Tags

Ample Reserves, Basel III, Brian Wesbury, Capital Requirementd, Debt Monetization, Dodd-Frank, Fed Independence, Federal Reserve, Interbank Borrowing, Interest on Reserves, John Cochrane, Modern Monetary Theory, Nationalization, Nominal GDP Targeting, Operation Twist, Quantitative Easing, Reserve Requirements, Scarce Reserves, Scott Sumner, Socialized Risk

This topic flared up in 2025, with legislation proposing to end the Federal Reserve’s payment of interest on bank reserves (IOR). The bills have not yet advanced in Congress, however. As a preliminary on IOR and its broader implications, consider two hypotheticals:

First, imagine banks that take deposits, make loans, and invest in assets like government securities (i.e., Treasury debt). Banks are required to hold some percentage of reserves against their deposits at the central bank (the Fed), but the reserves earn nothing.

Now consider a world in which the Fed pays banks a risk-free interest rate on reserves. Banks will opt to hold plentiful reserves and relatively less in Treasuries. But in this scenario, the Fed itself holds large amounts of Treasuries and other securities, earns interest, and in turn pays interest to banks on their reserves.

The first scenario held sway in the U.S. until 2008, when Congress authorized the Fed to pay IOR. Since that time, we’ve had the second scenario: the IOR monetary order.

Socialized Risk

The central bank can basically print money, so there is no danger that banks won’t be paid IOR, despite some risk inherent in assets held by the Fed in its portfolio. While the rate paid on reserves can change, and banks are paid IOR every 14 days, they do not face the rate risk (and a modicum of default risk) inherent in holding Treasuries and mortgage securities, which have varying maturities. Instead, the Fed and ultimately taxpayers shoulder that risk, despite the Fed’s assurances that any portfolio losses and negative net interest income are economically irrelevant. These risks have been socialized, so we now share them.

This means that an essential function of the banking system, assessing and rationally pricing risks associated with certain assets, has been nationalized. It is a suspension of the market mechanism and an invitation to misallocated capital. Why bother to critically assess the risks inherent in assets if the Fed is happy to take them off your hands, possibly at a small premium, and then pay you a risk-free return on your cash to boot.

Bank Subsidies

IOR is a subsidy to banks. They get a return with zero risk, while taxpayers provide a funding bridge for any losses on the Fed’s holdings of securities on its balance sheet or any shortfall in the Fed’s net interest income. Banks, however, can’t lose money on their ample reserves.

The subsidy may come at a greater cost to some banks than others. This regime has been accompanied by significantly more regulation of bank balance sheets, such as capital and liquidity requirements (Basel III and Dodd-Frank). Not only is IOR a significant step toward nationalizing banks, but the attendant regulatory regime tends to favor large banks.

On the other hand, zero IOR with a positive reserve requirement amounts to a tax on banks, which is ultimately paid by bank customers. Allowing banks to hold zero reserves is out of the question, so we could view the implicit reserve-requirement tax as a cost of achieving some monetary stability and promoting safer depository institutions.

Quantitative Easing

Again, the advent of IOR created an incentive for banks to hold more reserves and relatively less in Treasuries and other assets (even some loans). Rather than “scarce reserves”, banks were encouraged by IOR to hold “ample reserves”. Of course, this is thought to promote stability and a safer banking system, but as Scott Sumner notes, it represents a contractionary policy owing to the increase in the demand for base money (reserves) by banks.

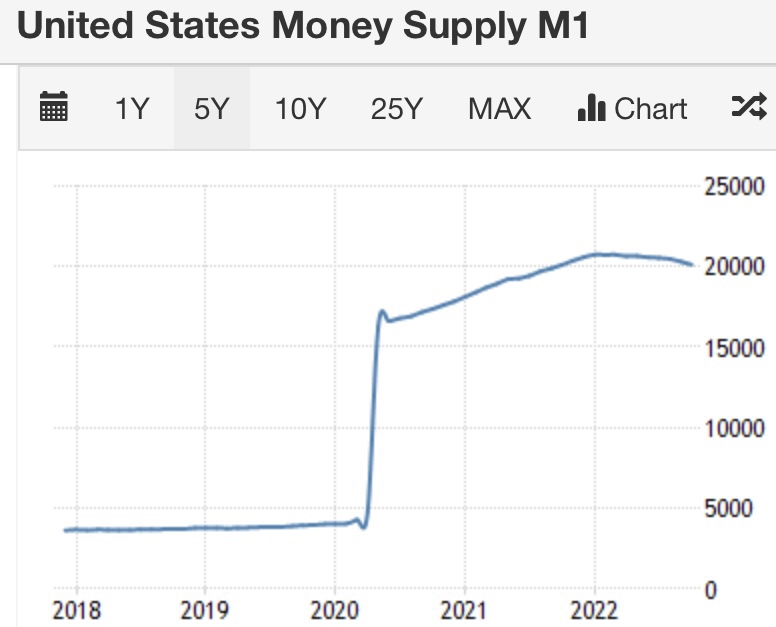

The Fed took up the slack in the debt markets, buying mortgage-backed securities and Treasuries for its own portfolio in large amounts. That kind of expansion in the Fed’s balance sheet is called quantitative easing (QE). which adds to the money supply as the Fed pays for the assets.

