Tags

budget deficits, Credible Committments, crowding out, David Beckworth, David Henderson, Discretionary Spending, economic stimulus, Federal Reserve, Great Depression, Housing Bubble, Inflation Reduction Act, Long and Variable Lags, Lucas Critique, Mortgage Crisis, Pandemic Relief, Rational Expectations, Robert Lucas, Shovel-Ready Projects, Spending Multipliers, Stabilization policy, Tyler Cowen

Policy activists have long maintained that manipulating government policy can stabilize the economy. In other words, big spending initiatives, tax cuts, and money growth can lift the economy out of recessions, or budget cuts and monetary contraction can prevent overheating and inflation. However, this activist mirage burned away under the light of experience. It’s not that fiscal and monetary policy are powerless. It’s a matter of practical limitations that often cause these tools to be either impotent or destabilizing to the economy, rather than smoothing fluctuations in the business cycle.

The macroeconomics classes seem like yesterday: Keynesian professors lauded the promise of wise government stabilization efforts: policymakers could, at least in principle, counter economic shocks, particularly on the demand side. That optimistic narrative didn’t end after my grad school days. I endured many client meetings sponsored by macro forecasters touting the fine-tuning of fiscal and monetary policy actions. Some of those economists were working with (and collecting revenue from) government policymakers, who are always eager to validate their pretensions as planners (and saviors). However, seldom if ever do forecasters conduct ex post reviews of their model-spun policy scenarios. In fairness, that might be hard to do because all sorts of things change from initial conditions, but it definitely would not be in their interests to emphasize the record.

In this post I attempt to explain why you should be skeptical of government stabilization efforts. It’s sort of a lengthy post, so I’ve listed section headings below in case readers wish to scroll to points of most interest. Pick and choose, if necessary, though some context might get lost in the process.

- Expectations Change the World

- Fiscal Extravagance

- Multipliers In the Real World

- Delays

- Crowding Out

- Other Peoples’ Money

- Tax Policy

- Monetary Policy

- Boom and Bust

- Inflation Targeting

- Via Rate Targeting

- Policy Coordination

- Who Calls the Tune?

- Stable Policy, Stable Economy

Expectations Change the World

There were always some realists in the economics community. In May we saw the passing of one such individual: Robert Lucas was a giant intellect within the economics community, and one from whom I had the pleasure of taking a class as a graduate student. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Science in 1995 for his applications of rational expectations theory and completely transforming macro research. As Tyler Cowen notes, Keynesians were often hostile to Lucas’ ideas. I remember a smug classmate, in class, telling the esteemed Lucas that an important assumption was “fatuous”. Lucas fired back, “You bastard!”, but proceeded to explain the underlying logic. Cowen uses the word “charming” to describe the way Lucas disarmed his critics, but he could react strongly to rude ignorance.

Lucas gained professional fame in the 1970s for identifying a significant vulnerability of activist macro policy. David Henderson explains the famous “Lucas Critique” in the Wall Street Journal:

“… because these models were from periods when people had one set of expectations, the models would be useless for later periods when expectations had changed. While this might sound disheartening for policy makers, there was a silver lining. It meant, as Lucas’s colleague Thomas Sargent pointed out, that if a government could credibly commit to cutting inflation, it could do so without a large increase in unemployment. Why? Because people would quickly adjust their expectations to match the promised lower inflation rate. To be sure, the key is government credibility, often in short supply.”

Non-credibility is a major pitfall of activist macro stabilization policies that renders them unreliable and frequently counterproductive. And there are a number of elements that go toward establishing non-credibility. We’ll distinguish here between fiscal and monetary policy, focusing on the fiscal side in the next several sections.

