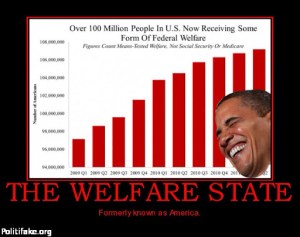

No one likes a monopoly except the monopolist, and a monopoly granted by patent is generally no exception. Patents are intended to be temporary, but they are often extended, at high cost to customers, beyond what many consider necessary as an incentive for innovation. There is also doubt about the validity of many “innovations” on which patents are issued. Alex Tabarrok once posted this cute illustration on the excesses of patent law. He has also discussed the existence of “patent thickets”, situations in which “a new product can require the use of hundreds or even thousands of previous patents, giving each patent owner veto-power over innovation“, or at least a way to skim some of the profits. Such thickets serve as a detriment to innovation, contribute to excessive litigation, and ultimately defeat the purpose of rewarding an innovator. Patent “trolls”, who threaten litigation over patent issues but may not own any patents themselves, have become a growing problem. In many ways, intellectual property laws begin to look like a rent-seeker’s playground. James Pethokoukas blogged late last year about a new study by the Congressional Budget Office stating that the U.S. patent system had “weakened the linkage between patenting and innovation“.

There is strong disagreement among libertarians about the validity of intellectual property rights (IP — copyrights, trademarks and patents). My natural sympathies are with the individual who rightfully seeks to benefit from their own creativity and hard work, but whether an innovator should enjoy a state-enforced monopoly on any and all applications of an idea is another matter. If potential competitors, customers and society have an obligation to this individual, some would insist that it is merely an ethical obligation, not one that should be sanctioned by the state.

In what follows, I will mostly refer to generic “ideas”, with the caveat that there are important distinctions between patents, trademarks and copyrights. I do not mean to minimize those distinctions. Rather, my interest lies in the general notion of intellectual property and any fundamental rights that successful “ideation” should confer. I confess that I have a bias in favor of rewarding innovators, but that might be a mere mental remnant of our legacy of IP protection in the U.S.

Suppose that some person, Mr. I, has an idea, and it is the first of its kind. Should Mr. I be granted an exclusive right to the idea and a monopoly on its application? Two qualities of tangible property are thought to be helpful in thinking about this kind of problem: rivalrousness and exclusivity. Rivalrous benefits make sharing difficult and make a thing more suitable as private property. Exclusivity means that others can be restricted from enjoying the benefits. If ideas had these qualities, then possession of an idea would settle the issue of rights without the need for special recognition of IP by government.

Pure public goods like air are non-rivalrous. Ideas themselves are often said to be non-rivalrous, but what is done with them might produce rivalrous benefits. If the benefits of Mr. I’s idea can be enjoyed by one individual without diminishing the benefits to others, then the idea is non-rivalrous.

Exclusivity is a closely-related but separate concept meaning that the benefits can be enjoyed privately, to the exclusion of others. Pure public goods lack both rivalrousness and exclusivity. On the other hand, a painting can be owned and kept in a private home, thus making it exclusive despite the fact that its benefits are largely non-rivalrous; though multiple individuals can enjoy a film simultaneously (non-rivalrous), it can be screened in a private venue charging admission; and while software can be shared, it is possible to achieve a measure of exclusivity by limiting the media (and replicability) through which it is available. However, the idea underlying a productive machine or process may be exclusive only to the extent that it cannot be discovered or reverse-engineered. While a new machine may be purchased from Mr. I and then owned and used exclusively, the idea itself has only limited exclusivity.

To strip the problem down to bare essentials, suppose there are no frictions in the transmission of information and that if Mr. I makes any practical use of his idea, or even mentions it to someone else, then the idea will be immediately known to all others. The idea itself is non-rivalrous and non-exclusive. There could still be gains to marketing applications if there are production costs involved (as that discourages entry), and those gains are rivalrous if the number of potential buyers is limited. To slightly rephrase the original question: Should Mr. I be granted, by the power of the state, an exclusive right and a monopoly on applications of his idea? A brilliant idea may have a rivalrous dimension and its benefits may be exclusive, but any non-exclusivity of the idea itself will diminish its market value. Does that offer sufficient grounds for the existence of IP?

This was essentially Eugene Volokh’s position when he asserted, in 2003, that a non-rivalrous good (water from the water table) has a market value, like any piece of tangible property, as long as it is possible to exclude others from access (to a well). (But that was not Volokh’s main argument in support of IP — see below.) Lawrence Solum at Legal Theory Blog took issue with Volokh’s position on valuation, insisting that it is often impossible to price IP optimally and therefore it is not like tangible property. Here is Volokh’s brief rejoinder, which rests partly on the argument discussed in the next paragraph.

