Tags

3-D Printing, Artificial Intelligence, Automation, David Henderson, Don Boudreaux, Great Stagnation, Herbert Simon, Human Augmentation, Industrial Revolution, Marginal Revolution, Mass Unemployment, Matt Ridley, Russ Roberts, Scarcity, Skills Gap, Transition Costs, Tyler Cowan, Wireless Internet

Machines have always been regarded with suspicion as a potential threat to the livelihood of workers. That is still the case, despite the demonstrated power of machines make life easier and goods cheaper. Today, the automation of jobs in manufacturing and even service jobs has raised new alarm about the future of human labor, and the prospect of a broad deployment of artificial intelligence (AI) has made the situation seem much scarier. Even the technologists of Silicon Valley have taken a keen interest in promoting policies like the Universal Basic Income (UBI) to cushion the loss of jobs they expect their inventions to precipitate. The UBI is an idea discussed in last Sunday’s post on Sacred Cow Chips. In addition to the reasons for rejecting that policy cited in that post, however, we should question the premise that automation and AI are unambiguously job killing.

The same stories of future joblessness have been told for over two centuries, and they have been wrong every time. The vulnerability in our popular psyche with respect to automation is four-fold: 1) the belief that we compete with machines, rather than collaborate with them; 2) our perpetual inability to anticipate the new and unforeseeable opportunities that arise as technology is deployed; 3) our tendency to undervalue new technologies for the freedoms they create for higher-order pursuits; and 4) the heavy discount we apply to the ability of workers and markets to anticipate and adjust to changes in market conditions.

Despite the technological upheavals of the past, employment has not only risen over time, but real wages have as well. Matt Ridley writes of just how wrong the dire predictions of machine-for-human substitution have been. He also disputes the notion that “this time it’s different”:

“The argument that artificial intelligence will cause mass unemployment is as unpersuasive as the argument that threshing machines, machine tools, dishwashers or computers would cause mass unemployment. These technologies simply free people to do other things and fulfill other needs. And they make people more productive, which increases their ability to buy other forms of labour. ‘The bogeyman of automation consumes worrying capacity that should be saved for real problems,’ scoffed the economist Herbert Simon in the 1960s.“

As Ridley notes, the process of substituting capital for labor has been more or less continuous over the past 250 years, and there are now more jobs, and at far higher wages, than ever. Automation has generally involved replacement of strictly manual labor, but it has always required collaboration with human labor to one degree or another.

The tools and machines we use in performing all kinds of manual tasks become ever-more sophisticated, and while they change the human role in performing those tasks, the tasks themselves largely remain or are replaced by new, higher-order tasks. Will the combination of automation and AI change that? Will it make human labor obsolete? Call me an AI skeptic, but I do not believe it will have broad enough applicability to obviate a human role in the production of goods and services. We will perform tasks much better and faster, and AI will create new and more rewarding forms of human-machine collaboration.

Tyler Cowen believes that AI and automation will bring powerful benefits in the long run, but he raises the specter of a transition to widespread automation involving a lengthy period of high unemployment and depressed wages. Cowen points to a 70-year period for England, beginning in 1760, covering the start of the industrial revolution. He reports one estimate that real wages rose just 22% during this transition, and that gains in real wages were not sustained until the 1830s. Evidently, Cowen views more recent automation of factories as another stage of the “great stagnation” phenomenon he has emphasized. Some commenters on Cowen’s blog, Marginal Revolution, insist that estimates of real wages from the early stages of the industrial revolution are basically junk. Others note that the population of England doubled during that period, which likely depressed wages.

David Henderson does not buy into Cowans’ pessimism about transition costs. For one thing, a longer perspective on the industrial revolution would undoubtedly show that average growth in the income of workers was dismal or nonexistent prior to 1760. Henderson also notes that Cowen hedges his description of the evidence of wage stagnation during that era. It should also be mentioned the share of the U.S. work force engaged in agricultural production was 40% in 1900, but is only 2% today, and the rapid transition away from farm jobs in the first half of the 20th century did not itself lead to mass unemployment nor declining wages (HT: Russ Roberts). Cowen cites more recent data on stagnant median income, but Henderson warns that even recent inflation adjustments are fraught with difficulties, that average household size has changed, and that immigration, by adding households and bringing labor market competition, has had at least some depressing effect on the U.S. median wage.

