Tags

adverse selection, Affordable Care Act, Arnold Kling, Bryan Caplan, Claim Denials, David Chavous, Donald Trump, Employer-Provided Coverage, Essential Benefits, Hospital Readmissions, Joel Zinberg, Liam Sigaud, Make America Healthy Again, Matt Margolis, Michael F. Cannon, Moral Hazard, Noah Smith, Obamacare, Peter Earle, Pharmacy Benefit Managers, Portability, Pre-Authorization Rules, Pre-Existing Conditions, Premium Subsidies, Robert F. Kennedy Jr, Sebastian Caliri, Steven Hayward, Tax-Deductible Premiums, third-party payments, Universal Health Accounts

Ongoing increases in the resources dedicated to health care in the U.S., and their prices, are driven primarily by the abandonment of market forces. We have largely eliminated the incentives that markets create for all buyers and sellers of health care services as well as insurers. Consumers bear little responsibility for the cost of health care decisions when third parties like insurers and government are the payers. A range of government interventions have pushed health care spending upward, including regulation of insurers, consumer subsidies, perverse incentives for consolidation among health care providers, and a mechanism by which pharmaceutical companies negotiate side payments to insurers willing to cover their drugs.

It’s not yet clear whether the Trump Administration and its “Make America Healthy Again” agenda will serve to liberate market forces in any way. Skeptics can be forgiven for worrying that MAHA will be no more than a cover for even more centrally-planned health care, price controls, and regulation of the pharmaceutical and food industries, not to mention consumer choices. Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who is likely to be confirmed by the Senate as Donald Trump’s Secretary of Health and Human Services, has strong and sometimes defensible opinions about nutrition and public health policies. He is, however, an inveterate left-winger and is not an advocate for market solutions. Trump himself has offered only vague assurances on the order of “You won’t lose your coverage”.

Government Control

The updraft in health care inflation coincided with government dominance of the sector. Steven Hayward points out that the cost pressure began at about the same time as Medicare came into existence in 1965. This significantly pre-dates the trend toward aging of the population, which will surely exacerbate cost pressures as greater concentrations of baby boomers approach or exceed life expectancy over the next decade.

Government now controls or impinges on about 84% of health care spending in the U.S., as noted by Michael F. Cannon. The tax deductibility of employer-provided health insurance is a massive example of federal manipulation and one that is highly distortionary. It reinforces the prevalence of third-party payments, which takes decision-making out of consumers’ hands. Equalizing the tax treatment of employer-provided health coverage would obviously promote tax equity. Just as importantly, however, tax-subsidized premiums create demand for inflated coverage levels, which raise prices and quantities. And today, the federal government requires coverages for routine care, going beyond the basic function of insurance and driving the cost of care and insurance upward.

The traditional non-portability of employer-provided coverage causes workers with uninsurable pre-existing conditions to lose coverage when they leave a job. Thus, Cannon states that the tax exclusion for employer coverage penalizes workers who instead might have chosen portable individual coverage in a market setting without tax distortions. Cannon proposes a reform whereby employer coverage would be replaced with deposits into tax-free Universal Health Accounts owned by workers, who could then purchase their own insurance.

In 2024, federal subsidies for health insurance coverage were about $2 trillion, according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Those subsidies are projected to grow to $3.5 trillion by 2034 (8.5% of GDP). Joel Zinberg and Liam Sigaud emphasize the wasteful nature of premium subsidies for exchange plans mandated by the Affordable Care Act (ACA), better known as Obamacare. Subsidies were temporarily expanded in 2021, but only until 2026. They should be allowed to expire. These subsidies increase the demand for health care, but they are costly to taxpayers and are offered to individuals far above the poverty line. Furthermore, as Zinberg and Sigaud discuss, subsidized coverage for the previously uninsured does very little to improve health outcomes. That’s because almost all of the health care needs of the formerly uninsured were met via uncompensated care at emergency rooms, clinics, medical schools, and physician offices.

Proportionate Consumption

Perhaps surprisingly, and contrary to popular narratives, health care spending in the U.S. is not really out-of-line with other developed countries relative to personal income and consumption expenditures (as opposed to GDP). We spend more on health care because we earn and consume more of everything. This shouldn’t allay concern over health care spending because our economic success has not been matched by health outcomes, which have lagged or deteriorated relative to peer nations. Better health might well have allowed us to spend proportionately less on health care, but this has not been the case. There are explanations based on obesity levels and diet, but important parts of the explanation can be found elsewhere.