QE helped to neutralize the contractionary effect of IOR. And QE itself can be neutralized by other measures, including regulations governing bank capital and liquidity levels.

Fed Balance Sheet Policies

QE can’t go on forever… or can it? Perhaps no more than expanding federal deficits can go on forever! The Fed’s balance sheet topped out in 2022 at about $9 trillion. It stood at just over $6.5 trillion in November 2025.

Quantitative tightening (QT) occurs when the Fed sells assets or allows run-off in its portfolio as securities mature. Nevertheless, the Fed’s mere act of holding large amounts of debt securities (whether accompanied by QE, QT, or stasis) is essentially part of the ample reserves/IOR monetary regime: without it, the demand for debt securities would be undercut (because banks get a sweeter deal from the Fed, and so disintermediation occurs).

In terms of monetary stimulus, QE was more or less offset during the financial crisis leading into the Great Recession via higher demand for bank reserves (IOR) and stricter banking regulation. Higher capital requirements were justified as necessary to stabilize the financial system, but critics like Brian Wesbury stress that the real destabilizing culprit was mark-to-market valuation requirements.

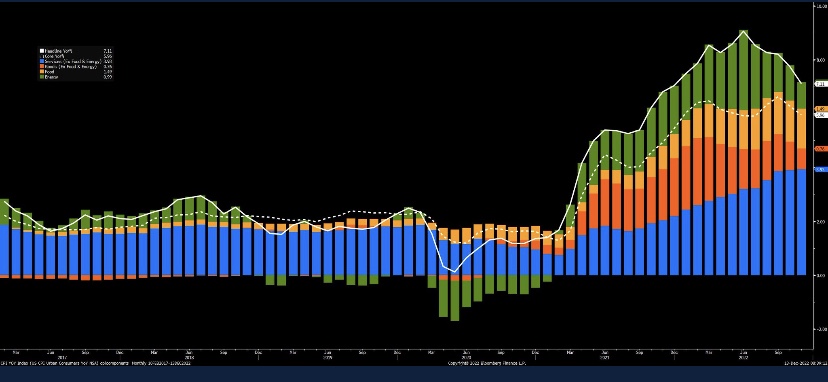

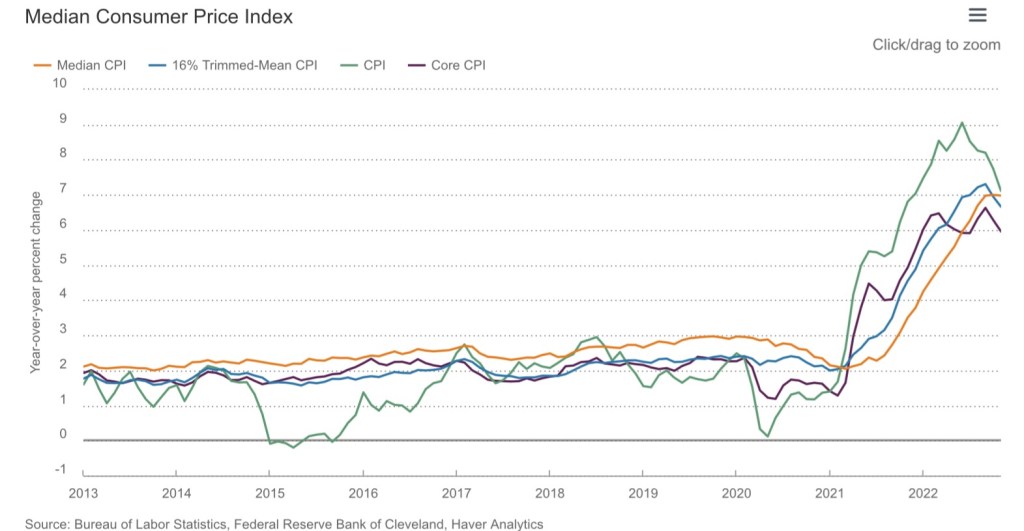

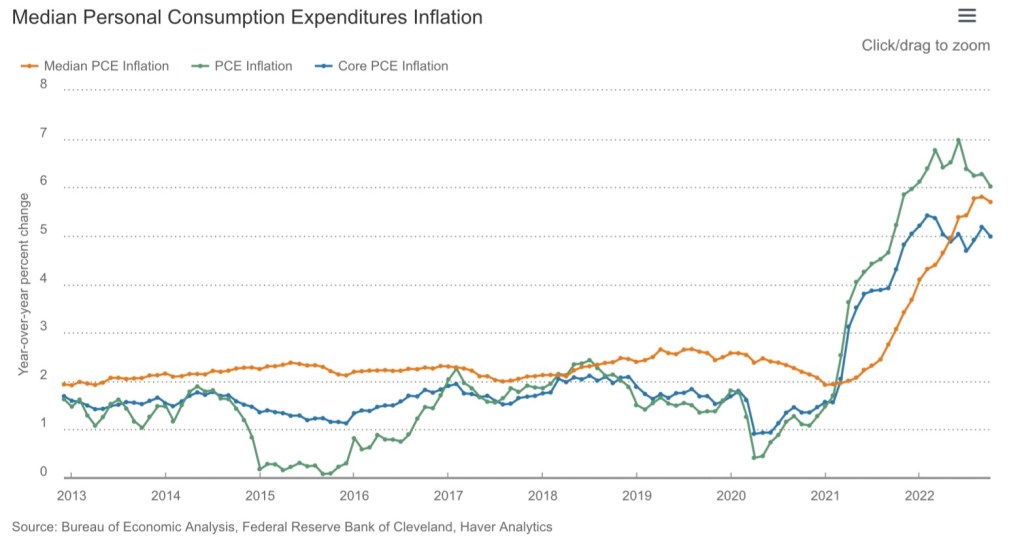

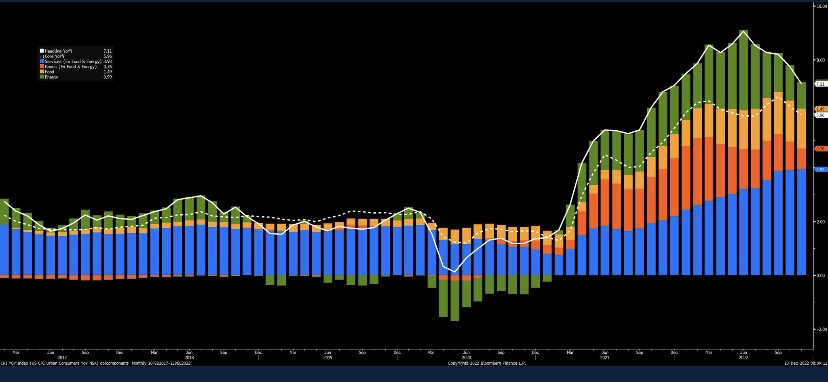

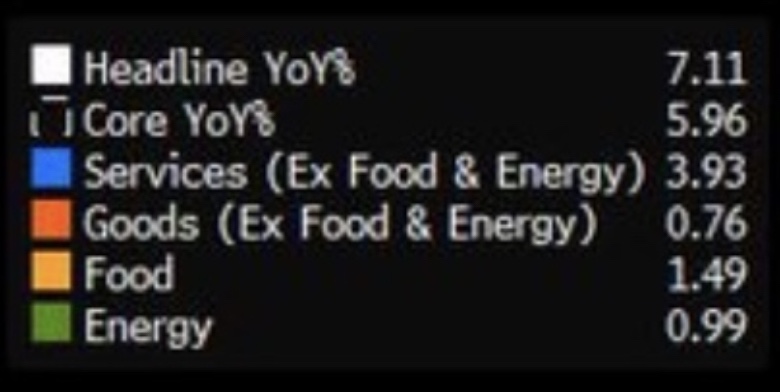

During the Covid pandemic, however, aggressive QE was intended to stabilize the economy and was not neutralized, so the Fed’s balance sheet and the money supply expanded dramatically. A surge in inflation followed.

