Tags

AI-Augmented Capital, Artificial Intelligence, Brian Albrecht, ChatGPT, Comparative advantage, Corner Solution, Deployment Risks, Dwarkesh Patel, Elasticity of Substitution, Erik Schiskin, Factor Intensity, Grok, Labor Demand, Marginal Product, Opportunity cost, Perfect Complements, Perfect Substitutes, Philip Trammell, Reciprocal Advantages, Ronald W. Jones, Scarcity, Substitutability, Technology Shocks

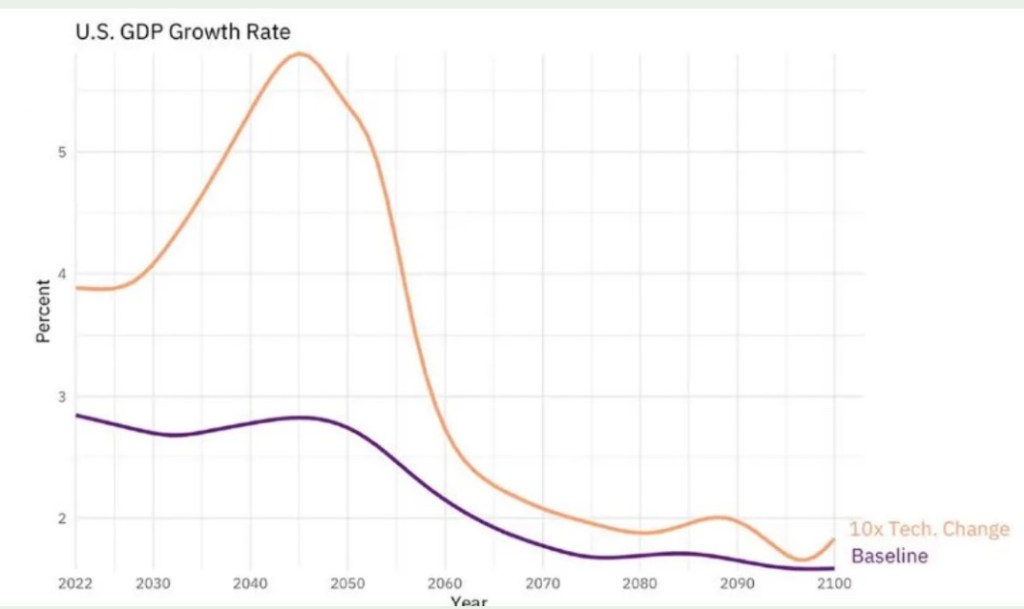

I’m an AI enthusiast, and while I have econometric experience and some knowledge of machine learning techniques, I’m really just a user — I really lack deep technical expertise in the area of AI. However, I use it frequently for research related to my hobbies and to navigate the kinds of practical issues we all encounter day-to-day. With one good question, AI can transform what used to require a series of groping web searches into a much more efficient process and informative result. In small ways like this and in much greater ways, AI will bring dramatically improved levels of productivity and prosperity to the human race.