Fiscal Extravagance

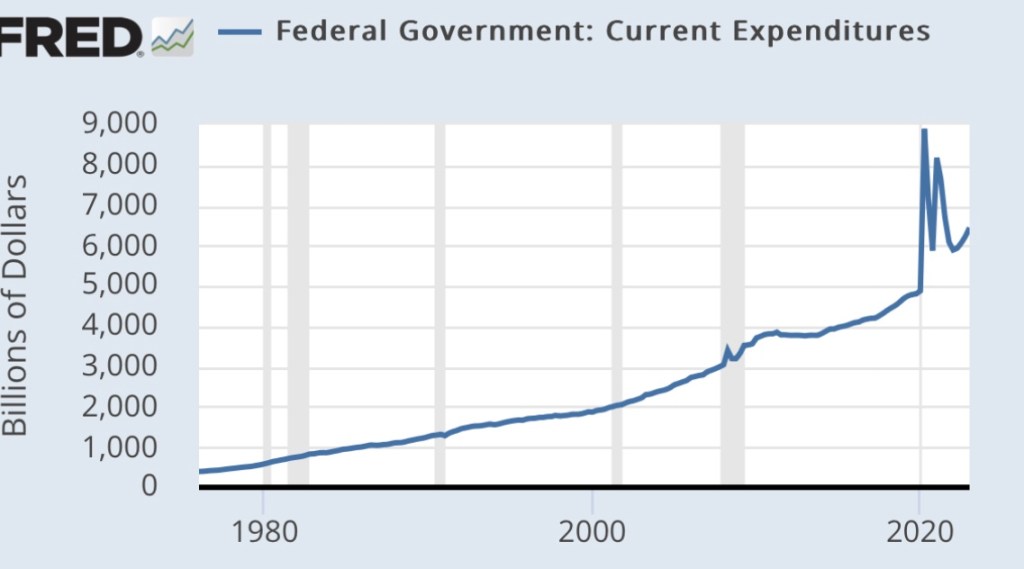

We’ve seen federal spending and budget deficits balloon in recent years. Chronic and growing budget deficits make it difficult to deliver meaningful stimulus, both practically and politically.

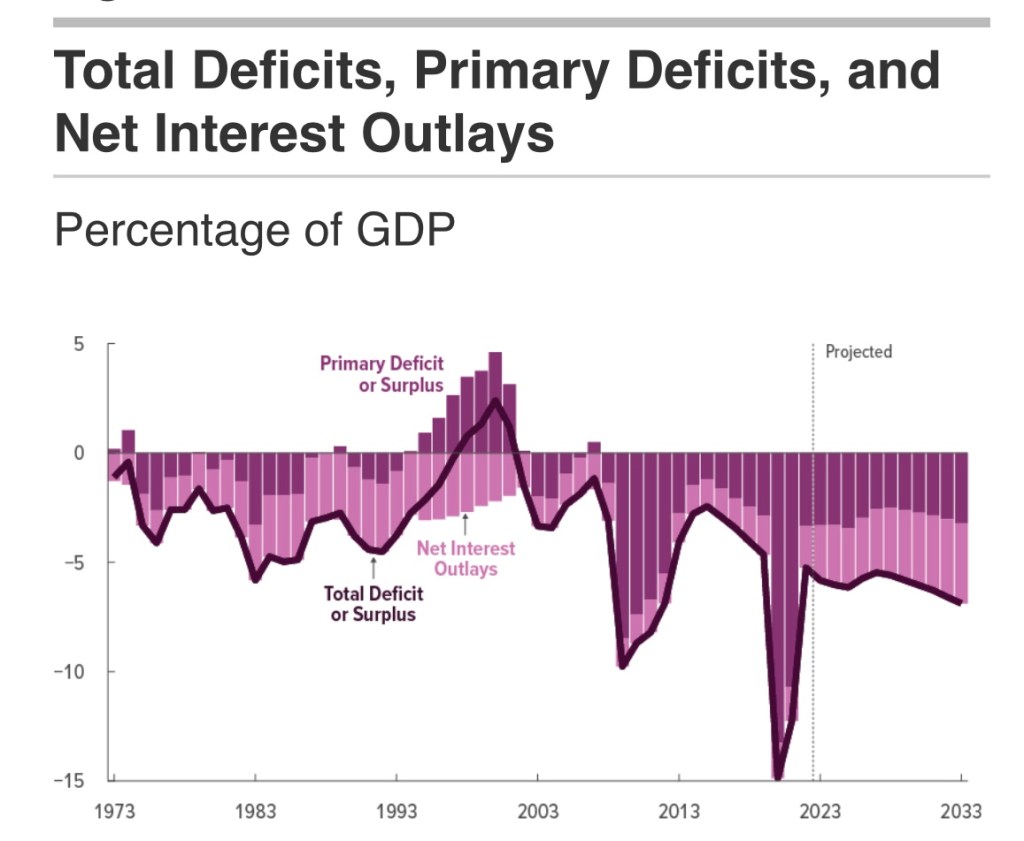

The next chart is from the most recent Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report. It shows the growing contribution of interest payments to deficit spending. Ever-larger deficits mean ever-larger amounts of debt on which interest is owed, putting an ever-greater squeeze on government finances going forward. This is particularly onerous when interest rates rise, as they have over the past few years. Both new debt is issued and existing debt is rolled over at higher cost.

Relief payments made a large contribution to the deficits during the pandemic, but more recent legislation (like the deceitfully-named Inflation Reduction Act) piled-on billions of new subsidies for private investments of questionable value, not to mention outright handouts. These expenditures had nothing to do with economic stabilization and no prayer of reducing inflation. Pissing away money and resources only hastens the debt and interest-cost squeeze that is ultimately unsustainable without massive inflation.

