will any time soon. This behavior is consistent with “platform inertia” described by Alang. Facebook users are largely a captive market.

But Facebook is not a monopoly and it is not a necessity. Neither is Google. Neither is Amazon. All of these firms have direct competitors for both users and advertising dollars. It’s been falsely claimed that Google and Facebook together control 90% of online ad revenue, but the correct figure for 2017 is estimated at less than 57%. That’s down a bit from 2016, and another decline is expected in 2018. There are many social media platforms. Zuckerberg claims that the average American already uses eight different platforms, which may include Facebook, Google+, Instagram, LinkedIn, MeWe, Reddit, Spotify, Tinder, Tumblr, Twitter, and many others (also see here). Some of these serve specialized interests such as professional networking, older adults, hook-ups, and shopping. Significant alternatives for users exist, some offering privacy protections that might have more appeal now than ever.

Antitrust vs. Popular, Low-Priced Service Providers

Facebook’s business model does not fit comfortably into the domain of traditional antitrust policy. The company’s users pay a price, but one that is not easily calculated or even perceived: the value of the personal data they give away on a daily basis. Facebook is monetizing that data by allowing advertisers to target individuals who meet specific criteria. Needless to say, many observers are uncomfortable with the arrangement. The company must maintain a position of trust among its users befitting such a sensitive role. No doubt many have given Facebook access to their data out of ignorance of the full consequences of their sacrifice. Many others have done so voluntarily and with full awareness. Perhaps they view participation in social media to be worth such a price. It is also plausible that users benefit from the kind of targeted advertising that Facebook facilitates.

Does Facebook’s business model allow it to engage in an ongoing practice of predatory pricing? It is far from clear that its pricing qualifies as “anti-competitive behavior”, and courts have been difficult to persuade that low prices run afoul of U.S. antitrust law:

“Predatory pricing occurs when companies price their products or services below cost with the purpose of removing competitors from the market. … the courts use a two part test to determine whether they have occurred: (1) the violating company’s production costs must be higher than the market price of the good or service and (2) there must be a ‘dangerous probability’ that the violating company will recover the loss …”

Applying this test to Facebook is troublesome because as we have seen, users exchange something of value for their use of the platform, which Facebook then exploits to cover costs quite easily. Fee-based competitors who might complain that Facebook’s pricing is “unfair” would be better-advised to preach the benefits of privacy and data control, and some of them do just that as part of their value proposition.

More Antitrust Skepticism

John O. McGinnis praises the judicial restraint that has characterized antitrust law over the past 30 years. This practice recognizes that it is not always a good thing for consumers when the government denies a merger, for example, or busts up a firm deemed by authorities to possess “too much power”. An innovative firm might well bring new value to its products by integrating them with features possessed by another firm’s products. Or a growing firm may be able to create economies of scale and scope that are passed along to consumers. Antitrust action, however, too often presumes that a larger market share, however defined, is unequivocally bad beyond some point. Intervention on those grounds can have a chilling effect on innovation and on the value such firms bring to the market and to society.

There are more fundamental reasons to view antitrust enforcement skeptically. For one thing, a product market can be defined in various ways. The more specific the definition, the greater the appearance of market dominance by larger firms. Or worse, the availability of real alternatives is ignored. For example, would an airline be a monopolist if it were the only carrier serving a particular airport or market? In a narrow sense, yes, but that airline would not hold a monopoly over intercity transportation, for which many alternatives exist. Is an internet service provider (ISP) a monopoly if it is the only ISP offering a 400+ Mbs download speed in a certain vicinity? In a very narrow sense, yes, but there may be other ISPs offering slower speeds that most consumers view as adequate. And in all cases, consumers always have one very basic alternative: not buying. Even so-called natural monopolies, such as certain public utilities, offer services for which there are broad alternatives. In those cases, however, a grant of a monopoly franchise is typically seen as a good solution if exchanged for public oversight and regulation, so antitrust is generally not at issue.

One other basic objection that can be made to antitrust is that it violates private property rights. A business that enjoys market dominance usually gets that way by pleasing customers. It’s rewards for excellent performance are the rightful property of its owners, or should be. Antitrust action then becomes a form of confiscation by punishing such a firm and its owners for success.

