Tags

Affordable Care Act, Block Grants, DOGE, Federal Matching Funds, Federal Medical Assistance Percentages, FMAP, Government Accountability Office, Issues & Insights, Joe Biden, Medicaid, National Library of Medicine, Obamacare, Provider Reimbursements, Provider Taxes, Supplemental Reimbursements

It’s been underway in various forms for a long time, at least since the early 1980s. It’s a basic variant of what the National Library of Medicine once called “creative financing” by some states “to get more federal dollars than they otherwise would qualify for” under Medicaid. It was even recognized as a scam by Joe Biden during Barack Obama’s presidency, and more recently by a number of legislators. Perhaps DOGE can do something to bring it under scrutiny, but ending it would probably take legislation.

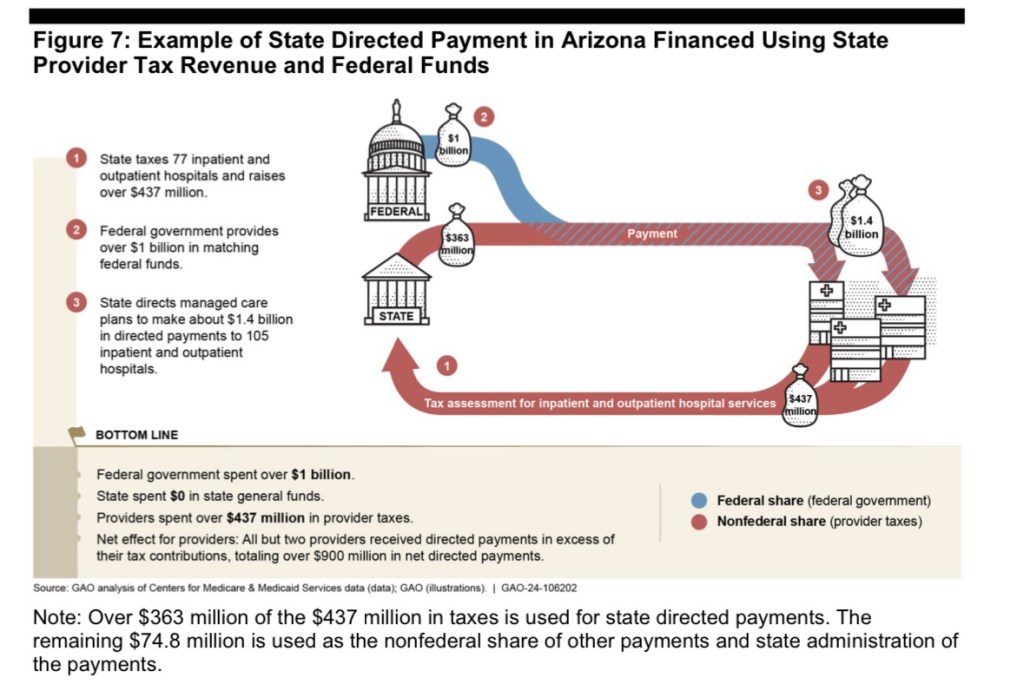

Here’s the gist of it: increases in state Medicaid reimbursements qualify for a federal match at a rate known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAPs). First, increases in Medicaid reimbursements must be funded at the state level. To do this, states tax Medicaid providers, but then the revenue is kicked back to providers in higher reimbursements. The deluge of matching federal dollars follows, and states are free to use those dollars in their general budgets.

FMAPs vary based on state income level, so states with poorer residents have higher matching rates. The minimum FMAP is 50%, and it ranges up to 90% for marginal reimbursements falling under expanded Medicaid under Obamacare. The dollar value of the federal match is not capped.

The graphic at the top of this post highlights the circularity of this funding scheme. The graphic is taken from the Government Accountability Office’s “Medicaid Managed Care: Rapid Spending Growth In State Directed Payments Needs Enhanced Oversight and Transparency”. Here’s how Issues & Insights puts it:

“Let’s say, for example, a state imposes a provider tax on hospitals that raises $100 million. And then it returns that $100 million to the hospitals in the form of higher Medicaid reimbursement rates. There’s been no increase in benefits. Providers aren’t better off. But the state gets an extra $50 million from the federal government’s matching fund, money that it can use for anything it wants.“

However, whatever the increment to state coffers, and no matter what state programs are funded as a result, the increment is always expressed as a federal contribution to state Medicaid spending. That bit of shading helps cover for the convoluted and pernicious nature of the scheme. The lack of transparency is obvious, cloaking the circular nature of the flow of funds from providers to states and then back to providers. It’s possible that the arrangement inflates total annual Medicaid costs by as $50 – $65 billion a year, or by 6% – 8%.

Of course, this is also a blatant example of bureaucratic waste, and the allocation of “supplemental reimbursements” are a potential seedbed for cronyism and graft.

It would be better for the federal government to simply give states the money under block grants without the rigmarole. But of course that would change the character of the rent seeking already taking place, and the political daylight might not serve beneficiary states and providers well.

Putting aside the deception inherent in the funding mechanism, states vary tremendously in their reliance on federal matching revenue. States with large populations and high average incomes rely more heavily on the circular inflating of Medicaid reimbursements. California and New York lead the way in both Medicaid provider taxes and federal matching funds. Alaska, however, imposes no Medicaid provider taxes, and smaller states like Wyoming collect little in provider taxes.

High income states receive lower FMAPs, which seemingly encourages both higher Medicaid provider taxes and more “generous” provider reimbursements in order to harvest more federal matching funds. In addition, states have an incentive to participate in expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act in order to receive higher matching rates.

The reciprocal nature of state-level Medicaid provider taxes and provider reimbursements implies a substantial but fictitious component of state Medicaid costs. The purpose is to qualify for federal matching dollars under Medicaid. The governments of 49 states have carried on with this escapade for years. Their misguided defenders insist that the federal contribution is necessary to protect benefits that states might otherwise have to cut. But even that stipulation would not justify the pairing of taxes on and reimbursements to Medicaid providers, which inflates the spending base upon which federal reimbursements are calculated. You have to wonder whether federal taxpayers should forgive the overstatement of costs and misallocation of funds.