Tags

Balanced Trade, Capital Flows, Excise Tax, Export Tax, Import Substitution, Lerner Effect, Lerner Symmetry, Perfect Competition, Price Flexibility, Regressive Tax, Scott Sumner, Tariffs, Tax Burden, Trade Retaliation, Trump Administration, Tyler Cowen, Workably Competitive, WTO, Yale Budget Lab

Tariffs have far-reaching effects that strike some as counter-intuitive, but they are real forces nevertheless. Much like any selective excise tax, tariffs reduce the quantity demanded of the taxed good; buyers (importers) pay more, but sellers of the good (foreign exporters) extract less revenue. Suppose those sellers happen to be the primary buyers of what you produce. Because they have less to spend, you also will earn less revenue.

The Lerner Effect

The imposition of tariffs by the U.S. means that foreigners have fewer dollars to spend on exports from the U.S. (as well as fewer dollars to invest in the U.S. assets like Treasury bonds, stocks, and physical capital). That much is true without any change in the exchange rate. However, lower imports also imply a stronger dollar, further eroding the ability of foreigners to purchase U.S. exports.

The implications of the import tariff for U.S. exports may be even more starkly negative. Scott Sumner discusses an economic principle called Lerner Symmetry: a tax on imports can be the exact equivalent of a tax on exports! That’s because two-directional trade flows rely on two-directional flows of income.

Note that this has nothing to do with foreign retaliation against U.S. trade policy, although that will also hurt U.S. exporters. Nor is it a consequence of the very real cost increase that tariffs impose on U.S. export manufacturers who require foreign inputs. That’s a separate issue. Lerner Symmetry is simply part of the mechanics of trade flows in response to a one-sided tariff shock.

Assumptions For Lerner Symmetry

Scott Sumner enumerated certain conditions that must be in place for full Lerner Symmetry. While they might seem strict, the Lerner effect is nevertheless powerful under relaxed assumptions (though somewhat weaker than full Lerner Symmetry).

As Sumner puts it, while full Lerner Symmetry requires perfect competition, nearly all markets are “workably competitive”. In the longer-run, assumptions of price flexibility and full employment are anything but outlandish. Complete non-retaliation is an unrealistic assumption, given the breadth and scale of the Trump tariffs. Some countries will retaliate, but not all, and it is certainly not in their best interests to do so. The assumption of balanced trade is one and the same as the assumption of no capital flows; a departure from these “two” assumptions weakens the symmetry between tariffs and export taxes because a reduction in capital flows takes up some of the slack from lower revenue earned by foreign producers.

Trump Tariff Impacts

So here we are, after large hikes in tariffs and perhaps more on the way. Or perhaps more exceptions will be carved out for favored supplicants in return for concessions of one kind or another. All that is economically and ethically foul.