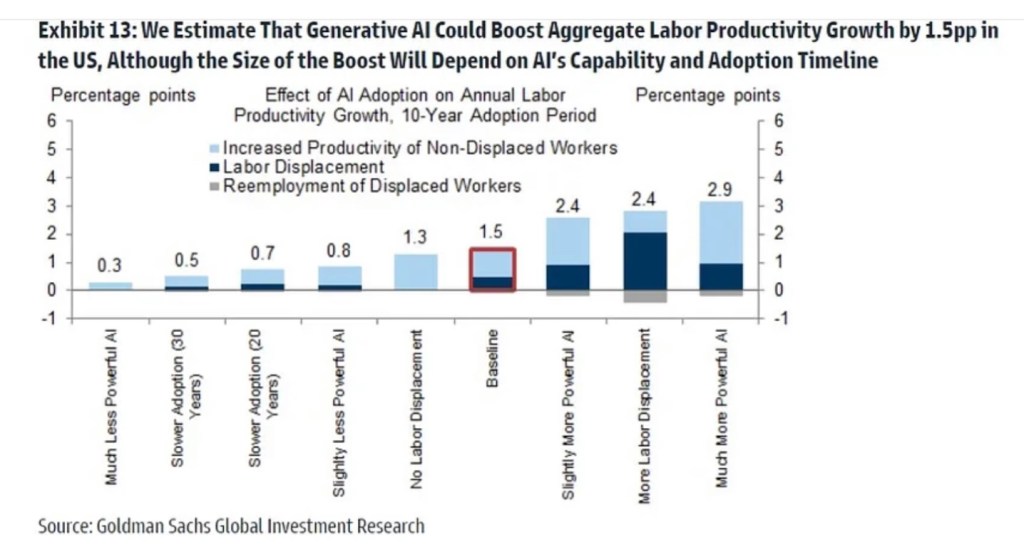

Still, the fear that AI will be catastrophic for human workers is widely accepted. Some claim it’s already happening in the workplace, but the evidence is thin (and see here and here). While it’s certain that some workers will be displaced from their jobs by AI, ultimately new opportunities (and some old ones) will be available.

I’ve written several posts (here, here, here, and here) in which I asserted that a pair of phenomena would ensure continuing employment opportunities for humans in the presence of AI: an ongoing scarcity of resources relative to human wants, and the principle of comparative advantage. Unfortunately, the case I’ve made for the latter was flawed in one critical way: reciprocal comparative advantages across different factors of production are not guaranteed. In trade relationships, trading partners have reciprocal cost advantages with respect to the goods they exchange, and I extended the same principle to factors of production in different sectors. Unfortunately, that analogy with trade does not always hold up, in part because the owners of productive inputs don’t fully engage in direct trade with one another.

Thus, so-called reciprocity of opportunity costs cannot guarantee future employment for humans in a world with AI-augmented capital. Nevertheless, there is a strong case that reciprocity of comparative advantages will exist, whether labor and capital are (less than perfect) complements or substitutes. This is likely to hold up even though human labor and AI-augmented capital could well become more substitutable in the future.

Below, I’ll start by reviewing the principles of scarcity, opportunity costs, and input selection. Then I’ll turn to a couple of other rationales for a more sanguine outlook for human jobs in a world with widely dispersed AI in production. Finally, I’ll provide more detail on whether reciprocal input opportunity costs are likely to exist in a world with AI-augmented capital, and the implications for continued human employment.

Scarcity and Advantages

Scarcity must exist for a resource to carry a positive price. That price is itself a measure of the resource’s degree of scarcity as determined by both demand and supply. And ultimately an input’s price reflects its opportunity cost, or the reward foregone on its next-best use.

Labor and capital are both scarce inputs. Successful integration of AI into the capital stock will make capital more productive, but it will not eliminate the fundamental scarcity of capital. There will always be more use cases than available capital, and particular uses will always have positive opportunity costs.