Hardly anyone with future political ambitions wants to address the growing entitlements deficit … but it will catch up with them. Social Security and Medicare are projected to exhaust their respective trust funds in the early- to mid-2030s, which will lead to mandatory benefit cuts in the absence of reform.

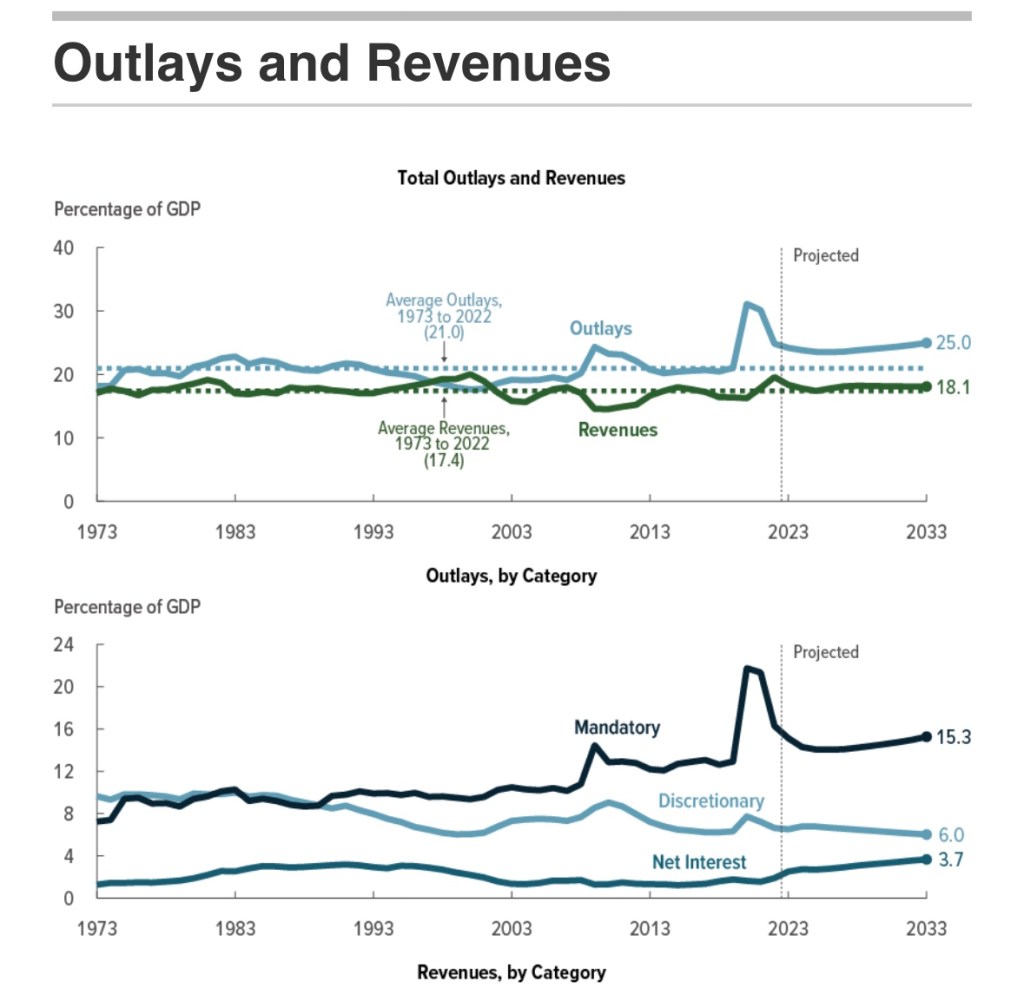

If it still isn’t obvious, the real problem driving the budget imbalance is spending, not revenue, as the next CBO chart demonstrates. The “emergency” pandemic measures helped precipitate our current stabilization dilemma. David Beckworth tweets that the relief measures “spurred a rapid recovery”, though I’d hasten to add that a wave of private and public rejection of extreme precautions in some regions helped as well. And after all, the pandemic downturn was exaggerated by misdirected policies including closures and lockdowns that constrained both the demand and supply sides. Beckworth acknowledges the relief measures “propelled inflation”, but the pandemic also seemed to leave us on a permanently higher spending path. Again, see the first chart below.

The second chart below shows that non-discretionary spending (largely entitlements) and interest outlays are how we got on that path. The only avenue for countercyclical spending is discretionary expenditures, which constitute an ever-smaller share of the overall budget.

