Tags

Bronze Age, central planning, Client-Server Network, Decentralized Decision-Making, Economies of Scale, Federalism, Francis Turner, Industrial Policy, Liberty.me, Markets, Peer-to-Peer Network, Price mechanism, Property Rights, Scalability, Spontaneous Order

The proposition that mankind is capable of creating a successful “planned” society is at least as old as the Bronze Age. Of course it’s been tried. The effort necessarily involves a realignment of the economic and political landscape and always requires a high degree of coercion. But putting that aside, such planning can never be successful relative to spontaneous order of the kind that dominates private affairs in a free society. The task of advancing human well-being given available resources has never been achieved under central planning. It always fails miserably in this regard, and it always will fail to match the success of decentralized decision-making and private markets.

There are various ways to explain this fact, but I recently came across an interesting take on the subject having to do with the notion of scalability. Francis Turner offers this note on the topic at the Liberty.me blog. To begin, he gives a lengthy quote from a software developer who relates the problems of social and economic planning to the complexity of managing a network. On the topic of scale, the developer notes that the number of relationships in a network increases with the square of the number of its “nodes”, or members:

“2 nodes have 1 potential relationship. 4 nodes (twice as many) has 6 potential relationships (6 times as many). 8 nodes (twice again) has 28 potential relationships. 100 nodes => [4,950] relationships; 1,000 nodes => 499,500 relationships—nearly half a million.“

Actually, the formula for the number of potential relationships or connections in a network is n*(n-1)/2, where n is the number of network nodes. The developer Turner quotes discusses this in the context of two competing network management structures: client-server and peer-to-peer. Under the former, the network is managed centrally by a server, which communicates with all nodes, makes various decisions, and routes communications traffic between nodes. In a peer-to-peer network, the work of network management is distributed — each computer manages its own relationships. The developer says, at first, “the idea of hooking together thousands of computers was science fiction.” But as larger networks were built-out in the 1990s, the client-server framework was more or less rejected by the industry because it required such massive resources to manage large networks. In fact, as new nodes are added to a peer-to-peer network, its capacity to manage itself actually increases! In other words, client-server networks are not as scalable as peer-to-peer networks:

“Even if it were perfectly designed and never broke down, there was some number of nodes that would crash the server. It was mathematically unavoidable. You HAVE TO distribute the management as close as possible to the nodes, or the system fails.

… in an instant, I realized that the same is true of governments. … And suddenly my coworker’s small government rantings weren’t crazy…”

This developer’s epiphany captures a few truths about the relative efficacy of decentralized decision-making. It’s not just for computer networks! But in fact, when it comes to network management, the task is comparatively simple: meet the computing and communication needs of users. A central server faces dynamic capacity demands and the need to route changing flows of traffic between nodes. Software requirements change as well, which may necessitate discrete alterations in capacity and rules from time-to-time.

But consider the management of a network of individual economic units. Let’s start with individuals who produce something… like widgets. There are likely to be real economies achieved when a few individual widgeteers band together to produce as a team. Some specialization into different functions can take place, like purchasing materials, fabrication, and distribution. Perhaps administrative tasks can be centralized for greater efficiency. Economies of scale may dictate an even larger organization, and at some point the firm might find additional economies in producing widget-complementary products and services. But eventually, if the decision-making is centralized and hierarchical, the sheer weight of organizational complexity will begin to take a toll, driving up costs and/or diminishing the firm’s ability to deal with changes in technology or the market environment. In other words, centralized control becomes difficult to scale in an efficient way, and there may be some “optimal” size for a firm beyond which it struggles.

Now consider individual consumers, each of whom faces an income constraint and has a set of tastes spanning innumerable goods. These tastes vary across time scales like hour-of-day, day-of-week, seasons, life-stage, and technology cycles. The volume of information is even more daunting when you consider that preferences vary across possible price vectors and potential income levels as well.

Can the interactions between all of these consumer and producer “nodes” be coordinated by a central economic authority so as to optimize their well-being dynamically, subject to resource constraints? As we’ve seen, the job requires massive amounts of information and a crushing number of continually evolving decisions. It is really impossible for any central authority or computer to “know” all of the information needed. Secondly, to the software developer’s point, the number of potential relationships increases with the square of the number of consumers and producers, as does the required volume of information and number of decisions. The scalability problem should be obvious.

