I’ve long been suspicious of the objectivity of Google search results. If you’re looking for information on a particular issue or candidate for public office, it doesn’t take long to realize that Google searches lean left of center. To some extent, the bias reflects the leftward skew of the news media in general. If you sample material available online from major news organizations on any topic with a political dimension, you’ll get more left than right, and you’ll get very little libertarian. So it’s not just Google. Bing reflects a similar bias. Of course, one learns to craft searches to get the other side of a story, but I use Bing much more than Google, partly because I bridle instinctively at Google’s dominance as a search engine. I’ve also had DuckDuckGo bookmarked for a long time. Lately, my desire to avoid tracking of personal information and searches has made DuckDuckGo more appealing.

Google is not just a large company offering internet services and an operating system: it has the power to control speech and who gets to speak. It is a provider of information services and a collector of information with the power to exert geopolitical influence, and it does. This is brought into sharp relief by Julian Assange in his account of an interview he granted in 2011 to Google’s chairman Eric Schmidt and two of Schmidt’s advisors, and by Assange’s subsequent observations about the global activities of these individuals and Google. Assange gives the strong impression that Google is an arm of the deep state, or perhaps that it engages in a form of unaccountable statecraft, one meant to transcend traditional boundaries of sovereignty. Frankly, I found Assange’s narrative somewhat disturbing.

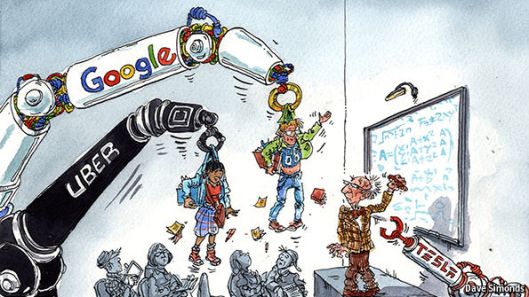

Monopolization

These concerns are heightened by Google’s market dominance. There is no doubt that Google has the power to control speech, surveil individuals with increasing sophistication, and accumulate troves of personal data. Much the same can be said of Facebook. Certainly users are drawn to the compelling value propositions offered by these firms. The FCC calls them internet “edge providers”, not the traditional meaning of “edge”, as between interconnected internet service providers (ISPs) with different customers. But Google and Facebook are really content providers and, in significant ways, hosting services.

According to Scott Cleland, Google, Facebook, and Amazon collect the bulk of all advertising revenue on the internet. The business is highly concentrated by traditional measures and becoming more concentrated as it grows. In the second quarter of 2017, Google and Facebook controlled 96% of digital advertising growth. They have ownership interests in many of the largest firms that could conceivably offer competition, and they have acquired outright a large number of potential competitors. Cleland asserts that the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the FTC essentially turned a blind eye to the many acquisitions of nascent competitors by these firms.

The competitive environment has also been influenced by other government actions over the past few years. In particular, the FCC’s net neutrality order in 2015 essentially granted subsidies to “edge providers”, preventing broadband ISPs (so-called “common carriers” under the ruling) from charging differential rates for the high volume of traffic they generate. In addition, the agency ruled that ISPs would be subject to additional privacy restrictions:

“Specifically, broadband Internet providers were prohibited from collecting and using information about a consumer’s browsing history, app usage, or geolocation data without permission—all of which edge providers such as Google or Facebook are free to collect under FTC policies.

As Michael Horney noted in an earlier Free State Foundation Perspectives release, these restrictions create barriers for ISPs to compete in digital advertising markets. With access to consumer information, companies can provide more targeted advertising, ads that are more likely to be relevant to the consumer and therefore more valuable to the advertiser. The opt-in requirement means that ISPs will have access to less information about customers than Google, Facebook, and other edge providers that fall under the FTC’s purview—meaning ISPs cannot serve advertisers as effectively as the edge providers with whom they compete.”

Furthermore, there are allegations that Google played a role in convincing Facebook to drop Bing searches on its platform, and that Google in turn quietly deemphasized its social media presence. There is no definitive evidence that Google and Facebook have colluded, but the record is curious.

Regulation and Antitrust

Should firms like Google, Facebook, and other large internet platforms be regulated or subjected to more stringent review of past and proposed acquisitions? These companies already have great influence on the public sector. The regulatory solution is often comfortable for the regulated firm, which submits to complex rules with which compliance is difficult for smaller competitors. Thus, the regulated firm wins a more secure market position and a less risky flow of profit. The firm also gains more public sector influence through its frequent dealings with regulatory authorities.

