Tags

Car Dependence, Cloverleaf Interchanges, Congestion pricing, Diamond Interchange, Diverging Diamond, Dynamic Pricing, Failure of the Commons, Flyover Ramps, Gas Taxes, Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, Interstate Highways, Jessica Trounstine, Joe Biden, Joel Kotkin, Lyft, New York City, Paved Paradise, Private Roads, Reddit, Robert P. Murphy, Sarasota, Socialized Roads, SunPass, Tolls, Uber, Urban planning, Urban Sprawl, Willian Frey

The interchange above is just a few miles from my new home. It’s the world’s largest “diverging diamond” design and it usually works quite well, so I was interested to see this video discussing both its benefits and the conditions under which it hasn’t performed well.

Unfortunately, the video maintains a dubious focus on car dependence in most urban areas. The tale it tells is daunting… and if the reaction on Reddit is any indication, it seems to excite the populist mind. The narrator blames car dependence and sprawl on poor urban planning. I agree in a sense, and I’ll even stipulate that our car dependence is often excessive, but not because anyone could have “planned” better. Top-down planning is notoriously failure-prone. Rather, the corrective is something the creators of the video never contemplate: effective pricing for the use of roads.

There is deserved emphasis near the end of the video on the cost of building and maintaining roads and interchanges. For example, the cost of the interchange above was $74.5 million when it was built about 15 years ago. That sounds exorbitant, and it’s natural for people (and especially urban planners) to question the necessity of building an interchange of that magnitude in what many feel “should be” an outlying district. Did sprawl make it necessary? Can that be avoided in a growing region? What can or should be done?

Good Interchange Design

The interchange in question is at I-75 and University Parkway in Sarasota, FL. It’s used by many drivers to access a large shopping mall, other commercial centers, and nearby residential areas. The video stresses the diverging diamond’s effectiveness and safety in handling high flows of traffic. The design reduces the number of conflict points relative to conventional diamond interchanges, especially for crossing traffic.

Both diverging diamonds and conventional diamond interchanges have advantages over cloverleaf designs. While the latter have no crossover conflict points, they require more land use. They also create additional complexities for grading and drainage, and they are often constrained in the length of space available for left-turn merges. Furthermore, a cloverleaf places more severe limits on traffic flow. Flyover ramps are another alternative that can save space but entail greater expense.

The interchange in question serves an area of rapid growth. Residents increasingly complain about traffic, especially when “snow birds” are in town during the winter months. The video shows that even the diverging diamond has problems once traffic reaches a certain volume. But new residential communities and commercial areas continue to come on-line, adding to traffic flows and requiring additional roads and infrastructure. Again, the narrator believes the resulting traffic and sprawl could have been avoided, and he’s partly correct as far as that goes.

Sprawl Reflects Preferences

The video fails to consider important qualifications to the “car dependence” critique of suburban sprawl. For example, many people like to use their cars and enjoy the freedom of mobility their cars confer. More importantly, most people prefer to live in low-density residential environments rather than dense urban neighborhoods, or even the kinds of communities depicted as ideal in the video. I’m one of those people. More space, more privacy, and more greenery (though I grant that sprawling mall parking lots are not my favorite aesthetic).

Joel Kotkin presents data along those lines, quoting research by Jessica Trounstine, who says, “preferences for single-family development are ubiquitous.” And low-density communities have broad appeal across demographics, as noted by Kotkin:

“Even in blue states, the majority of ethnic minorities live in suburbs, who have accounted for virtually all the suburban growth over the past decade. William Frey of the Brookings Institution notes that in 1990 roughly 20 percent of suburbanites were non-white. That rose to 30 percent in 2000 and 45 percent in 2020.”

Urban Planning Myopia

As to the video’s emphasis on car dependence, its most serious omission is a failure to recognize the economics of pricing. Road use comes with various costs, but the key here is the zero price at the margin for using specific routes, interchanges, bridges, and suburban parking lots. There are many exceptions to be sure, but the video makes no mention of road pricing as a development tool. Nor does it consider “socialized roads” as the chief cause of ever-expanding demands for roads, parking, and the all-too-typical failure of these ersatz “commons”.

