Tags

Bolsheviks, Class Struggle, Das Kapital, Das Karl Marx Problem, Fidel Castro, Google Ngram, John Maynard Keynes, Josef Stalin, Karl Marx, Labor Theory of Value, Lenin, Marxism, Michael Makovi, Phil Magness, Philip Hobsbawm, Pol Pot, Workers’ Paradise

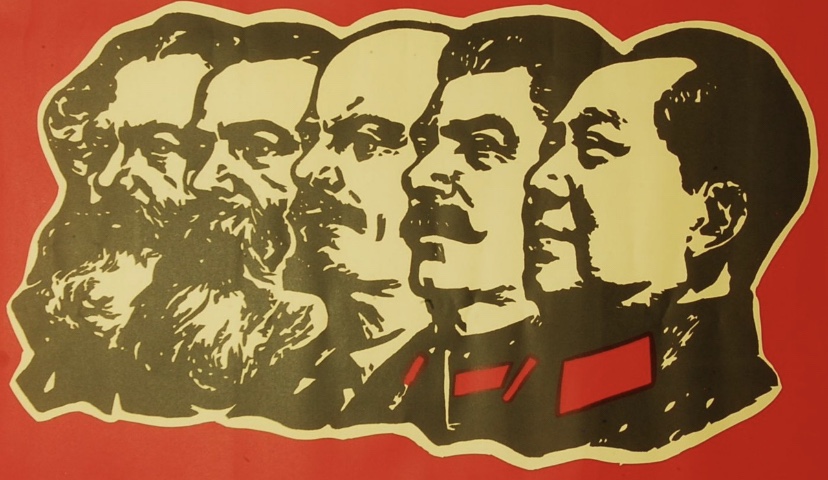

Karl Marx has long been celebrated by the Left as a great intellectual, but the truth is that his legacy was destined to be of little significance until his writings were lauded, decades later, by the Bolsheviks during their savage October 1917 revolution in Russia. Vladimir Lenin and his murderous cadre promoted Marx and brought his ideas into prominence as political theory. That’s the conclusion of a fascinating article by Phil Magness and Michael Makovi (M&M) appearing in the Journal of Political Economy. The title: “The Mainstreaming of Marx: Measuring the Effect of the Russian Revolution on Karl Marx’s Influence“.

The idea that the early Soviet state and other brutal regimes in its mold were the main progenitors of Marxism is horrifying to its adherents today. That’s the embarrassing historical reality, however. It’s not really clear that Marx himself would have endorsed those regimes, though I hesitate to cut him too much slack.

A lengthy summary of the M&M paper is given by the authors in “Das Karl Marx Problem”. The “problem”, as M&M describe it, is in reconciling 1) the nearly complete and well-justified rejection of Marx’s economic theories during his life and in the 34 years after his death, with 2) the esteem in which he’s held today by so many so-called intellectuals. A key piece of the puzzle, noted by the authors, is that praise for Marx comes mainly from outside the economics profession. The vast majority of economists today recognize that Marx’s labor theory of value is incoherent as an explanation of the value created in production and exchange.

The theoretical rigors might be lost on many outside the profession, but a moments reflection should be adequate for almost anyone to realize that value is contributed by both labor and non-labor inputs to production. Of course, it might have dawned on communists over the years that mass graves can be dug more “efficiently” by combining labor with physical capital. On the other hand, you can bet they never paid market prices for any of the inputs to that grisly enterprise.

Marx never thought in terms of decisions made at the margin, the hallmark of the rational economic actor. That shortcoming in his framework led to mistaken conclusions. Second, and again, this should be obvious, prices of goods must incorporate (and reward) the value contributed by all inputs to production. That value ultimately depends on the judgement of buyers, but Marx’s theory left him unable to square the circle on all this. And not for lack of trying! It was a failed exercise, and M&M provide several pieces of testimony to that effect. Here’s one example:

“By the time Lenin came along in 1917, Marx’s economic theories were already considered outdated and impractical. No less a source than John Maynard Keynes would deem Marx’s Capital ‘an obsolete economic textbook . . . without interest or application for the modern world’ in a 1925 essay.”

Marxism, with its notion of a “workers’ paradise”, gets credit from intellectuals as a highly utopian form of socialism. In reality, it’s implementation usually takes the form of communism. The claim that Marxism is “scientific” socialism (despite the faulty science underlying Marx’s theories) is even more dangerous, because it offers a further rationale for authoritarian rule. A realistic transition to any sort of Marxist state necessarily involves massive expropriations of property and liberty. Violent resistance should be expected, but watch the carnage when the revolutionaries gain the upper hand.