It should also be noted that a significant share of our decades-long increases in health care spending can be attributed to quantities, not just prices, as explained at the last link above.

Health Consequences

The ACA did nothing to slow the rise in the cost of health care coverage. In fact, if anything, the ACA cemented government dominance in a variety of ways, reinforcing tendencies for cost escalation. Even worse, the ACA had negative consequences for patient care. David Chavous posted a good X thread in December on some of the health consequences of Obamacare:

1) The ACA imposed penalties on certain hospital readmissions, which literally abandoned people at death’s door.

2) It encouraged consolidation among providers in an attempt to streamline care and reduce prices. This reduced competitive pressures, however, which had the “unforeseen” consequence of raising prices and discouraging second opinions. The former goes against all economic logic while the latter goes against sound medical decision-making.

3) The ACA forced insurers to offer fewer options, increasing the cost of insurance by encouraging patients to wait until they had a pre-existing condition to buy coverage. Care was almost certainly deferred as well. Ultimately, that drove up premiums for healthy people and worsened outcomes for those falling ill.

4) It forced drug companies to negotiate with Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) to get their products into formularies. The PBMs have acted as classic middlemen, accomplishing little more than driving up drug prices and too often forcing patients to skimp on their prescribed dosage, or worse yet, increasing their vulnerability to lower-priced quackery.

The Insurers

So the ACA drastically increased the insured population (including the new burden of covering pre-existing conditions). It also forced insurers to meet draconian cost-control thresholds. Little wonder that claim rejection increased, a phenomenon often at the root of public animosity toward health insurers. Peter Earle cites several reasons for the increase in denial rates while noting that claim rejection has made little difference in insurer profit margins.

Matt Margolis points out that under the ACA, we’ve managed to worsen coverage in exchange for higher premiums and deductibles. All while profits have been capped. Claim denials or delays due to pre-authorization rules (which delay care) have become routine following the implementation of Obamacare.

Perhaps the biggest mistake was forcing insurers to cover pre-existing conditions without allowing them to price for risk. Rather than forcing healthy individuals to pay for risks they don’t face, it would be more economically sensible to directly subsidize coverage for those in high-risk pools.

Noah Smith also defends the health insurers. For example, while UnitedHealth Group has the largest market share in the industry, its net profit margin of 6.1% is only about half of the average for the S&P 500. Other major insurers earn even less by this metric. Profits just don’t explain why American health care spending is so high. Ultimately, the services delivered and charges assessed by providers explain high U.S. health care spending, not insurer profits or administrative costs.

Under the ACA, insurance premiums pay the bulk of the cost of health care delivery, including the cost of services more reasonably categorized as routine health maintenance. The latter is like buying insurance for oil changes. Furthermore, there are no options to decline any of the ten so-called “essential benefits” under the ACA, thus increasing the cost of coverage.

Medical Records

Arnold Kling argues that the ACA’s emphasis on uniform, digitized medical records is not a productive avenue for achieving efficiencies in health care delivery. Moreover, it’s been a key factor driving the increasing concentration in the health care industry. Here is Kling:

“My point is that you cannot do this until you tighten up the health care delivery process, making it more rigid and uniform. And I would not try to do that. Health care does not necessarily lend itself to being commoditized. You risk making health care in America less open to innovation and less responsive to the needs of people.

“So far, all that has been accomplished by the electronic medical records drive has been to put small physician practices out of business. They have not been able to absorb the overhead involved in implementing these systems, so that they have been forced to lose their independence, primarily to hospital-owned conglomerates.”

Separating Health and State

The problem of rising health care costs in the U.S. is capsulized by Bryan Caplan in his call for the separation of health and state. The many policy-driven failures discussed above offer more than adequate rationale for reform. The alternative suggested by Caplan is to “pull the plug” on government involvement in health care, relying instead on the free market.