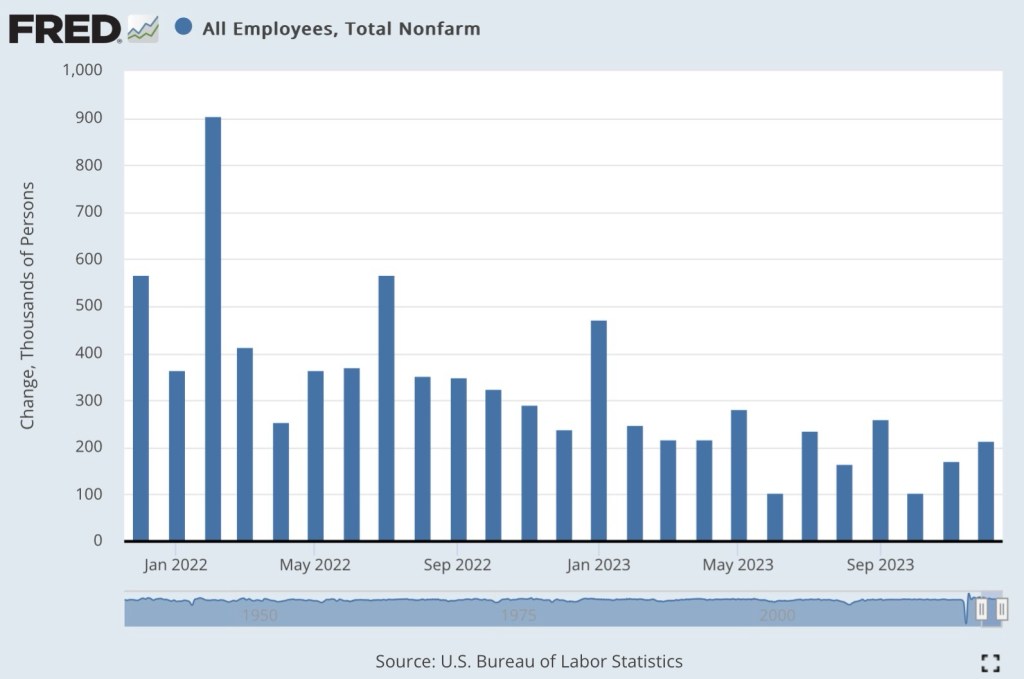

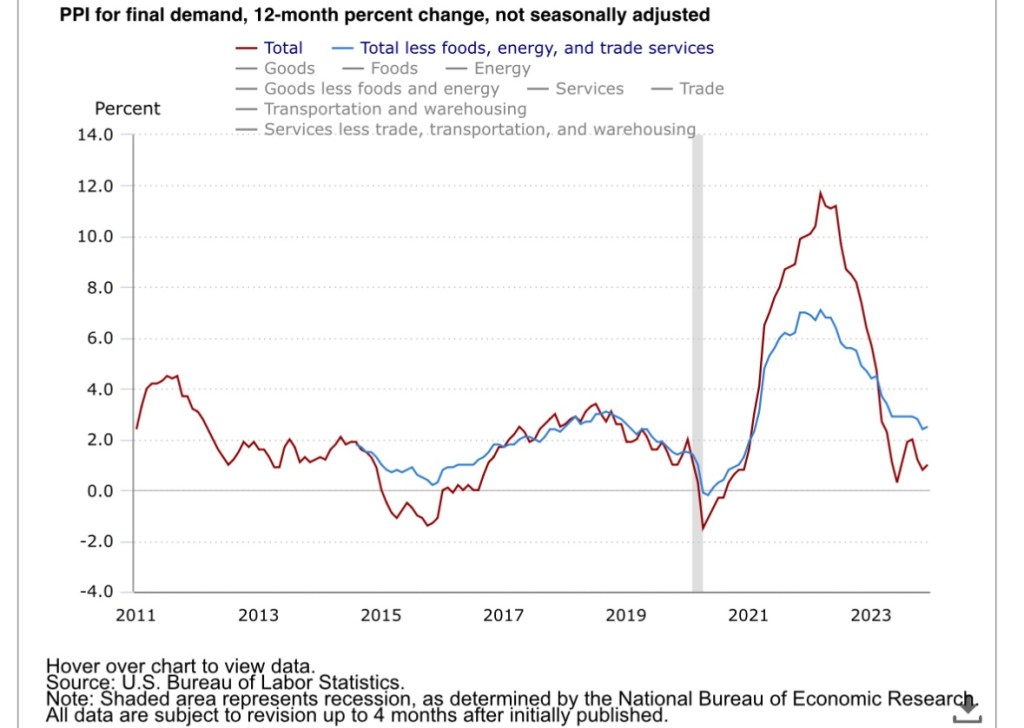

The federal government is complicit in this. After all, the interstate highway system was a federal initiative, and interchanges (along with concomitant commercial development) are integral to its success. Interstate highways often supplemented regional efforts to facilitate commuting to cities from distant suburbs. More recently, Joe Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 added $110 billion a year from the government’s general fund to subsidize highways and bridges. It should be no surprise that federal gas taxes don’t fund these subsidies. (Gas taxes are user fees only in a vague sense, as they don’t price specific routes at the margin).

More Roads, Trains, Buses?

There are two knee-jerk reactions to congested roads. The first is a tendency to double-down on invested plant, building more, bigger, and wider roads in the hope that they can handle the growing traffic load. Presumably this must be funded by taxpayers, as in the past, and seldom if ever by charging per marginal use of these facilities. This “solution” basically calls for more socialized roads.

The second knee-jerk reaction to congestion, and it is also a reaction to the real or presumed shortcomings of a “paved paradise”, is to call for more buses, streetcars, or light rail. But mass transit systems seldom pay for their operating costs let alone their capital costs. One of the reasons, of course, is that they must compete with free roads!

What else might the urban planners have us do? We can’t just tear down the sprawling developments and road infrastructure and start over. However, we can accomplish a few other things like: 1) raise revenue from users to make the upkeep of road infrastructure self-funding; 2) minimize congestion, emissions, and time-use while improving safety; and 3) stem growth in demand that eventually would require more lanes, more parking, and other measures to maximize traffic flow. Pricing the actual use of roads would do all these things in greater or lesser degree, and it would more effectively balance development preferences with costs. In turn, positive road-use prices would incentivize other development models such as the “human-centric” communities the video’s narrator finds so attractive.

Those Who Benefit Shall Pay