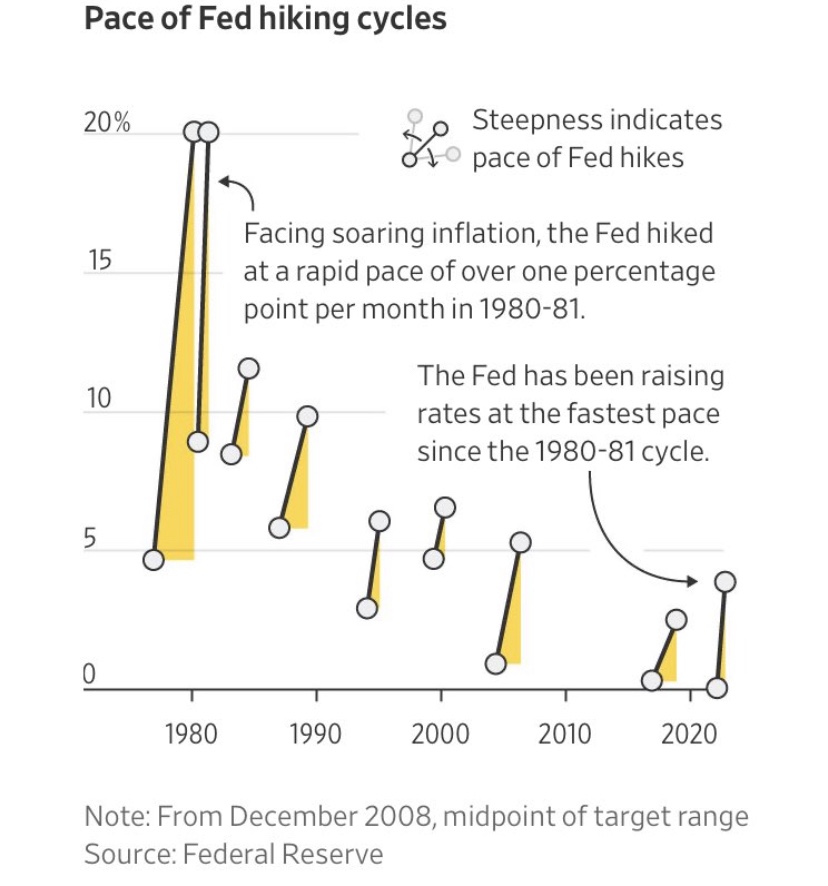

Rates and Monetary Policy

The IOR regime severs the connection between overnight rates and monetary policy, while artificially fixing the price of reserves. There is little interbank borrowing of reserves under this “ample reserves” policy. But if there is little or no volume, what’s the true level of the Fed funds rate? Some critics (like Wesbury) claim it’s basically made up by the Fed! In any case, there is no longer any real connection between the fed funds rate and the tenor of monetary policy.

Instead, the rate paid to banks on reserves essentially sets a floor on short-term interest rates. And whenever the Fed seeks to tighten policy via IOR rate actions, it faces a potential loss on its interest spread. That represents a conflict of interest for Fed policymaking.

Sumner dislikes the IOR arrangement because, he say, it reinforces the false notion that interest rates are key to understanding monetary policy. For example, higher short-term rates are not always consistent with lower inflation. Sumner prefers controlling the monetary base as a means of targeting the level of nominal GDP, allowing interest rates to signal reserve scarcity. All of that is out of the question as long as the Fed is manipulating the IOR rate.

The Fed As Treasury Lapdog

With IOR and ample reserves, the Fed’s management of a huge portfolio of securities puts it right in the middle of the debt market across a range of maturities. As implied above, that distorts pricing and creates tension between fiscal policy and “independent” monetary policy. Such tension is especially troubling given ongoing, massive federal deficits and increasing Administration pressure on the Fed to reduce rates.

Of course, when the Fed engages in QE, or actively turns over and replaces its holdings of maturing Treasuries with new ones, it is monetizing deficits and creating inflationary pressure. It’s one kind of money printing, the mechanism by which an inflation tax is traditionally understood to reduce the real value of federal debt.

The IOR monetary regime is not the first time the Fed has intervened in the debt markets at longer maturities. In 1961, the Fed ran “Operation Twist”, selling short-term Treasuries and buying long-term Treasuries in an effort to reduce long-term rates and stimulate economic activity. However, the operation did not result in an increase in the Fed’s balance sheet holdings and cannot be interpreted as debt monetization.

