Tags

Adolf Hitler, anti-Semitism, Banality of Evil, Bari Weiss, C.S. Lewis, Class Struggle, Critical Theory, David Foster, DEI, Diversity, Equity, Federalist Society, Gaza, Great Depression, Hamas, Inclusion, Inner Ring, Institutionalized Racism, Jamie Kirchick, Marxism, Naziism, Oppressors, Philip Carl Salzman, Protected Groups, Reverse Discrimination, Ricochet, Social Justice, Tablet, Weimar Republic, Zero-Sum Game

Germany’s inter-war descent into genocidal barbarism is perhaps the most horrifying episode of modern times. Seemingly normal, “nice people” in Germany were persuaded to go along with the murderous pogroms of the anti-Semitic National Socialists, giving truth to the “banality of evil”, as the famous expression goes. Of course, there were plenty of true believers, and multitudes bowed to the Nazis under fierce coercion, but many others went along just to “fit in”.

What could life have felt like in Weimar Germany in the late 1920s and early 1930s as the fascists accumulated power? Were normal people afraid? Well before Adolf Hitler’s rise to power he was known for his hatred of Jews, but German political leaders who enabled his ascent did not take his extreme prejudice as seriously as they should have, or they thought they could at least keep him and his followers in check. Surely there were people who foresaw the approaching cataclysm for what it would be.

Current expressions of anti-Semitism might give us a sense of what life was like during the decline and fall of the Weimar Republic. Just ask Jewish students at NYU and Cornell if they’ve sensed a whiff of it in the wake of Hamas’ slaughter of civilians in southern Israel on October 7th. The harassment these students have endured was motivated in part by claims that Israeli retaliation is morally inferior to the barbarities committed by Hamas, which is preposterous.