We’ve had chronic deficits for years, but we’ve shifted to a much larger and continuing imbalance. With more deficits come higher interest costs, especially when interest rates follow a typical upward cyclical pattern. This creates a potentially explosive situation that is best avoided via fiscal restraint.

Putting other doubts about fiscal efficacy aside, it’s all but impossible to stimulate real economic activity when you’ve already tapped yourself out and overshot in the midst of a post-pandemic economic expansion.

Multipliers In the Real World

So-called spending multipliers are deeply beloved by Keynesians and pork-barrel spenders. These multipliers tell us that every dollar of extra spending ultimately raises income by some multiple of that dollar. This assumes that a portion of every dollar spent by government is re-spent by the recipient, and a portion of that is re-spent again by another recipient. But spending multipliers are never what they’re cracked up to be for a variety of reasons. (I covered these in “Multipliers Are For Politicians”, and also see this post.) There are leakages out of the re-spending process (income taxes, saving, imports), which trim the ultimate impact of new spending on income. When supply constraints bind on economic activity, fiscal stimulus will be of limited power in real terms.

If stimulus is truly expected to be counter-cyclical and transitory, as is generally claimed, then much of each dollar of extra government spending will be saved rather than spent. This is the lesson of the permanent income hypothesis. It means greater leakages from the re-spending stream and a lower multiplier. We saw this with the bulge in personal savings in the aftermath of pandemic relief payments.

Another side of this coin, however, is that cutting checks might be the government’s single-most efficient activity in execution, but it can create massive incentive problems. Some recipients are happy to forego labor market participation as long as the government keeps sending them checks, but at least they spend some of the income.

Delays

Another unappreciated and destabilizing downside of fiscal stimulus is that it often comes too late, just when the economy doesn’t need stimulus. That’s because a variety of delays are inherent in many spending initiatives: legislative, regulatory, legal challenges, planning and design, distribution to various spending authorities, and final disbursement. As I noted here:

“Even government infrastructure projects, heralded as great enhancers of American productivity, are often subject to lengthy delays and cost overruns due to regulatory and environmental rules. Is there any such thing as a federal ‘shovel-ready’ infrastructure project?”

Crowding Out

The supply of savings is limited, but when government borrows to fund deficits, it directly competes with private industry for those savings. Thus, funds that might otherwise pay for new plant, equipment, and even R&D are diverted to uses that should qualify as government consumption rather than long-term investment. Government competition for funds “crowds-out” private activity and impedes growth in the economy’s productive capacity. Thus, the effort to stimulate economic activity is self-defeating in some respects.

Other Peoples’ Money

Government doesn’t respond to price signals the way self-interested private actors do. This indifference leads to mis-allocated resources and waste. It extends to the creation of opportunities for graft and corruption, typically involving diversion of resources into uses that are of questionable productivity (corn ethanol, solar and wind subsidies).

Consider one other type of policy action perceived as counter-cyclical: federal bailouts of failing financial institutions or other troubled businesses. These rescues prop up unproductive enterprises rather than allowing waste to be flushed from the system, which should be viewed as a beneficial aspect of recession. The upshot is that too many efforts at economic stabilization are misdirected, wasteful, ill-timed, and pro-cyclical in impact.

Tax Policy

Like stabilization efforts on the spending side, tax changes may be badly timed. Tax legislation is often complex and can take time for consumers and businesses to adjust. In terms of traditional multiplier analysis, the initial impact of a tax change on spending is smaller than for expenditures, so tax multipliers are smaller. And to the extent that a tax change is perceived as temporary, it is made less effective. Thus, while changes in tax policy can have powerful real effects, they suffer from some of the same practical shortcomings for stabilization as changes in spending.

However, stimulative tax cuts, if well crafted, can boost disposable incomes and improve investment and work incentives. As temporary measures, that might mean an acceleration of certain kinds of activity. Tax increases reduce disposable incomes and may blunt incentives, or prompt delays in planned activities. Thus, tax policy may bear on the demand side as well as the timing of shifts in the economy’s productive potential or supply side.

Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is subject to problems of its own. Again, I refer to practical issues that are seemingly impossible for policy activists to overcome. Monetary policy is conducted by the nation’s central bank, the Federal Reserve (aka, the Fed). It is theoretically independent of the federal government, but the Fed operates under a dual mandate established by Congress to maintain price stability and full employment. Therein lies a basic problem: trying to achieve two goals that are often in conflict with a single policy tool.