Fed Adventurism

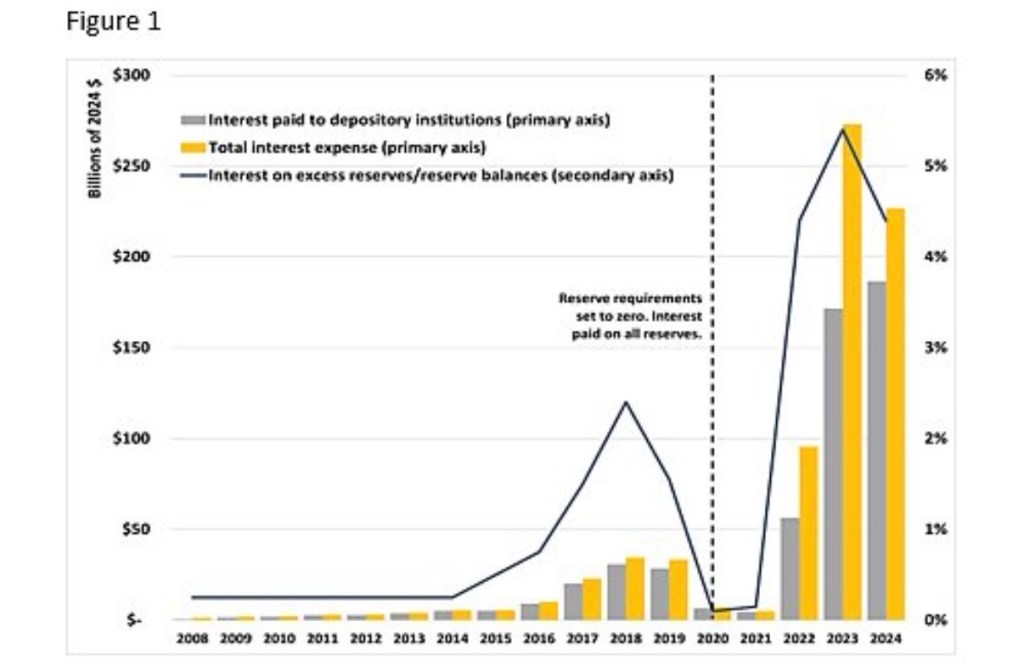

The Fed earned positive net interest income from 2008-2023, enabling it to turn over profits to the Treasury. This had a negative effect on federal deficits. However, some contend that the Fed’s net interest income over those years fostered mission creep. Wesbury notes that the Fed dabbled in “… research on climate change, lead water pipes and all kinds of other issues like ‘inequality’ and ‘racism.’” These topics are far afield of the essential functions of a central bank, monetary authority, or bank regulator. One can hope that keeping the Fed on a tight budgetary leash by ending the IOR monetary regime would limit this kind of adventurism.

A Contrary View

John Cochrane insists that IOR is a “lovely innovation”. In fact, he wonders whether the opposition to IOR is grounded in nostalgic, Trumpian hankering for zero interest rates. Cochrane also asserts that IOR is “usually” costless because longer-term rates on the Fed’s portfolio tend to exceed the short-term rate earned on reserves. That’s not true at the moment, of course, and the value of securities in the Fed’s portfolio tanked when interest rates rose. The Fed treats the shortfall in net interest as an increment to a “deferred asset”, but the negative profit, in the interim, must be met by taxpayers (who would normally benefit from the Fed’s profit) or printing money. The Fed shoulders ongoing interest-rate risk, freeing banks of the same to the extent that they hold reserves. Again, this subsidy has a real cost.

I’m surprised that Cochrane doesn’t see the strong potential for monetary lapdoggery under the IOR regime. Sure, the Fed can always print money and load up on new issues of Treasury debt. But IOR and an ongoing “quantitative” portfolio create an institutional bias toward supporting fiscal incontinence.

I’m also surprised that Cochrane would characterize an attempt to end IOR as easier monetary policy. Such a change would be accompanied by an unwinding of the Fed’s mammoth portfolio (QT). That might or might not mean tighter policy, on balance. Such an unwinding would be neutralized by lower demand for bank reserves and a lighter regulatory touch, and it should probably be phased in over several years.

Conclusion

Norbert Michel summarizes the problems created by IOR (the chart at the top of this post is from Michel). Here is a series of bullet points from his December testimony before the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee (no quote marks below, as I paraphrase his elaborations):

- The economic cost of the Fed’s losses is high. Periodic or even systemic failures to turn profits over to the Treasury means more debt, taxes, or inflation.

- The IOR framework creates a conflict of interest with the Fed’s mandate to stabilize prices. The IOR rate set by the Fed has an impact on its profitability, which can be inconsistent with sound monetary policy actions.

- The IOR system facilitates government support for the private financial sector. Banks get a risk-free return and the Fed acquiesces to bearing rate risk.

- More accessible money spigot. The Fed can buy and hold Treasury debt, helping to fund burgeoning deficits, while paying banks to hold the extra cash that creates.

The money spigot enables wasteful expansion of government. Unfortunately, far too many partisans are under the delusion that more government is the solution to every problem, rather than the root cause of so much dysfunction. And of course advocates of so-called Modern Monetary Theory are all for printing the money needed to bring about the “warmth of collectivism”.