Tags

Ample Reserves, Budget Deficit, Core CPI, Demand-Side Inflation, Energy Policy, Expected Inflation, Hard Landing, Inflation, Inflation Targeting, Inverted Yield Curve, Jeremy Siegel, John Cochrane, M2, Median CPI, Median PCE, Monetary Base, Monetary policy, PCE Deflator, Price Signals, Recession, Scott Sumner, Soft Landing, Supply-Side Inflation, Trimmed CPI

The debate over the Federal Reserve’s policy stance has undergone an interesting but understandable shift, though I disagree with the “new” sentiment. For the better part of this year, the consensus was that the Fed waited too long and was too dovish about tightening monetary policy, and I agree. Inflation ran at rates far in excess of the Fed’s target, but the necessary correction was delayed and weak at the start. This violated the necessary symmetry of a legitimate inflation-targeting regime under which the Fed claims to operate, and it fostered demand-side pressure on prices while risking embedded expectations of higher prices. The Fed was said to be “behind the curve”.

Punch Bowl Resentment

The past few weeks have seen equity markets tank amid rising interest rates and growing fears of recession. This brought forth a chorus of panicked analysts. Bloomberg has a pretty good take on the shift. Hopes from some economists for a “soft landing” notwithstanding, no one should have imagined that tighter monetary policy would be without risk of an economic downturn. At least the Fed has committed to a more aggressive policy with respect to price stability, which is one of its key mandates. To be clear, however, it would be better if we could always avoid “hard landings”, but the best way to do that is to minimize over-stimulation by following stable policy rules.

Price Trends

Some of the new criticism of the Fed’s tightening is related to a perceived change in inflation signals, and there is obvious logic to that point of view. But have prices really peaked or started to reverse? Economist Jeremy Siegel thinks signs point to lower inflation and believes the Fed is being too aggressive. He cites a series of recent inflation indicators that have been lower in the past month. Certainly a number of commodity prices are generally lower than in the spring, but commodity indices remain well above their year-ago levels and there are new worries about the direction of oil prices, given OPEC’s decision this week to cut production.

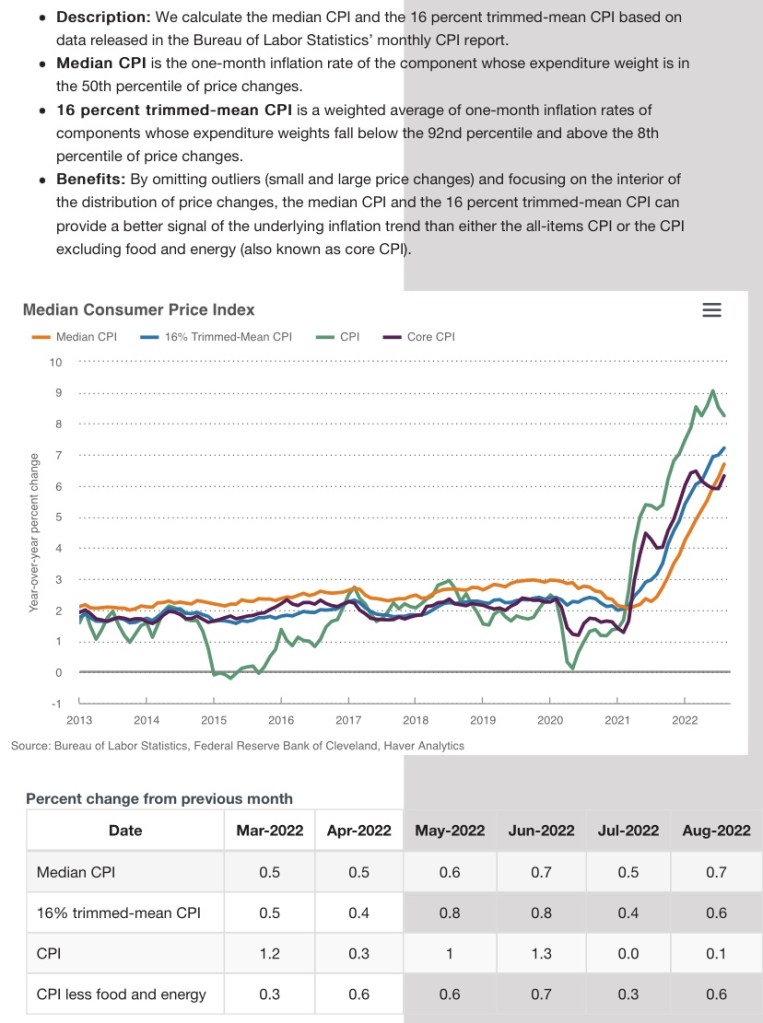

Central trends in consumer prices show that there is a threat of inflation that may be fairly resistant to economic weakness and Fed actions, as the following chart demonstrates:

Overall CPI growth stopped accelerating after June, and it wasn’t just moderation in oil prices that held it back (and that moderation might soon reverse). Growth of the Core CPI, which excludes food and energy prices, stopped accelerating a bit earlier, but growth in the CPI and the Core CPI are still running above 8% and 6%, respectively. More worrisome is the continued upward trend in more central measures of CPI growth. Growth in the median component of the CPI continues to accelerate, as has the so-called “Trimmed CPI”, which excludes the most extreme sets of high and low growth components. The response of those central measures lagged behind the overall CPI, but it means there is still inflationary momentum in the economy. There is a substantial risk that expectations of a more permanent inflation are becoming embedded in expectations, and therefore in price and wage setting, including long-term contracts.

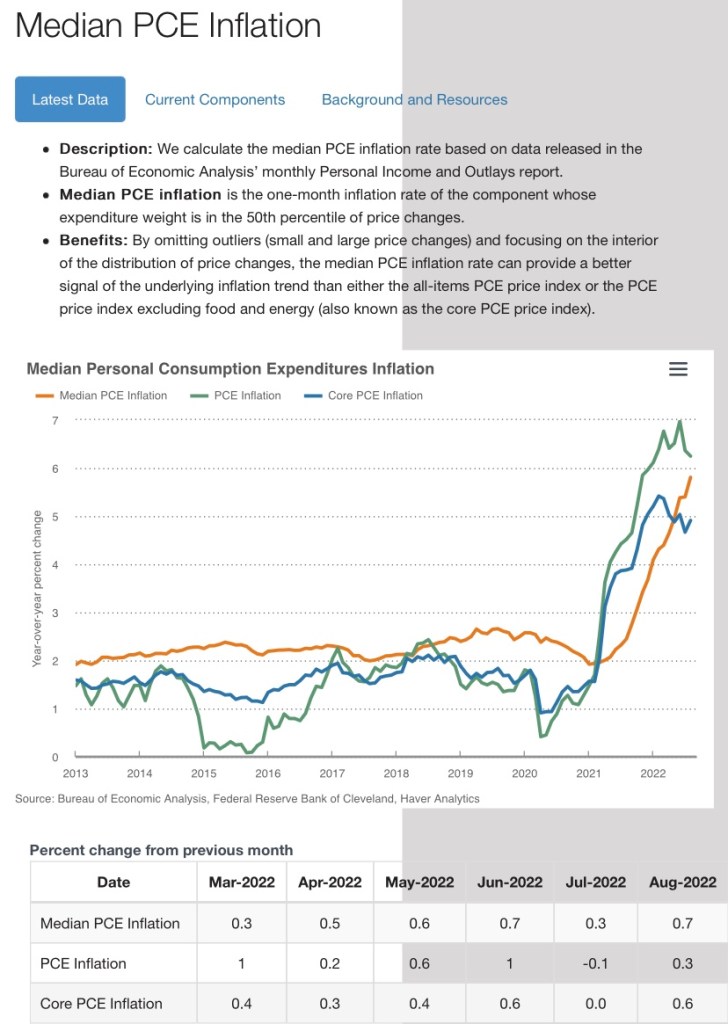

The Fed pays more attention to a measure of prices called the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) deflator. Unlike the CPI, the PCE deflator accounts for changes in the composition of a typical “basket” of goods and services. In particular, the Fed focuses most closely on the Core PCE deflator, which excludes food and energy prices. Inflation in the PCE deflator is lower than the CPI, in large part because consumers actively substitute away from products with larger price increases. However, the recent story is similar for these two indices:

Both overall PCE inflation and Core PCE inflation stopped accelerating a few months ago, but growth in the median PCE component has continued to increase. This central measure of inflation still has upward momentum. Again, this raises the prospect that inflationary forces remain strong, and that higher and more widespread expected inflation might make the trend more difficult for the Fed to rein in.