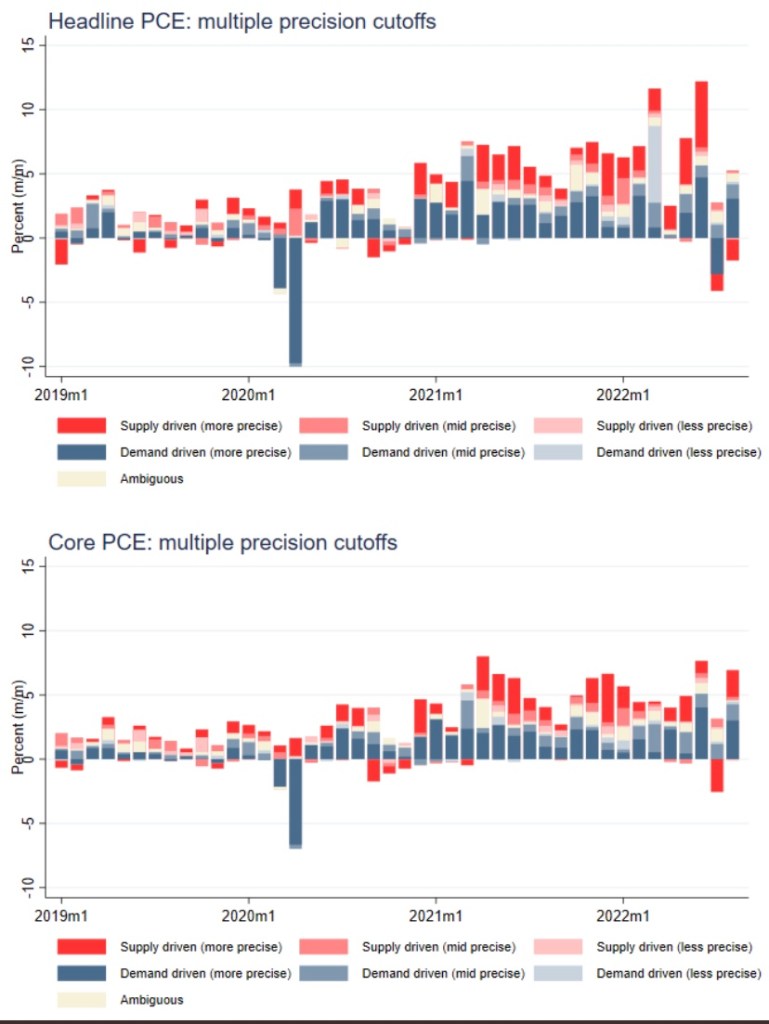

What M&M demonstrate empirically is how lightly Marx was cited or mentioned in printed material up until 1917, both in English and German. Using Google’s Ngram tool, they follow a group of thinkers whose Ngram patterns were similar to Marx’s up to 1917. They use those records to construct an expected trajectory for Marx for 1917 forward and find an aberrant jump for Marx at that time, again both in English and in German material. But Ngram excludes newspaper mentions, so they also construct a database from Newspapers.com and their findings are the same: newspaper references to Marx spiked after 1917. There was nothing much different when the sample was confined to socialist writers, though M&M acknowledge that there were a couple of times prior to 1917 during which short-lived jumps in Marx citations occurred among socialists.

To be clear, however, Marx wasn’t unknown to economists during the 3+ decades following his death. His name was mentioned here and there in the writings of prominent economists of the day — just not in especially glowing terms.

“… absent the events of 1917, Marx would have continued to be an object of niche scholarly inquiry and radical labor activism. He likely would have continued to compete for attention in those same radical circles as the main thinker of one of its many factions. After the Soviet boost to Marx, he effectively crowded the other claimants out of [the] socialist-world.”

Magness has acknowledged that he and Makovi aren’t the first to have noticed the boost given to Marx by the Bolsheviks. Here, Magness quotes Eric Hobsbawm’s take on the subject:

“This situation changed after the October Revolution – at all events, in the Communist Parties. … Following Lenin, all leaders were now supposed to be important theorists, since all political decisions were justified on grounds of Marxist analysis – or, more probably, by reference to textual authority of the ‘classics’: Marx, Engels, Lenin, and, in due course, Stalin. The publication and popular distribution of Marx’s and Engels’s texts therefore become far more central to the movement than they had been in the days of the Second International [1889 – 1914].”

Much to the chagrin of our latter day Marxists and socialists, it was the advent of the monstrous Soviet regime that led to Marx’s “mainstream” ascendency. Other brutal regimes arising later reinforced Marx’s stature. The tyrants listed by M&M include Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro, and Pol Pot, and they might have added several short-lived authoritarian regimes in Africa as well. Today’s Marxists continue to assure us that those cases are not representative of a Marxist state.

Perhaps it’s fair to say that Marx’s name was co-opted by thugs, but I posit something a little more consistent with the facts: it’s difficult to expropriate the “means of production” without a fight. Success requires massive takings of liberty and property. This is facilitated by means of a “class struggle” between social or economic strata, or it might reflect divisions based on other differences. Either way, groups are pitted against one another. As a consequence, we witness an “othering” of opponents on one basis or another. Marxists, no matter how “pure of heart”, find it impossible to take power without demanding ideological purity. Invariably, this requires “reeducation”, cleansing, and ultimately extermination of opponents.

Karl Marx had unsound ideas about how economic value manifests and where it should flow, and he used those ideas to describe what he thought was a more just form of social organization. The shortcomings of his theory were recognized within the economics profession of the day, and his writings might have lived on in relative obscurity were it not for the Bolshevik’s intellectual pretensions. Surely obscurity would have been better than a legacy shaped by butchers.