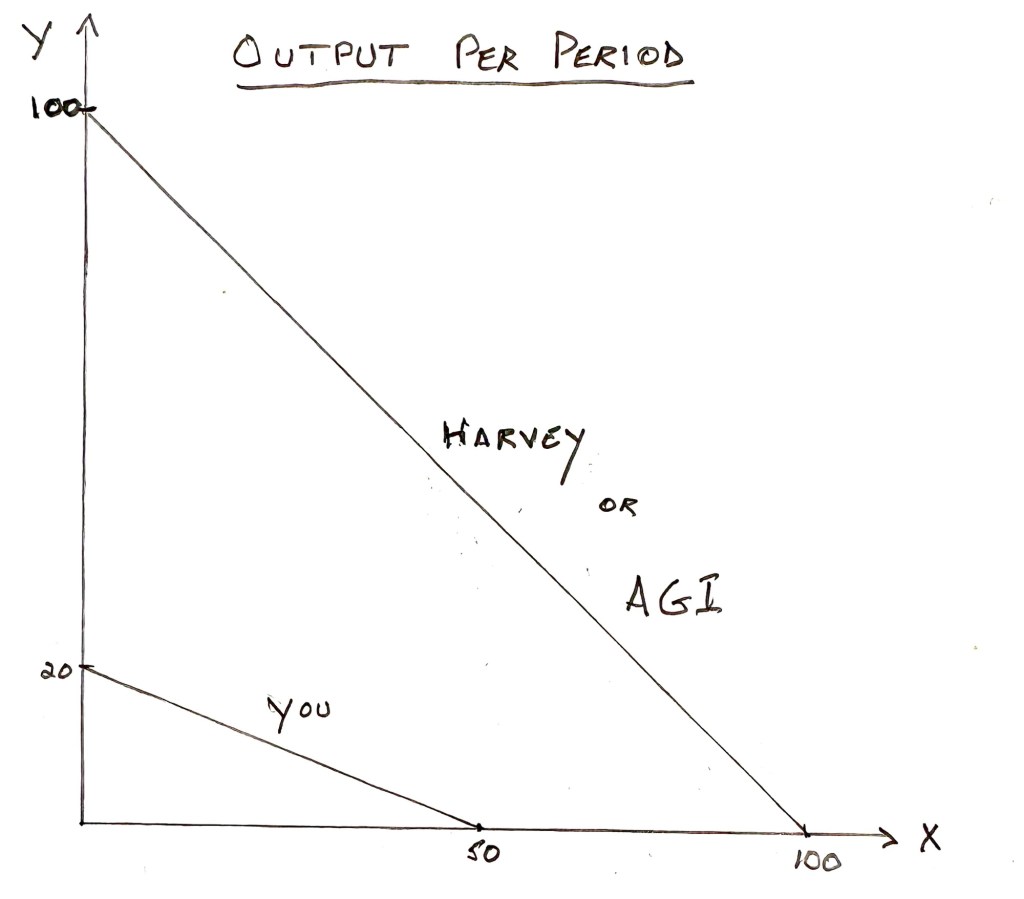

If capital is more productive than labor in a particular use, then capital has an absolute advantage over labor in that line of production. If capital and labor are perfect substitutes in producing good X, then capital can be substituted for labor at a constant rate, say 1 unit of capital for every 2 units of labor, in a straight line without any change in output.

One might expect the producer in this scenario to choose to employ only capital in production. That’s the general argument put forward by AI pessimists. They appeal to a presumed, future absolute advantage of AI (or AI combined with robotics) in each and every line of production. In fact, the pessimists treat the AI robots of the future as perfect substitutes for labor. That’s not a foregone conclusion, however, and even if it were, absolute advantages are not reliable guides to economic decision-making.

Physical tradeoffs in a line of production are one thing, but opportunity costs are another, as they depend on rewards in other lines of production. In the example above, if a unit of capital costs slightly less than two units of labor, then it would indeed be rational to employ all capital and zero labor in producing good X. Then, capital has not just an absolute advantage in X, but also a sufficient cost advantage over labor (or else labor would be more highly valued elsewhere). In this example, the labor share of income from producing X is zero. The capital share is 100%.

Income Shares

The simple case just described is the same as the one examined by Brian Albrecht in his recent analysis of “Capital In the 22nd Century”, an essay by Philip Trammell and Dwarkesh Patel. The controversial conclusion in the latter essay is that capital taxation will be necessary in a world of strong AI, because labor’s share of income will approach zero.

Albrecht is rightfully skeptical. He examines the case of capital and labor as perfect substitutes, as above, and the “corner solution” with all capital and no labor in production.

Albrecht notes that empirical estimates show that capital and labor are not even close to perfect substitutes. In fact, on an economy-wide basis, capital and labor have a fairly high degree of complementarity. But this varies across sectors, and Albrecht acknowledges that substitutability might increase in a world of strong AI.

Without getting ahead of myself, I’ll note here again that AI is likely to dramatically enhance human productivity across tasks. In cases of less than perfect substitution, automation increases the marginal product of labor. In addition, humans benefit from the high degree of complementarities across many tasks, which create limits on deployment opportunities and scaling of AI.

Returns To AI Capital

Albrecht covers a second avenue through which AI-augmented capital could displace labor: rapid growth in the capital stock fueled by stubbornly high returns to capital. While Albrecht’s main interest is in whether capital taxation will one day be necessary, his analysis is obviously a useful reference for thinking about whether labor will be completely displaced by AI-augmented capital.

Again, capital is a scarce resource. For it to grow unbounded in AI-augmented forms, its real yield (and marginal product) must always and forever resist diminishing returns while also exceeding rates of time preference. It also must stay ahead of depreciation on an ever-expanding stock of existing capital. Albrecht is of the opinion that AI-augmented capital might be especially prone to rapid obsolescence. For that matter, it remains to be seen whether the many moving parts of humanoid robots will be highly vulnerable to wear and tear in the field. Perhaps the use of AI in materials research and robotics design can ease those physical constraints.