This kind of planning is a task with which no central authority can keep up. Will the central authority always get milk, eggs and produce to the store when people need it, at a price they are willing to pay, and with minimal spoilage? Will fuel be available such that a light always turns on whenever they flip the switch? Will adequate supplies of medicines always be available for the sick? Will the central authority be able to guarantee a range of good-quality clothing from which to choose?

There has never been a central authority that successfully performed the job just described. Yet that job gets done every day in free, capitalistic societies, and we tend to take it for granted. The massive process of information transmission and coordination takes place spontaneously with spectacularly good results via private discovery and decision-making, secure property rights, markets, and a functioning price mechanism. Individual economic units are endowed with decision-making power and the authority to manage their own relationships. And the spontaneous order that takes shape remains effective even as networks of economic units expand. In other words, markets are highly scalable at solving the eternal problem of allocating scarce resources.

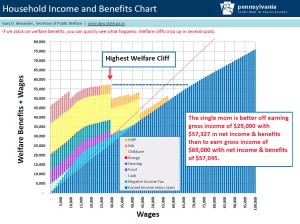

But thus far I’ve set up something of a straw man by presuming that the central authority must monitor all individual economic units to know and translate their demands and supplies of goods into the ongoing, myriad decisions about production, distribution and consumption. Suppose the central authority takes a less ambitious approach. For example, it might attempt to enforce a set of prices that its experts believe to be fair to both consumers and producers. This is a much simpler task of central management. What could go wrong?

These prices will be wrong immediately, to one degree or another, without tailoring them to detailed knowledge of the individual tastes, preferences, talents, productivities, price sensitivities, and resource endowments of individual economic units. It would be sheer luck to hit on the correct prices at the start, but even then they would not be correct for long. Conditions change continuously, and the new information is simply not available to the central authority. Various shortages and surpluses will appear without the corrective mechanism usually provided by markets. Queues will form here and inventories will accumulate there without any self-correcting mechanism. Consumers will be angry, producers will quit, goods will rot, and stocks of physical capital will sit idle and go to waste.

Other forms of planning attempt to set quantities of goods produced and are subject to errors similar to those arising from price controls. Even worse is an attempt to plan both price and quantity. Perhaps more subtle is the case of industrial policy, in which planners attempt to encourage the development of certain industries and discourage activity in those deemed “undesirable”. While often borne out of good intentions, these planners do not know enough about the future of technology, resource supplies, and consumer preferences to arrogate these kinds of decisions to themselves. They will invariably commit resources to inferior technologies, misjudge future conditions, and abridge the freedoms of those whose work or consumption is out-of-favor and those who are taxed to pay for the artificial incentives. To the extent that industrial policies become more pervasive, scalability will become an obstacle to the planners because they simply lack the information required to perform their jobs of steering investment wisely.

Here is Turner’s verdict on central planning:

“No central planner, or even a board of them, can accurately set prices across any nation larger than, maybe, Liechtenstein and quite likely even at the level of Liechtenstein it won’t work well. After all how can a central planner tell that Farmer X’s vegetables taste better and are less rotten than Farmer Y’s and that people therefore are prepared to pay more for a tomato from Farmer X than they are one from Farmer Y.”

I will go further than Turner: planning can only work well in small settings and only when the affected units do the planning. For example, the determination of contract terms between two parties requires planning, as does the coordination of activities within a firm. But then these plans are not really “central” and the planners are not “public”. These activities are actually parts of a larger market process. Otherwise, the paradigm of central planning is not merely unscalable, it is unworkable without negative consequences.

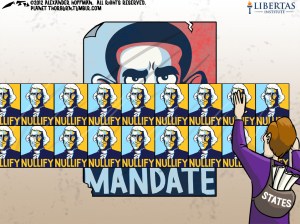

Finally, the notion of scalability applies broadly to governance, not merely economic planning. The following quote from Turner, for example, is a ringing endorsement for federalism:

“It is worth noting that almost all successful nations have different levels of government. You have the local town council, the state/province/county government, possibly a regional government and then finally the national one. Moreover richer countries tend to do better when they push more down to the lower levels. This is a classic way to solve a scalability problem – instead of having a single central power you devolve powers and responsibilities with some framework such that they follow the general desires of the higher levels of government but have freedom to implement their own solutions and adapt policies to local conditions.”