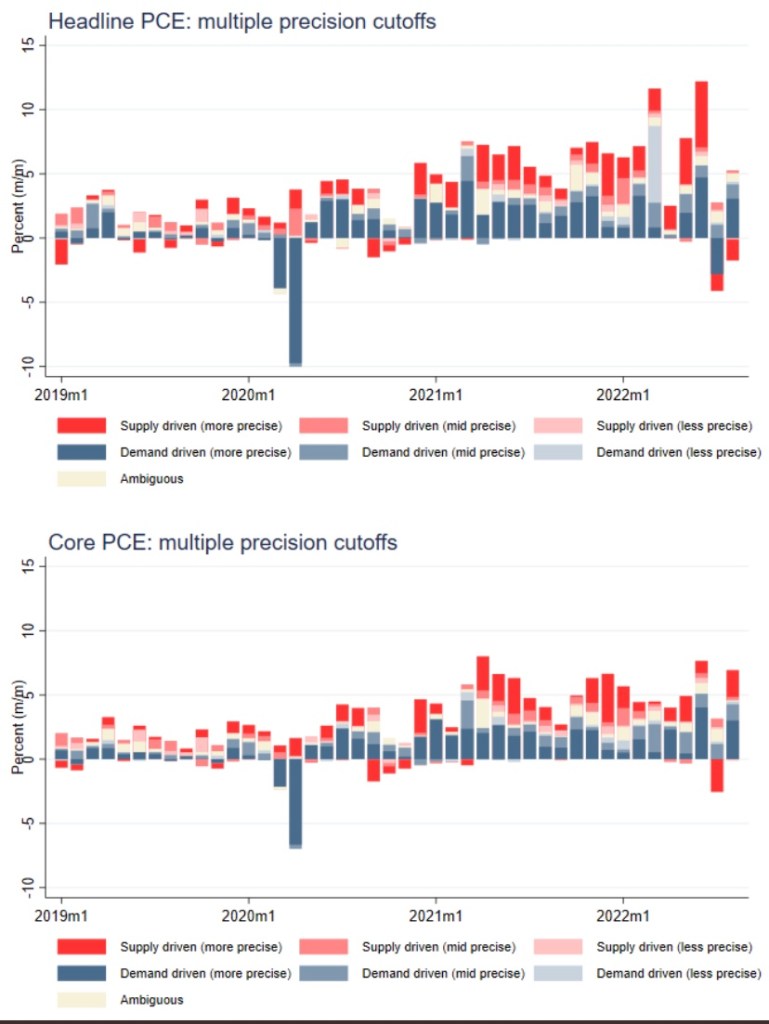

That leaves the Fed little choice if it hopes to bring inflation back down to its target level. It’s really a only a choice of whether to do it faster or slower. One big qualification is that the Fed can’t do much about supply shortfalls, which have been a source of price pressure since the start of the rebound from the pandemic. However, demand pressures have been present since the acceleration in price growth began in earnest in early 2021. At this point, it appears that they are driving the larger part of inflation.

The following chart shows share decompositions for growth in both the “headline” PCE deflator and the Core PCE deflator. Actual inflation rates are NOT shown in these charts. Focus only on the bolder colored bars. (The lighter bars represent estimates having less precision.) Red represents “supply-side” factors contributing to changes in the PCE deflator, while blue summarizes “demand-side” factors. This division is based on a number of assumptions (methodological source at the link), but there is no question that demand has contributed strongly to price pressures. At least that gives a sense about how much of the inflation can be addressed by actions the Fed might take.

I mentioned the role of expectations in laying the groundwork for more permanent inflation. Expected inflation not only becomes embedded in pricing decisions: it also leads to accelerated buying. So expectations of inflation become a self-fulfilling prophesy that manifests on both the supply side and the demand-side. Firms are planning to raise prices in 2023 because input prices are expected to continue rising. In terms of the charts above, however, I suspect this phenomenon is likely to appear in the “ambiguous” category, as it’s not clear that the counting method can discern the impacts of expectations.

What’s a Central Bank To Do?

Has the Fed become too hawkish as inflation accelerated this year while proving to be more persistent than expected? One way to look at that question is to ask whether real interest rates are still conducive to excessive rate-sensitive demand. With PCE inflation running at 6 – 7% and Treasury yields below 4%, real returns are still negative. That’s hardly seems like a prescription for taming inflation, or “hawkish”. Rate increases, however, are not the most reliable guide to the tenor of monetary policy. As both John Cochrane and Scott Sumner point out, interest rate increases are NOT always accompanied by slower money growth or slowing inflation!