There are other obstacles to complete AI dominance in the labor market. Institutions of almost all kinds will always face AI deployment risks. On this point, an interesting piece is “Persuasion of Humans Is the Bottleneck”. The author, Erik Schiskin, says that in addition to investment in physical capital:

“AI deployment is capital-intensive in a different way: admissibility—what institutions can rely on, defend, insure, audit, and appeal without taking unbounded tail risk.“

Of course, this too increases the cost of AI deployment.

A “One-Good” Analysis Is Inadequate

Albrecht essentially confines his analysis of inputs and incomes shares to a world in which thee is only one kind of final output, and yet he makes the following assertion:

“Remember this is a model of the whole economy, so that would mean there’s not a single thing produced that humans have a comparative advantage.“

That kind of aggregation is not possible in a world with comparative advantages, however. A mental model with only one good cannot describe a world with opportunity costs. Capital and labor are both scarce resources. Their alternate uses cannot be buried within a single aggregation without appealing to the “idle state” as an alternative use.

With more than one good, the opportunity cost of using an addition unit of capital to produce good X is what must be foregone when that unit of capital is not deployed to its next-best use producing some other good.

And to return to our earlier example, if capital is the exclusive input to the production of Good X, that’s because 1) capital is perfectly substitutable for labor in that line of production; 2) capital is more productive than labor in producing good X; and 3) capital’s relative cost for producing good X is sufficiently low to favor its use.

Factor Intensities

Now I’ll revisit my earlier rationale that for labor’s continuing role in a world with AI-augmented capital. I began to have doubts about how input substitutability might play out as AI is deployed (see other views here and here, as well as Albrecht’s post). So I enlisted the assistance of two AI tools, Grok and ChatGPT, to help identify relevant economic literature bearing on the durability of the “reciprocity” phenomenon given a technical shock. There were differences in the conclusions of the two AI tools when certain embedded assumptions were overlooked or not initially made plain. Considerable push-back against these analyses by yours truly helped to align the conclusions. I’ll be skipping over lots of gory details, but I’d welcome any and all feedback from readers with insight into the issues, or with deeper knowledge of this type of economic research.

Reciprocal input opportunity costs (and comparative advantages) depend on parameters that help determine factor intensity and income shares. A paper by Ronald W. Jones in 1965 helped delineate conditions that preserve the relative rankings of factor intensities across sectors in a closed economy. Those conditions can be extended to the context of reciprocal input opportunity costs. I’ll briefly discuss those conditions in the next couple of sections.

For now, it’s adequate to say that when capital’s comparative advantage in one sector is offset to some degree by a reciprocal comparative advantage for labor in another, we need not conclude that human labor will become obsolete given a positive shock to the productivity of capital. Again, however, in earlier posts I mistakenly asserted that this kind of reciprocity was a more general phenomenon. It is not, and I should have known that. That said, the specifics of the conditions are of interest in the context of AI-augmented capital.

Non-Reciprocity

First, let’s cover cases that are the least conducive to reciprocal opportunity costs: when capital and labor are perfect substitutes in the production of all goods, and when they are perfect complements in the production of all goods. While there are many cases in which inputs are used in fixed proportions in the short run, or where one input can easily be substituted for another in a particular task, it’s still safe to say we don’t generally live in either of those worlds. Nevertheless, they are instructive to consider as extreme cases.

The case of perfect substitutes was discussed above in connection with Albrecht’s post. Then cost minimization yields corner solutions involving 100% capital and zero labor for both goods if capital is everywhere more productive (relative to its cost) than labor. There is no reciprocity of input opportunity costs across goods except by coincidence, and labor will be unemployed.

The other case certain to have non-reciprocal opportunity costs (except by coincidence) is when capital and labor are perfect complements. Then, the rigidity of resource pairings lead to indeterminate input prices and an inability to absorb unemployed resources. However, note that if perfect complementarity were to persist under strong AI, as unlikely as that seems, it would not lead to a capital share of 100%.

A Paradox of Substitutability

Now I turn to more plausible ranges of substitutabilty. There’s a notion that capital with AI enhancements will become more substitutable for labor than it has been historically. And if that’s the case, there’s a fear that humans will be out of work and produce a zero labor share of income. This same line of thinking holds that future prospects for human employment and labor income are better if capital and labor remain somewhat complementary.