Tolls for the use of roads and bridges (and paid parking) are hardly new ideas. Tolls on bridges were a natural continuation of fees charged by operators of ferry boats. Tolling was instituted by large landholders to extract rents from anyone wishing to traverse their property, and only later was used as a mechanism for funding road construction and maintenance. But like any price, tolls serve to ration the availability of a resource.

Today, tolling in the U.S. is an increasingly important source of funding for highways and bridges. This importance is growing due to a less sanguine outlook for gas tax collections. In any case, tolls are often more advantageous politically than taxes. Technological advance has allowed tolling to become more cost effective as well. In Florida, for example, the SunPass system allows drivers to cruise through toll collection points at moderate speeds. It’s also used for parking at certain facilities like airports. SunPass holders are required to set up automatic “recharge” of their available balance for toll payments. Similar systems are in place in other states.

Technology has enabled dynamic congestion pricing to be implemented by commercial interests like Uber and Lyft. This means that price responds to demand and supply conditions in real time. In coming years, congestion pricing is likely to be instituted by jurisdictions experiencing heavy traffic volumes. New York City’s congestion pricing plan has stalled, but it would charge a toll on vehicles using Manhattan streets below Central Park.

Law of Demand

Tolls at interchanges like the one at I-75 and University Parkway would help to allocate resources more efficiently. First, the mechanics could be simple enough in concept, but toll booths are probably out of the question, and toll authorities would have to sort through various administrative issues.

Let’s suppose SunPass was put to use here, with the revenue distributed to several jurisdictions or agencies responsible for maintaining the interchange and a defined set of connecting streets. When a driver exits I-75 to University, enters I-75 from University, or uses the through lanes on University, the SunPass transponder in their vehicle would communicate with the toll system to record their passage, and their account would be charged the appropriate toll. The charge might differ for through lanes versus I-75 entry or exit. Over the course of a month, tolls on various roads and interchanges would accumulate and be summarized by road or interchange on a statement for the driver.