Political Bias

Another major complaint against Facebook is political bias. It is accused of selectively censoring users and their content and manipulating user news feeds to favor particular points of view. Promises to employ fact-check mechanisms are of little comfort, since the concern involves matters of opinion. Any person or organization held to be in possession of the unadulterated truth on issues of public debate should be regarded with suspicion.

Last Tuesday at the joint session, Zuckerberg acted as if such a bias was quite natural, given that Facebook’s employee base is concentrated in the San Francisco Bay area. But his nonchalance over the matter partly reflects the fact that Facebook is, after all, a private company. It is free to host whatever views it chooses, and that freedom is for the better. Facebook is not like a public square. Instead, the scope of a user’s speech is largely discretionary: users select their own network of friends; they can choose to limit access to their posts to that group or to a broader group of “friends of friends”; they can limit posts to subgroups of friends; or they can allow the entire population of users to see their posts, if interested. No matter how many users it has, Facebook is still a private community. If its “community standards” or their enforcement are objectionable, then users can and should find alternative outlets. And again, as a private company, Facebook can choose to feature particular news sources and censor others without running afoul of the First Amendment.

Revisiting Facebook’s Business Model

The greatest immediate challenge for Facebook is data privacy. Trust among users has been eroded by the improprieties in Facebook’s exploitation of data. It’s as if everyone in the U.S. has suddenly awoken to the simple facts of its business model and the leveraging of user data it requires. But it is not of great concern to some users, who will be happy to continue to use the platform as they have in the past. Zuckerberg did not indicate a willingness to yield on the question of Facebook’s business model in his congressional testimony, but there is a threat that regulation will require steps to protect data that might be inconsistent with the business model. If users opt-out of data sharing in droves, then Facebook’s ability to collect revenue from advertisers will be diminished.

As Jonathan Zittrain points out, Facebook might find new opportunity as an information fiduciary for users. That would require a choice between paying a monthly fee or allowing Facebook to continue targeted advertising on one’s news feed. Geoffrey A. Fowler writes that the idea of paying for Facebook is not an outrageous proposition:

“Facebook collected $82 in advertising for each member in North America last year. Across the world, it’s about $20 per member. … Netflix costs $11 and Amazon Prime is $13 per month. Facebook would need $7 per month from everyone in North America to maintain its current revenue from targeted advertising.”

Given a choice, not everyone would choose to pay, and I doubt that a fee of $7 per month would cost Facebook much in terms of membership anyway. It could probably charge slightly more for regular memberships and price discriminate to attract students and seniors. Fowler contends that a user-paid Facebook would be a better product. It might sharpen the focus on user-provided and user-linked content, rather than content provided by advertisers. As Tim Wu says, “… payment better aligns the incentives of the platform with those of its users.” Fowler also asserts that regulatory headaches would be less likely for the social network because it would not be reliant on exploiting user data.

A noteworthy aspect of Zuckerberg’s testimony at the congressional hearing was his stated willingness to consider regulatory solutions: the “right regulations“, as he put it. That might cover any number of issues, including privacy and political advertising. But as Brendan Kirby warns, regulating Facebook might not be a great idea. Established incumbents are often capable of bending regulatory bodies to their will, ultimately using them to gain a stronger market position. A partnership between the data-rich Facebook and an agency of the government is not one that I’d particularly like to see. Tim Wu believes that what we really need are competitive alternatives to Facebook: he floats a few ideas about how a Facebook competitor might be structured, most prominently the fee-based alternative.

Let It Evolve

Like many others, I’m possessed by an anxiety about the security of my data on social media, an irritation with the political bias that pervades social media firms, and a suspicion that certain points of view are favored over others on their platforms. But I do not favor government intervention against these firms. Neither antitrust action nor regulation is likely to improve the available platforms or their services, and instead might do quite a bit of damage. “Trust-busting” of social media platforms would present technological challenges, but even worse, it would disrupt millions of complex relationships between firms and users and attempt to replace them with even more numerous and complex relationships, all dictated by central authorities rather than market forces. Significant mergers and acquisitions will continue to be reviewed by the DOJ and the FTC, preferably tempered by judicial restraint. I also oppose the regulatory option. Compliance is costly, of course, but even worse, the social media giants can afford it and will manipulate it. Those costs would inevitably present barriers to market entry by upstart competitors. The best regulation is imposed by customers, who should assert their sovereignty and exercise caution in the relationships they establish with social media platforms … and remember that nothing comes for free.