That framing of the future of work and its dependence on complementarity vs. substitutability is fairly intuitive. Paradoxically, however, a higher degree of substitutability might not have any impact on human comparative advantages, or might even strengthen them, as long as the elasticity of substitution is not highly asymmetric across sectors.

The Ronald Jones paper referenced above shows that under certain conditions, factor intensities for different goods will retain their relative rankings after a shock to factor prices or technology. By implication, comparative advantages will be preserved as well. So if capital has a greater intensity in producing X than in producing Y, that ranking must preserved after a shock if capital and labor are to retain their reciprocal comparative advantages. Jones shows this is satisfied when the inputs in both sectors are equally substitutable, or when changes in substitutability across sectors are equal. If those changes are not greatly different, then reversals in factor intensity are unlikely and reciprocity is usually preserved. Therefore, if augmenting capital with AI increases the elasticity of substitutability between capital and labor broadly, there is a good chance that many reciprocal comparative advantages will be preserved.

Another general guide implied by the Jones paper is that factor intensities and reciprocal comparative advantages are more likely to be preserved when production technologies differ, input proportions are stable, and differences in substitutability are similar or differ only moderately.

Empirically, elasticities of substitution between capital and labor vary across industries but are typically well within a range of complementarity (0.3 to 0.7). Starting from these positions, and given increases in substitutability via AI-augmented capital, factor proportions aren’t likely to change drastically, and rankings of capital intensity aren’t likely to be altered greatly, thus preserving comparative advantages for most sectors.

Restating the Last Section

Starting from a world in which inputs have reciprocal comparative advantages (and reciprocal opportunity costs), a technological advance like the augmentation of capital via AI might or might not preserve reciprocity. The return on capital will increase, and widespread capital deepening is likely to drive up the rental rate of a unit of capital relative to its higher marginal product. If capital intensities increase in all sectors, but relative rankings of capital intensities are preserved, then labor will retain comparative advantages despite the possible absolute advantages of AI-augmented capital. Labor’s share of income will certainly not fall to zero.

If the substitutability of capital and labor increase, ongoing reciprocity can be preserved if the change in substitutability does not differ greatly across sectors. This is true even for large, but broad, increases in substitutability. However, should large increases in substitutability be concentrated to some sectors but not others, reciprocity could fail more broadly. If greater substitutability implies greater dispersion in substitutabilities, then reciprocity is likely to be less stable.

Of course, regardless of the considerations above, there are certain to disruptions in the labor market. Classes of workers will be forced to leverage AI themselves, find new occupations, or reprice their services. Nevertheless, once the dynamics have played out, labor will still have a significant role in production.

Recapping the Whole Post

Here are a few things we know:

Capital will remain scarce, even more so if its return reaches impressive heights via AI augmentation. Another way of saying this is that interest rates would have to rise in order to induce saving. Depreciation and obsolescence of capital will reinforce that scarcity, and there are now and always will be too many valued uses for capital to become a free good.

Capital and labor are not perfect substitutes in most tasks and probably won’t be, even given strong AI-augmentation.

Capital and labor are not perfect complements, though they have been complementary historically. Their complementarity might well be moderated by AI.

Besides capital scarcity, there will be a continuing series of bottlenecks to AI deployment, some of which will demand human involvement.

We start our transition to a world of AI-augmented capital with different inputs having comparative advantages in producing some goods and not others. In general, at the outset, there is a reciprocity of input comparative advantages and opportunity costs across sectors, much as reciprocal opportunity costs exist in cross-country trade relationships.

A technological shock like the introduction of strong AI will alter these relationships. However, as long as factor intensities in different sectors maintain their rank ordering, reciprocal opportunity costs will still exist.

If substitutability increases with the introduction of AI-augmented capital, reciprocal opportunity costs will be preserved as long as the changes in the degree of substitutability do not differ greatly across sectors.

My earlier contention that reciprocal opportunity costs were the rule was incorrect. However, it’s safe to say that reciprocity will persist to one degree or another, even if more weakly, as the transition to AI goes forward. That means labor will still have a role in production, despite many areas in which AI-augmented capital will have an absolute advantage. And we haven’t even discussed preferences for “the human touch” and the likelihood that AI will spawn new opportunities for human labor as yet unimagined.