Make no mistake: variations in money supply growth can have powerful effects. Nevertheless, they are difficult to calibrate due to “long and variable lags” as well as changes in money “velocity” (or turnover) often prompted by interest rate movements. Excessively loose money can lead to economic excesses and an overshooting of capacity constraints, malinvestment, and inflation. Swinging to a tight policy stance in order to correct excesses often leads to “hard landings”, or recession.

Boom and Bust

The Fed fumbled its way into engineering the Great Depression via excessively tight monetary policy. “Stop and go” policies in the 1970s led to recurring economic instability. Loose policy contributed to the housing bubble in the 2000s, and subsequent maladjustments led to a mortgage crisis (also see here). Don’t look now, but the inflationary consequences of the Fed’s profligacy during the pandemic prompted it to raise short-term interest rates in the spring of 2022. It then acted with unprecedented speed in raising rates over the past year. While raising rates is not always synonymous with tightening monetary conditions, money growth has slowed sharply. These changes might well lead to recession. Thus, the Fed seems given to a pathology of policy shifts that lead to unintentional booms and busts.

Inflation Targeting

The Fed claims to follow a so-called flexible inflation targeting policy. In reality, it has reacted asymmetrically to departures from its inflation targets. It took way too long for the Fed to react to the post-pandemic surge in inflation, dithering for months over whether the surge was “transitory”. It wasn’t, but the Fed was reluctant to raise its target rates in response to supply disruptions. At the same time, the Fed’s own policy actions contributed massively to demand-side price pressures. Also neglected is the reality that higher inflation expectations propel inflation on the demand side, even when it originates on the supply side.

Via Rate Targeting

At a more nuts and bolts level, today the Fed’s operating approach is to control money growth by setting target levels for several key short-term interest rates (eschewing a more direct approach to the problem). This relies on price controls (short-term interest rates being the price of liquidity) rather than allowing market participants to determine the rates at which available liquidity is allocated. Thus, in the short run, the Fed puts itself into the position of supplying whatever liquidity is demanded at the rates it targets. The Fed makes periodic adjustments to these rate targets in an effort to loosen or tighten money, but it can be misdirected in a world of high debt ratios in which rates themselves drive the growth of government borrowing. For example, if higher rates are intended to reduce money growth and inflation, but also force greater debt issuance by the Treasury, the approach might backfire.

Policy Coordination

While nominally independent, the Fed knows that a particular monetary policy stance is more likely to achieve its objectives if fiscal policy is not working at cross purposes. For example, tight monetary policy is more likely to succeed in slowing inflation if the federal government avoids adding to budget deficits. Bond investors know that explosive increases in federal debt are unlikely to be repaid out of future surpluses, so some other mechanism must come into play to achieve real long-term balance in the valuation of debt with debt payments. Only inflation can bring the real value of outstanding Treasury debt into line. Continuing to pile on new debt simply makes the Fed’s mandate for price stability harder to achieve.

Who Calls the Tune?

The Fed has often succumbed to pressure to monetize federal deficits in order to keep interest rates from rising. This obviously undermines perceptions of Fed independence. A willingness to purchase large amounts of Treasury bills and bonds from the public while fiscal deficits run rampant gives every appearance that the Fed simply serves as the Treasury’s printing press, monetizing government deficits. A central bank that is a slave to the spending proclivities of politicians cannot make credible inflation commitments, and cannot effectively conduct counter-cyclical policy.

Stable Policy, Stable Economy

Activist policies for economic stabilization are often perversely destabilizing for a variety of reasons. Good timing requires good forecasts, but economic forecasting is notoriously difficult. The magnitude and timing of fiscal initiatives are usually wrong, and this is compounded by wasteful planning, allocative dysfunction, and a general absence of restraint among political leaders as well as the federal bureaucracy..

Predicting the effects of monetary policy is equally difficult and, more often than not, leads to episodes of over- and under-adjustment. In addition, the wrong targets, the wrong operating approach, and occasional displays of subservience to fiscal pressure undermine successful stabilization. All of these issues lead to doubts about the credibility of policy commitments. Stated intentions are looked upon with doubt, increasing uncertainty and setting in motion behaviors that lead to undesirable economic consequences.

The best policies are those that can be relied upon by private actors, both as a matter of fulfilling expectations and avoiding destabilization. Federal budget policy should promote stability, but that’s not achievable institutions unable to constrain growth in spending and deficits. Budget balance would promote stability and should be the norm over business cycles, or perhaps over periods as long as typical 10-year budget horizons. Stimulus and restraint on the fiscal side should be limited to the effects of so-called automatic stabilizers, such as tax rates and unemployment compensation. On the monetary side, the Fed would do more to stabilize the economy by adopting formal rules, whether a constant rate of money growth or symmetric targeting of nominal GDP.