However, Cochrane has demonstrated elsewhere that it’s possible the Fed was on the right track with its earlier dovish response, and that price pressures might abate without aggressive action. I’m skeptical to say the least, and continuing fiscal profligacy won’t help in that regard.

The Policy Instrument That Matters

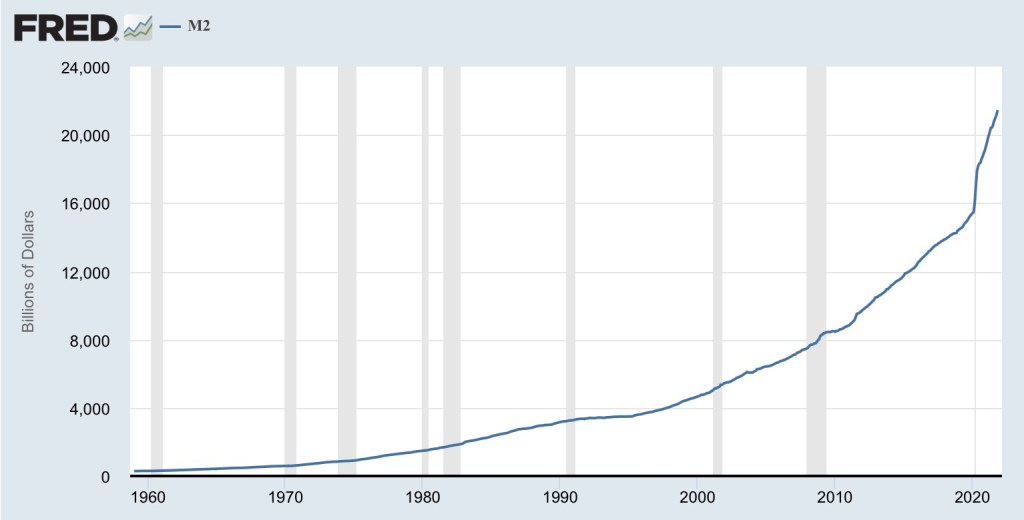

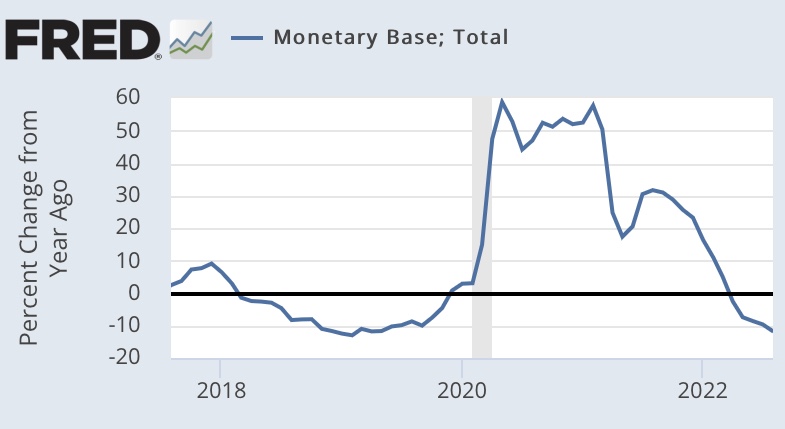

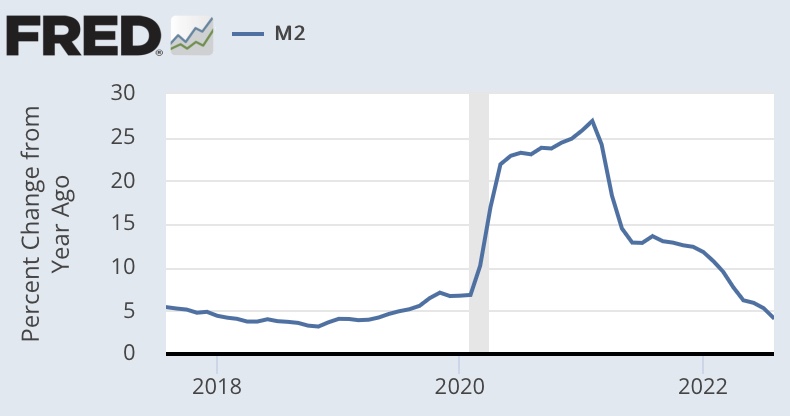

Ultimately, the best indicator that policy has tightened is the dramatic slowdown (and declines) in the growth of the monetary aggregates. The three charts below show five years of year-over-year growth in two monetary measures: the monetary base (bank reserves plus currency in circulation), and M2 (checking, saving, money market accounts plus currency).