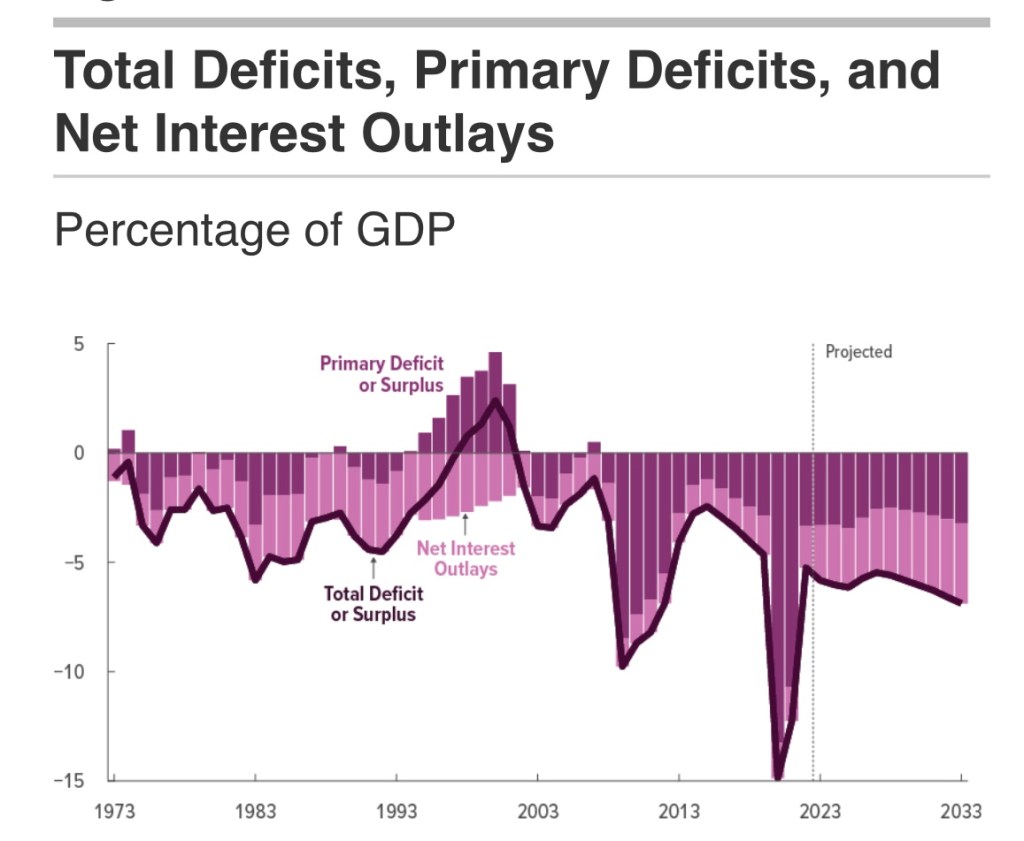

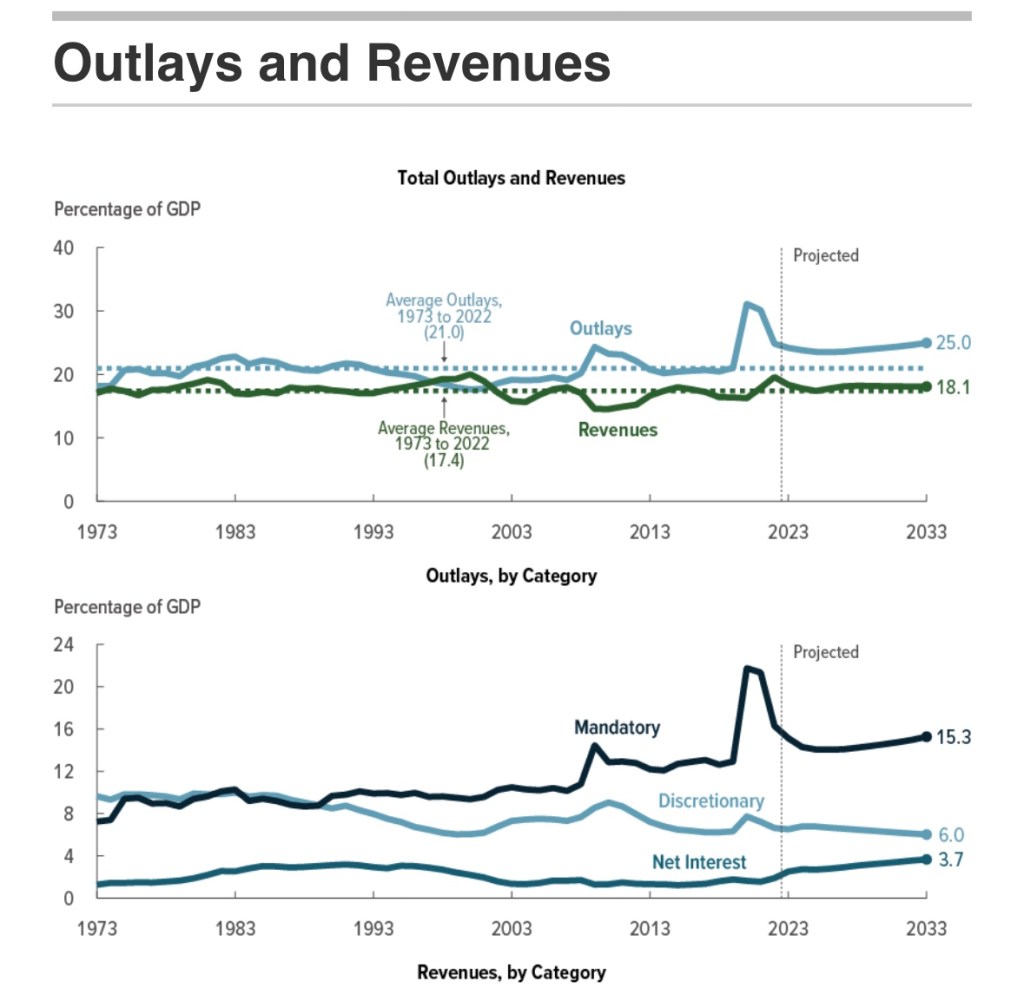

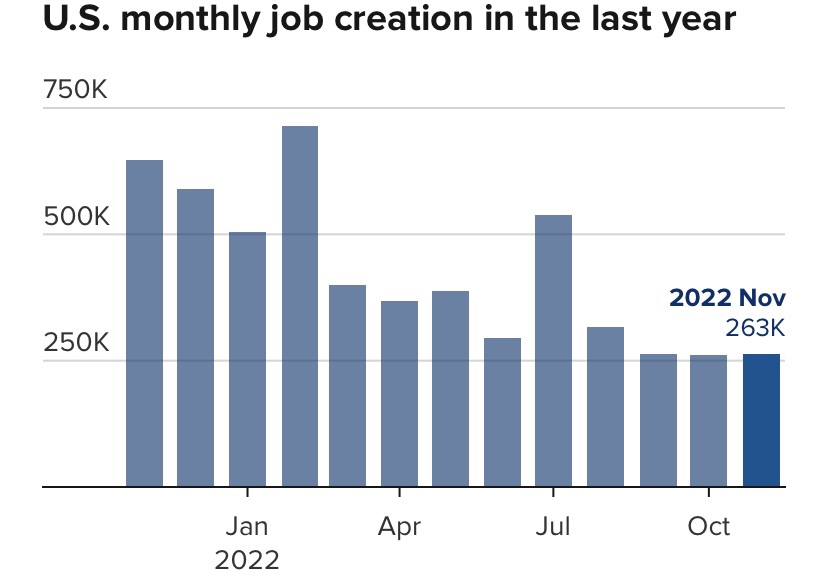

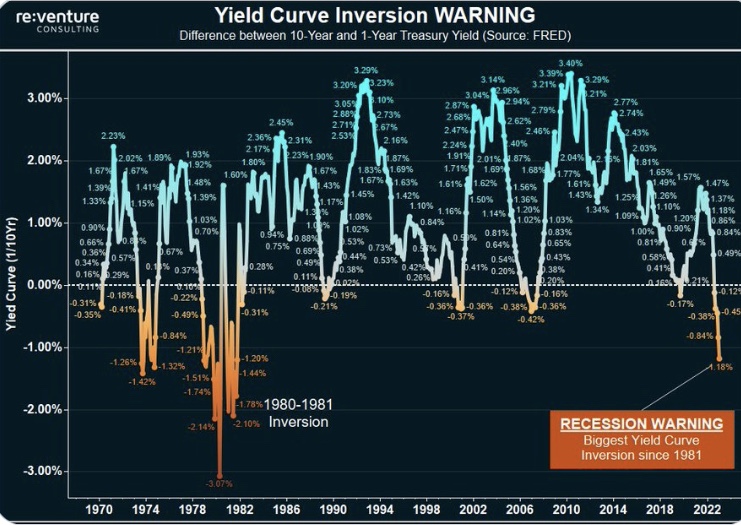

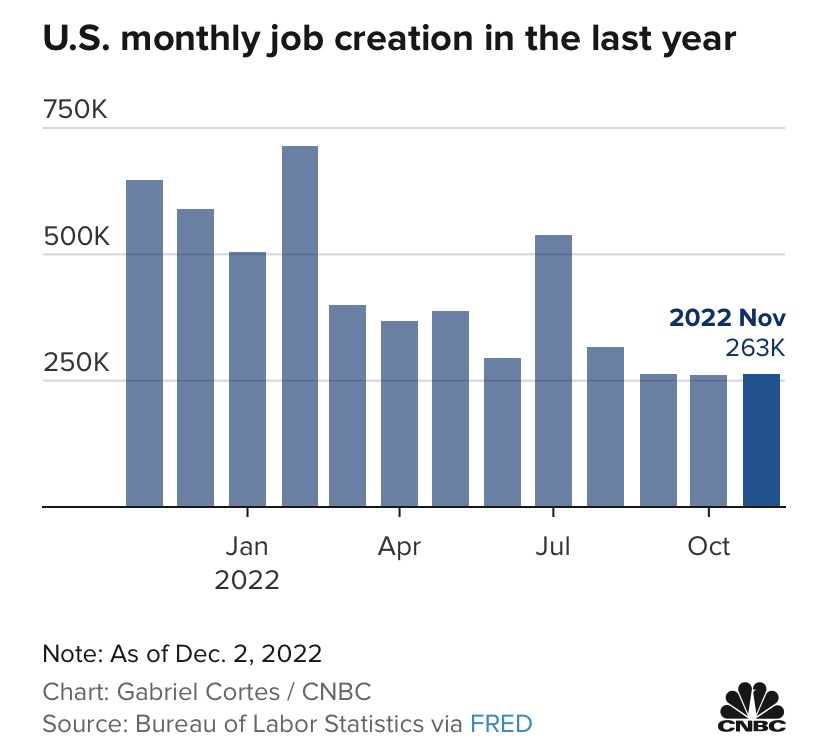

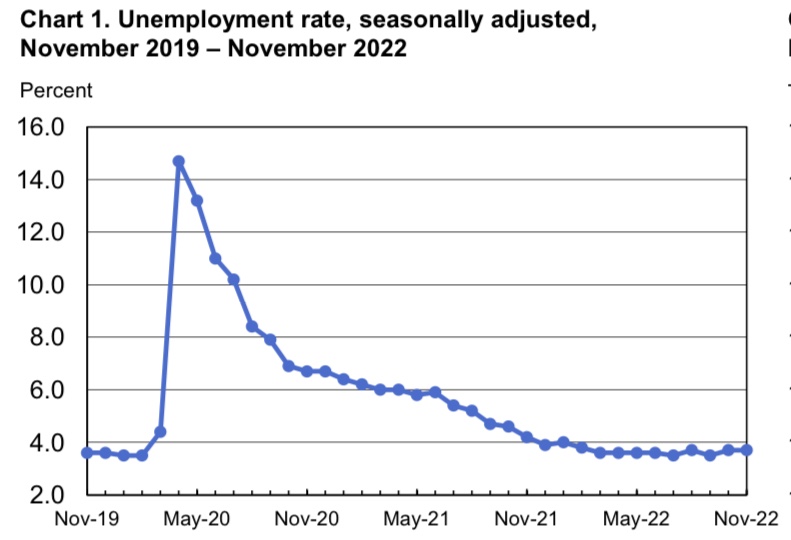

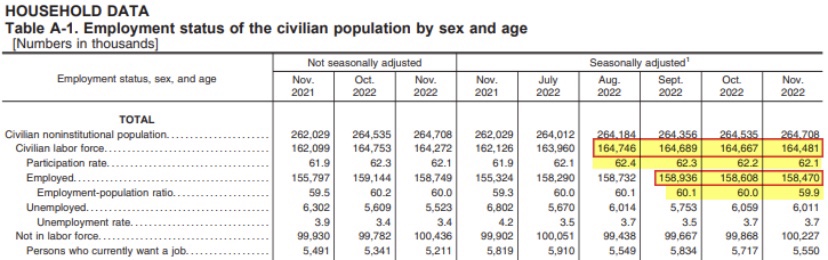

Of course, unlike late Weimar Germany, when Jews were blamed for economic (and other) problems, the Jew hatred we’re witnessing in the U.S. today has little to do with the immediate state of the economy. Conditions now are nothing like what prevailed in Germany as the Great Depression took hold, despite current inflationary stresses on real household incomes.

And yet some hold Jews in contempt for their relative economic success, a fact that is bound up with the frequency with which Jews are placed at the center of economic conspiracy theories. One would think Jews to be the ultimate “white oppressors”. But it seems that much of the current wave of anti-Semitism comes from fairly elite quarters, ensconced within major institutions where its sympathizers are insulated from day-to-day economic pressures.

And that brings us to a frightening aspect of the current malaise: how heavily institutionalized the hatred for certain groups or “classes” has already become. This owes to the blame directed toward whites, men, Jews, and Asians presumed to have been endowed with an inside track on success at the expense of others. Success of any kind, in the narrative of “critical” social justice, is “oppressive”, as if success is a zero-sum game.

Here is Philip Carl Salzman on this point:

“The ‘social justice’ political analysis is founded on the Marxist conviction that society is divided into two classes: oppressors and victims. The corresponding ‘social justice’ ethic is that victims must be raised up and celebrated and that oppressors must be suppressed and eliminated.”

This thinking has been integrated into the policies, practices and rhetoric taught in schools at all levels, corporations and nonprofits, social and traditional media, and government (including intelligence agencies and the military). This level of integration gives diversity, equity, and inclusivity (DEI) policies coercive force on behalf of so-called “protected groups”, in the parlance of anti-discrimination law. When those practices are enforced by government in various ways, the private gains extracted from “unprotected” groups amount to fascism.