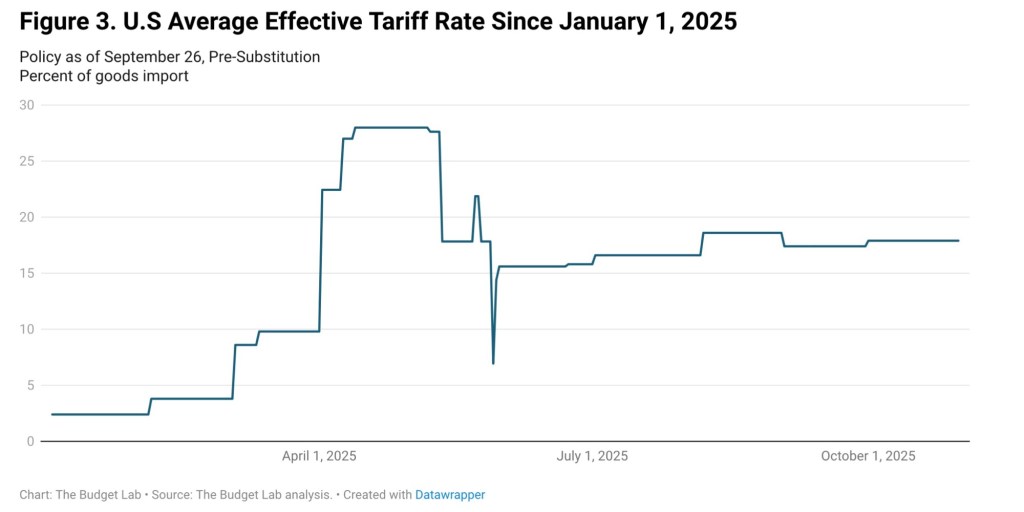

But how are imports and exports faring? Here I’ll quote the Yale Budget Lab’s (YBL) September 26th report on tariffs, which includes the chart shown at the top of this post:

“Consumers face an overall average effective tariff rate of 17.9%, the highest since 1934. After consumption shifts, the average tariff rate will be 16.7%, the highest since 1936. …

The post-substitution price increase settles at 1.4%, a $1,900 loss per household.“

The “post-substitution” modifier refers to the fact that price increases caused by tariffs would be somewhat larger but for consumers’ attempts to find lower-priced domestic substitutes. Suppose the PCE deflator ends 2025 with a 2.8% annual increase. The YBL’s price estimate implies that absent the Trump tariffs, the PCE would have increased 1.4%. If that seems small to you (and the tariff effect seems large to you), recall that monetary policy has been and remains moderately restrictive, so we might have expected some tapering in the PCE without tariffs.

We also know that the early effects of the tariffs have been dominated by thinner margins earned by businesses on imported goods. Those firms have been swallowing a large portion of the tariff burden, but they will increasingly attempt to pass the added costs into prices.

But back to the main topic … what about exports? Unfortunately, the data is subject to lags and revisions, so it’s too early to say much. However, we know exports won’t decline as much as imports, given the lack of complete Lerner symmetry. YBL predicts a drop in exports of 14%, but that includes retaliatory effects. In August the WTO predicted only about a 4% decline, which would be about half the decline in imports.

Seeking Compensatory Rents

More telling perhaps, and it may or may not be a better indicator of the Lerner effect, is the clamoring for relief by American farmers who face diminished export opportunities. As Tyler Cowen says, “Lerner Symmetry Bites”. Other industries will feel the pinch, but many are likely preoccupied with the more immediate problem of increases in the direct cost of imported materials and components.

The farm lobby is certainly on its toes. The Trump Administration is now asking U.S. taxpayers to subsidize soybean producers to the tune of $15 billion. Those exporting farmers are undoubtedly victimized by tariffs. But so much for deficit reduction! More from Cowen:

“Using tariff revenue to subsidize the losses of exporters is a textbook illustration of Lerner Symmetry because the export losses flow directly from the tax on imports! The irony is that President Trump parades the subsidies as a victory while in fact they are simply damage control for a policy he created.“

A List of Harms

Tariffs are as distortionary as any other selective excise tax. They restrict choice and penalize domestic consumers and businesses, whose judgement of cost and quality happen to favor goods from abroad. Tariffs create cost and price pressures in some industries that both erode profit margins and reduce real incomes. For consumers, a tariff is a regressive tax, harming the poor disproportionately.

Tariffs also diminish foreign flows of capital to the U.S., slowing the long-term growth of the economy as well as productivity growth and real wages. And the Lerner effect implies that tariffs harm U.S. exporters by reducing the dollars available to foreigners for purchasing goods from the U.S. In these several ways, Americans are made worse off by tariffs.

We now see attempts to cover for the damage done by tariffs by subsidizing the victims. A “tariff dividend” to consumers? Subsidies to exporters harmed by the Lerner effect? In both cases, we would forego the opportunity to pay down the bloated public debt. Thus, the American taxpayer will be penalized as well.