Vehicles without SunPass (or another toll system partnering with SunPass) would have to be charged via photo identification of tags with billing by mail once a month. This is already a feature of toll roads in Florida (and other states) when vehicles without a SunPass use the SunPass lanes. The volume of mail billing would increase substantially, but that is not an obstacle in principle.

One other wrinkle would allow existing residents of neighborhoods with street entrances within one or two miles of the interchange to receive discounted tolls. That seems fair, but the danger is that discounts of this kind, if extended too far, would blunt incentives that otherwise discourage overuse and underpriced road sprawl. It would also add another layer of complexity to the tolling system.

The behavior of drivers will change in response to tolls. They derive benefits from using particular interchanges which depend upon the importance of errands or appointments in each vicinity, the distance and convenience of other shopping areas, the time of day, and the time saved by using any one route instead of alternates. The toll paid for using an interchange might depend on the size of vehicle, the time of day, or some measure of average congestion at that time of day. A higher toll prompts drivers to consider other routes, other shopping areas (including on-line shopping), or different times of day for those errands. Thus, tolls will redistribute traffic across space and time and are likely to reduce overall traffic at the most congested interchanges, at least at peak hours when tolls are highest.

Smart Pricing

The advent and installation of more sophisticated tolling infrastructure will enable “smart roads”, time-of-day pricing, or even dynamic congestion pricing on some routes. Integrating dynamic pricing with information systems guiding driver decisions about route choice and timing would be another major step. Implementing sophisticated route pricing systems like this will take time, but ultimately the technology will allow tolls to be applied broadly and efficiently… if we allow it to happen.

Private Vs. Public

The private sector is likely to play a greater role in a world of more widespread tolling. To some extent this will take the form of more privately-owned roads. Short of that, many toll roads and smart roads will be privately administered and operated. Private concerns will also play a major role in provisioning infrastructure and systems for more widespread and sophisticated toll roads.

There is a long history of private roads in the U.S. Robert P. Murphy offers a brief summary:

“… many analysts simply assume, because currently the government virtually monopolizes the production and administration of roads, that it must always have done so. And yet, from the 1790s through the 1830s, the private sector was responsible for the creation and operation of many turnpikes. According to economist Daniel Klein, ‘The turnpike companies were legally organized like corporate businesses of the day. The first, connecting Philadelphia and Lancaster, was chartered in 1792, opened in 1794, and proved significant in the competition for trade.’3 ‘By 1800,’ Klein reports, ‘sixty-nine companies had been chartered’ in New England and the Middle Atlantic states. Merchants would often underwrite the expense of building a turnpike, knowing that it would bring in extra traffic to their businesses.”

In Norway and Sweden, most roads are owned and operated privately, though most of the private roads are local. The funding is generally provided by property owners along those routes. Private roads are increasingly common in the U.S., but they are mostly confined to private communities funded by residents. Broader private ownership of roads, and tolling, is likely to occur in the U.S. as governments at all levels struggle with issues of funding, maintenance, traffic control, and growth.

Pricing For Scarcity

There will be political obstacles to widespread tolling and road congestion pricing. Questions of equity and privacy will be raised, but pricing may hold the key to achieving more equitable outcomes. Greater reliance on tolls would avoid regressive tax increases, and selective tolls themselves might well have a progressive incidence, to the extent that congestion tends to be high in prosperous commercial districts. It would make alternatives like mass transit more competitive and viable as well. Furthermore, price signals will cause geographic patterns of commerce and development to shift, potentially encouraging the kinds of high-density, pedestrian communities long-favored by urban planners.

Urban sprawl and auto dependence are old targets of the urban planning community, not to mention the populist left. But those critics rely on a stylized characterization of geographic and social arrangements that happen to be preferred by masses of individuals. As an economist, I sympathize with the critics because those preferences are revealed under incentives that do not reflect the scarcity and real costs of roads and driving. However, in the absence of adequate price incentives, solutions offered by critics of sprawl and autos are at worst brutally intrusive and at best ineffectual. More efficient pricing of roads can be achieved with the installation of tolling solutions that are now technologically feasible. Optimizing tolls over specific roads, bridges, blocks, intersections, and interchanges will require more sophisticated systems, but for now, let’s at least get road-use prices going in the right direction!