Growth of these aggregates slowed sharply in 2021 after the Fed’s aggressive moves to ease liquidity during the first year of the pandemic. The monetary base and M2 growth have slowed much more in 2022 as the realization took hold that inflation was not transitory, as had been hoped. Changes in the growth of the money stock takes time to influence economic activity and inflation, but perhaps the effects have already begun, or probably will in earnest during the first half of 2023.

The Protuberant Balance Sheet

Since June, the Fed has also taken steps to reduce the size of its bloated balance sheet. In other words, it is allowing its large holdings of U.S. Treasuries and Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities to shrink. These securities were acquired during rounds of so-called quantitative easing (QE), which were a major contributor to the money growth in 2020 that left us where we are today. The securities holdings were about $8.5 trillion in May and now stand at roughly $8.2 trillion. Allowing the portfolio to run-off reduces bank reserves and liquidity. The process was accelerated in September, but there is increasing tension among analysts that this quantitative tightening will cause disruptions in financial markets and ultimately the real economy, There is no question that reducing the size of the balance sheet is contractionary, but that is another necessary step toward reducing the rate of inflation.

The Federal Spigot

The federal government is not making the Fed’s job any easier. The energy shortages now afflicting markets are largely the fault of misguided federal policy restricting supplies, with an assist from Russian aggression. Importantly, however, heavy borrowing by the U.S. Treasury continues with no end in sight. This puts even more pressure on financial markets, especially when such ongoing profligacy leaves little question that the debt won’t ever be repaid out of future budget surpluses. The only way the government’s long-term budget constraint can be preserved is if the real value of that debt is bid downward. That’s where the so-called inflation tax comes in, and however implicit, it is indeed a tax on the public.

Don’t Dismiss the Real Costs of Inflation

Inflation is a costly process, especially when it erodes real wages. It takes its greatest toll on the poor. It penalizes holders of nominal assets, like cash, savings accounts, and non-indexed debt. It creates a high degree of uncertainty in interpreting price signals, which ordinarily carry information to which resource flows respond. That means it confounds the efficient allocation of resources, costing all of us in our roles as consumers and producers. The longer it continues, the more it erodes our economy’s ability to enhance well being, not to mention the instability it creates in the political environment.

Imminent Recession?

So far there are only limited signs of a recession. Granted, real GDP declined in both the first and second quarters of this year, but many reject that standard as overly broad for calling a recession. Moreover, consumer spending held up fairly well. Employment statistics have remained solid, though we’ll get an update on those this Friday. Nevertheless, payroll gains have held up and the unemployment rate edged up to a still-low 3.7% in August.

Those are backward-looking signs, however. The financial markets have been signaling recession via the inverted yield curve, which is a pretty reliable guide. The weak stock market has taken a bite out of wealth, which is likely to mean weaker demand for goods. In addition to energy-supply shocks, the strong dollar makes many internationally-traded commodities very costly overseas, which places the global economy at risk. Moreover, consumers have run-down their savings to some extent, corporate earnings estimates have been trimmed, and the housing market has weakened considerably with higher mortgage rates. Another recent sign of weakness was a soft report on manufacturing growth in September.

Deliver the Medicine

The Fed must remain on course. At least it has pretensions of regaining credibility for its inflation targeting regime, and ultimately it must act in a symmetric way when inflation overshoots its target, and it has. It’s not clear how far the Fed will have to go to squeeze demand-side inflation down to a modest level. It should also be noted that as long as supply-side pressures remain, it might be impossible for the Fed to engineer a reduction of inflation to as low as its 2% target. Therefore, it must always bear supply factors in mind to avoid over-contraction.

As to raising the short-term interest rates the Fed controls, we can hope we’re well beyond the halfway point. Reductions in the Fed’s balance sheet will continue in an effort to tighten liquidity and to provide more long-term flexibility in conducting operations, and until bank reserves threaten to fall below the Fed’s so-called “ample reserves” criterion, which is intended to give banks the wherewithal to absorb small shocks. Signs that inflationary pressures are abating is a minimum requirement for laying off the brakes. Clear signs of recession would also lead to more gradual moves or possibly a reversal. But again, demand-side inflation is not likely to ease very much without at least a mild recession.