Caplan debunks a few popular notions regarding the appropriate role for markets in health care and health insurance. In particular, it’s often alleged that moral hazard and adverse selection would encourage unhealthy behaviors and encourage the worst risks to over-insure, causing insurance markets to fail. But these problems arise only when risk is not priced efficiently, precisely what the government has accomplished by attempting to equalizing rates.

Pulling the plug on government interference in health care would also mean deregulating both insurance offerings and pricing, encouraging the adoption of portable coverage, expediting drug approvals based on peer-country approvals, reforming pharmacy benefit management, ending deadly Medicare drug price controls, and encouraging competition among health care providers.

Value Vs. Volume

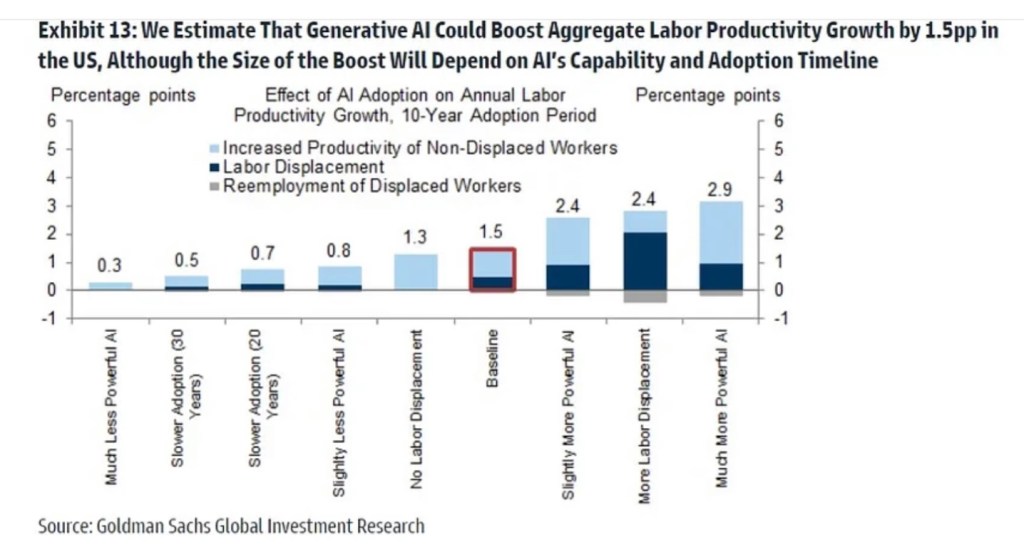

There are a host of other reforms that could bring more sanity to our health care system. Many of these are covered here by Sebastian Caliri, with some emphasis on the potential role of AI in improving health care. Some of these are at odds with Kling’s skepticism regarding digitized health records.

Perhaps the most fundamental reforms entertained by Caliri have to do with health care payments. One is to make payments dependent on outcomes rather than diagnostic codes established and priced by the American Medical Association. To paraphrase Caliri, it would be far better for Americans to pay for value rather than volume.

Another payment reform discussed by Caliri is expanding direct payments to providers such as capitation fees, whereby patients pay to subscribe to a bundle of services for a fixed fee. Finally, Caliri discusses the importance of achieving “site-neutral payments”, eliminating rules that allow health systems to charge a higher premium relative to independent providers for identical services.

For what it’s worth, Arnold Kling disagrees that changing payment metrics would be of much help because participants will learn to game a new system. Instead, he emphasizes the importance of reducing consumer incentives for costly treatments having little benefit. No dispute there!

Avoid the Single-Payer Calamity

I’ll close this jeremiad with a quote from Caliri’s piece in which he contrasts the knee-jerk, leftist solution to our nation’s health care dilemma with a more rational, market-oriented approach:

“Single payer solutions and government control favored by the left are no solutions at all. Moving to a monopsonist system like Canada is a recipe for strangling innovation and rationing access. Just ask our neighbors to the north who have to wait a year for orthopedic surgery. The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) is teetering on the brink of collapse. We need to sort out some other way forward.

“Other parts of the economy provide inspiration for what may actually work. In the realm of information technology, for example, fifty years has taken us from expensive four operation calculators to ubiquitous, free, artificial intelligence capable of passing the Turing Test. We can argue about the precise details but most of this miracle came from profit-seeking enterprises competing in a free market to deliver the best value for the buyer’s dollar.“