Bari Weiss wrote an article in Tablet last week entitled “End DEI” in which she describes her bemused reaction as a student in the early 2000s to nascent DEI rhetoric. (Also see her recent speech to the Federalist Society here.) It’s more obvious today, but even then she recognized the hate inherent in DEI doctrine. She crystallizes the dangers she saw in DEI ideology:

“What I saw was a worldview that replaced basic ideas of good and evil with a new rubric: the powerless (good) and the powerful (bad). It replaced lots of things. Colorblindness with race-obsession. Ideas with identity. Debate with denunciation. Persuasion with public shaming. The rule of law with the fury of the mob.

“People were to be given authority in this new order not in recognition of their gifts, hard work, accomplishments, or contributions to society, but in inverse proportion to the disadvantages their group had suffered, as defined by radical ideologues. According to them, as Jamie Kirchick concisely put it in these pages: ‘Muslim > gay, Black > female, and everybody > the Jews.’”

Weiss says Jewish leaders told her, at that time, not to be hysterical, that these perverse ideas would ultimately pass like any fad. That sounds so eerily familiar. Instead, we’ve witnessed a widespread ideological takeover.

“If underrepresentation is the inevitable outcome of systemic bias, then overrepresentation—and Jews are 2% of the American population—suggests not talent or hard work, but unearned privilege. This conspiratorial conclusion is not that far removed from the hateful portrait of a small group of Jews divvying up the ill-gotten spoils of an exploited world.

“It isn’t only Jews who suffer from the suggestion that merit and excellence are dirty words. It is strivers of every race, ethnicity, and class. That is why Asian American success, for example, is suspicious. The percentages are off. The scores are too high. From whom did you steal all that success?”

The whole DEI enterprise is corrupt and unethical. It denies the meritorious in favor of those having certain superficial characteristics like the “right” skin color. That is evil and economically demented besides. It also breeds hatred that often flows both ways between classes of people, creating an incendiary environment. That we’re talking about systemic, legalized discrimination against any group is disturbing enough, but when small minorities are “othered” in this way, the potential for violent action against them is magnified. But this is just where the DEI mindset leads its proponents and beneficiaries.

Our slide into this monstrous “social justice” regime mirrors the insanity and anger that was fomented against certain “out groups” when the Nazi’s accumulated power in the latter years of the Weimar Republic. Too many today have succumbed to this zero-sum psychology, young and old alike. Fortunately, they are beginning to face some fierce resistance, but those who extol the supposed righteousness of the class struggle via DEI won’t easily give up. Our institutions are infested with their kind.

As long as influential people preach the virtues of DEI and social justice, the danger of a headlong plunge into genocidal madness is possible. And the sad truth is that normal human beings are subject to social manipulation of the most evil kind. David Foster at Ricochet: quotes an address given by C.S. Lewis in which he emphasizes this point. His words are haunting:

“Of all the passions, the passion for the Inner Ring is most skillful in making a man who is not yet a very bad man do very bad things.”

Elsewhere in Lewis’ address, he says:

“And the prophecy I make is this. To nine out of ten of you the choice which could lead to scoundrelism will come, when it does come, in no very dramatic colours. Obviously bad men, obviously threatening or bribing, will almost certainly not appear. Over a drink, or a cup of coffee, disguised as triviality and sandwiched between two jokes, from the lips of a man, or woman, whom you have recently been getting to know rather better and whom you hope to know better still—just at the moment when you are most anxious not to appear crude, or naïf or a prig—the hint will come. It will be the hint of something which the public, the ignorant, romantic public, would never understand: something which even the outsiders in your own profession are apt to make a fuss about: but something, says your new friend, which ‘we’ — and at the word ‘we’ you try not to blush for mere pleasure—something ‘we’ always do.

“And you will be drawn in, if you are drawn in, not by desire for gain or ease, but simply because at that moment, when the cup was so near your lips, you cannot bear to be thrust back again into the cold outer world. It would be so terrible to see the other man’s face—that genial, confidential, delightfully sophisticated face—turn suddenly cold and contemptuous, to know that you had been tried for the Inner Ring and rejected. And then, if you are drawn in, next week it will be something a little further from the rules, and next year something further still, but all in the jolliest, friendliest spirit. It may end in a crash, a scandal, and penal servitude; it may end in millions, a peerage and giving the prizes at your old school. But you will be a scoundrel.”