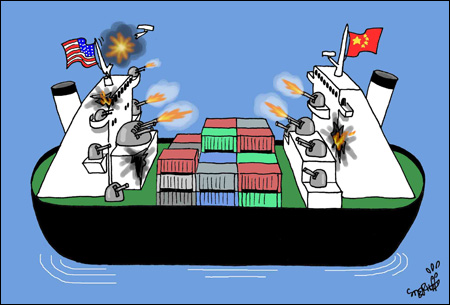

Even positive long-run effects and a smooth transition in the aggregate won’t matter much to any individual whose job is easily automated. There is no doubt that some individuals will fall on hard times, and finding new work might require a lengthy search, accepting lower pay, or retraining. Can something be done to ease the transition? This point is addressed by Don Boudreaux in another context in “Transition Problems and Costs“. Specifically, Boudreaux’s post is about transitions made necessary by changing patterns of international trade, but his points are relevant to this discussion. Most fundamentally, we should not assume that the state must have a role in easing those transitions. We don’t reflexively call for aid when workers of a particular firm lose their jobs because a competitor captures a greater share of the market, nor when consumers decide they don’t like their product. In the end, these are private problems that can and should be solved privately. However, the state certainly should take a role in improving the function of markets such that unemployed resources are absorbed more readily:

“Getting rid of, or at least reducing, occupational licensing will certainly help laid-off workers transition to new jobs. Ditto for reducing taxes, regulations, and zoning restrictions – many of which discourage entrepreneurs from starting new firms and from expanding existing ones. While much ‘worker transitioning’ involves workers moving to where jobs are, much of it also involves – and could involve even more – businesses and jobs moving to where available workers are.“

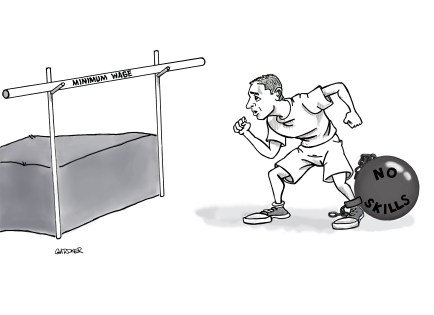

Boudreaux also notes that workers should never be treated as passive victims. They are quite capable of acting on their own behalf. They often act out of risk avoidance to save their funds against the advent of a job loss, invest in retraining, and seek out new opportunities. There is no question, however, that many workers will need new skills in an economy shaped by increasing automation and AI. This article discusses some private initiatives that can help close the so-called “skills gap”.

Crucially, government should not accelerate the process of automation beyond its natural pace. That means markets and prices must be allowed to play their natural role in directing resources to their highest-valued uses. Unfortunately, government often interferes with that process by imposing employment regulations and wage controls — i.e., the minimum wage. Increasingly, we are seeing that many jobs performed by low-skilled workers can be automated, and the expense of automation becomes more worthwhile as the cost of labor is inflated to artificial levels by government mandate. That point was emphasized in a 2015 post on Sacred Cow Chips entitled “Automate No Job Before Its Time“.

Another past post on Sacred Cow Chips called “Robots and Tradeoffs” covered several ways in which we will adjust to a more automated economy, none of which will require the intrusive hand of government. One certainty is that humans will always value human service, even when a robot is more efficient, so there will be always be opportunities for work. There will also be ways in which humans can compete with machines (or collaborate more effectively) via human augmentation. Moreover, we should not discount the potential for the ownership of machines to become more widely dispersed over time, mitigating the feared impact of automation on the distribution of income. The diffusion of specific technologies become more widespread as their costs decline. That phenomenon has unfolded rapidly with wireless technology, particularly the hardware and software necessary to make productive use of the wireless internet. The same is likely to occur with 3-D printing and other advances. For example, robots are increasingly entering consumer markets, and there is no reason to believe that the same downward cost pressures won’t allow them to be used in home production or small-scale business applications. The ability to leverage technology will require learning, but web-enabled instruction is becoming increasingly accessible as well.

Can the ownership of productive technologies become sufficiently widespread to assure a broad distribution of rewards? It’s possible that cost reductions will allow that to happen, but broadening the ownership of capital might require new saving constructs as well. That might involve cooperative ownership of capital by associations of private parties engaged in diverse lines of business. Stable family structures can also play a role in promoting saving.

It is often said that automation and AI will mean an end to scarcity. If that were the case, the implications for labor would be beside the point. Why would anyone care about jobs in a world without want? Of course, work might be done purely for pleasure, but that would make “labor” economically indistinguishable from leisure. Reaching that point would mean a prolonged process of falling prices, lifting real wages on a pace matching increases in productivity. But in a world without scarcity, prices must be zero, and that will never happen. Human wants are unlimited and resources are finite. We’ll use resources more productively, but we will always find new wants. And if prices are positive, including the cost of capital, it is certain that demands for labor will remain.