A standard defense for IP is that rewarding invention and creativity enhances incentives for “great works” and technological advance. This was Volokh’s main defense of IP. Many libertarians find this hard to swallow, however. First, they insist that creative action is often driven by non-pecuniary motives. Nevertheless, art and invention are facilitated by funding, so the existence of IP rights may help to secure that support. A second objection is that ideas are frequently not unique; there are many examples of near-simultaneous discoveries. So, as this objection goes, if A hadn’t thought of it, B would have, and the incentive is often unnecessary. That is anything but absolute, however.

A very libertarian argument against property rights for ideas is that defining such a right infringes on the property rights of others. That is, any law restricting the use of an idea by others necessarily prevents them from using their own resources in a particular way. It therefore represents a kind of taking. This post by Stephan Kinsella at the Mises Daily stakes out this position:

“Patents grant rights in ‘inventions’ — useful machines or processes. They are grants by the state that permit the patentee to use the state’s court system to prohibit others from using their own property in certain ways — from reconfiguring their property according to a certain pattern or design described in the patent, or from using their property (including their own bodies) in a certain sequence of steps described in the patent.

In both cases, the state is assigning to A a right to control B’s property: A can tell B not to do certain things with it. Since ownership is the right to control, IP grants to A co-ownership of B’s property.“

Kinsella’s view is that creation, in and of itself, does not imply ownership. It is a transformation of resources, but ultimately the owner of those resources must own the creation. My difficulty with this argument is that an idea, if previously unknown to anyone, has no necessary impact on a prior use of resources owned by others. The ex ante value of those resources is based on their prior use, and that use can be continued. Certainly, if the new idea implies that the prior use is no longer the best use of those resources, then an patent-like restriction on the use of the new idea represents a harm. For example, if the new idea reduces production costs and an established competitor is restricted from using the idea, they will be harmed. Nevertheless, I hesitate to call this a “taking” because there is no restriction on the prior use.

Roderick T. Long makes the same argument as Kinsella in “The Libertarian Case Against Intellectual Property Rights“:

“... information is not a concrete thing an individual can control; it is a universal, existing in other people’s minds and other people’s property, and over these the originator has no legitimate sovereignty. You cannot own information without owning other people.“

Long makes the further claim that ownership of inventions embodying IP is not legitimate because one cannot own a “law of nature”:

“Defenders of patents claim that patent laws protect ownership only of inventions, not of discoveries. (Likewise, defenders of copyright claim that copyright laws protect only implementations of ideas, not the ideas themselves.) But this distinction is an artificial one. Laws of nature come in varying degrees of generality and specificity; if it is a law of nature that copper conducts electricity, it is no less a law of nature that this much copper, arranged in this configuration, with these other materials arranged so, makes a workable battery.“

I find this view preposterous. Nature exists apart from our ability to exploit it. A new piece of knowledge or practical technique is not itself a “law of nature”. It is a discovery about the laws of nature.

Here are Arnold Kling’s thoughts on these and other IP posts, including this short piece from Daniel Drezner, who discusses the importance of credible commitment in protecting rights. A credible commitment does not exist when ex ante assertions of IP protection prove to be malleable ex post, under pressure from critics pointing to the larger gains of rescinding those protections.

I was motivated to write about IP after reading a post by Jeffrey Tucker at the Beautiful Anarchy blog, who wrote about the severe handicaps imposed by government regulation on society. In that post, he briefly disparaged IP. Tucker noted the spooky similarity of the present regulatory environment to Ayn Rand’s novel Anthem. I agree, but there is some irony in this, as Rand herself was a strong supporter of IP rights. Here is what Tucker said about IP:

“Through intellectual property laws, the state literally assigned ownership to ideas that are the source of innovation, thereby restricting them and entangling entrepreneurs in endless litigation and confusion. Products are kept off the market. Firms that would come into existence do not. Profits that would be earned never appear. Intellectual property has institutionalized slow growth and landed the economy in a thicket of absurdity.“

The nation’s founders certainly wished to recognize IP rights, but only within limits. The so-called Copyright Clause in Article I of the U.S. Constitution empowers Congress:

“To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

So, like it or not, IP is recognized in the Constitution. The libertarian arguments against IP are persuasive in some respects, but I am not wholly convinced of their wisdom in terms of promoting innovation and economic growth. However, I am persuaded that shorter patent duration and severe limits on extensions would reward innovators and offer them incentives without the loss of growth implied by a long-term grant of monopoly. And this sort of modification might encourage more efforts to handle IP contractually, a topic that is discussed in detail (and with skepticism) in the post linked above from Long. There may be benefits as well to defining a higher threshold as to patentable ideas. For example, some say that only discoveries, not mere innovations, should be granted patents. “Mere” innovators could still capture gains via first-mover advantage and their own branding efforts, but not via patents.