Ryan Bourne argues that “There Is No Justification for Regulating Online Giants as If They Were Public Utilities“. He notes that these firms are not natural monopolies, despite their market positions and the existence of strong network externalities. It is true that they generally operate in contested markets, despite the dominance of a just few firms. Furthermore, it would be difficult to argue that these companies over-charge for their services in any way suggestive of monopoly behavior. Most of their online services are free or very cheap to users.

But anti-competitive behavior can be subtle. There are numerous ways it can manifest against consumers, developers, advertisers, and even political philosophies and those who espouse them. In fact, the edge providers do manage to extract something of value: data, intelligence and control. As mentioned earlier, their many acquisitions suggest an attempt to snuff out potential competition. More stringent review of proposed combinations and their competitive impact is a course of action that Cleland and others advocate. While I generally support a free market in corporate control, many of Google’s acquisitions were firms enjoying growth rates one could hardly attribute to mismanagement or any failure to maximize value. Those combinations expanded Google’s offerings, certainly, but they also took out potential competition. However, there is no bright line to indicate when combinations of this kind are not in the public interest.

Antitrust action is no stranger to Google: In June, the European Union fined the company $2.7 billion for allegedly steering online shoppers toward its own shopping platform. Google faces continuing scrutiny of its search results by the EU, and the EU has other investigations of anticompetitive behavior underway against both Google and Facebook.

It’s also worth noting that antitrust has significant downsides: it is costly and disruptive, not only for the firms involved, but for their customers and taxpayers. Alan Reynolds has a cautionary take on the prospect of antitrust action against Amazon. Antitrust is a big business in and of itself, offering tremendous rent-seeking benefits to a host of attorneys, economists, accountants and variety of other technical specialists. As Reynolds says:

“Politics aside, the question ‘Is Amazon getting too Big?’ should have nothing to do with antitrust, which is supposedly about preventing monopolies from charging high prices. Surely no sane person would dare accuse Amazon of monopoly or high prices.“

Meanwhile, the proposed Amazon-Whole Foods combination was approved by the FTC and the deal closed Monday.

Speech, Again

Ordinarily, my views on “speech control” would be aligned with those of Scott Shackford, who defends the right of private companies to restrict speech that occurs on their platforms. But Alex Tabbarok offers a thoughtful qualification in asking whether Google and Apple should have banned Gab:

“I have no problem with Twitter or Facebook policing their sites for content they find objectionable, such as pornography or hate speech, even though these are permitted under the First Amendment. A free market in news doesn’t mean that every newspaper must cover every story. A free market in news means free entry. But free entry is exactly what is now at stake. Gab was created, in part, to combat what was seen as Facebook’s bias against conservative news and views. If Gab or services like cannot be accessed via the big platforms that is a significant barrier to entry.

When Facebook and Twitter regulate what can be said on their platforms and Google and Apple regulate who can provide a platform, we have a big problem. It’s as if the NYTimes and the Washington Post were the only major newspapers and the government regulated who could own a printing press.

In a pure libertarian world, I’d be inclined to say that Google and Apple can also police whom they allow on their platforms. But we live in a world in which Google and Apple are bound up with and in some ways beholden to the government. I worry when a lot of news travels through a handful of choke points.“

This point is amplified by Aaron M. Renn in City Journal:

“The mobile-Internet business is built on spectrum licenses granted by the federal government. Given the monopoly power that Apple and Google possess in the mobile sphere as corporate gatekeepers, First Amendment freedoms face serious challenges in the current environment. Perhaps it is time that spectrum licenses to mobile-phone companies be conditioned on their recipients providing freedoms for customers to use the apps of their choice.“

That sort of condition requires ongoing monitoring and enforcement, but the intervention is unlikely to stop there. Once the platforms are treated as common property there will be additional pressure to treat their owners as public stewards, answerable to regulators on a variety of issues in exchange for a de facto grant of monopoly.

Tyler Cowen’s reaction to the issue of private, “voluntary censorship” online is a resounding “meh”. While he makes certain qualifications, he does not believe it’s a significant issue. His perspective is worth considering:

“It remains the case that the most significant voluntary censorship issues occur every day in mainstream non-internet society, including what gets on TV, which books are promoted by major publishers, who can rent out the best physical venues, and what gets taught at Harvard or for that matter in high school.“

Cowen recognizes the potential for censorship to become a serious problem, particularly with respect to so-called “chokepoint” services like Cloudflare:

“They can in essence kick you off the entire internet through a single human decision not to offer the right services. …so far all they have done is kick off one Nazi group. Still, I think we should reexamine the overall architecture of the internet with this kind of censorship power in mind as a potential problem. And note this: the main problem with those choke points probably has more to do with national security and the ease of wrecking social coordination, not censorship. Still, this whole issue should receive much more attention and I certainly would consider serious changes to the status quo.“

There are no easy answers.

Conclusions

The so-called edge providers pose certain threats to individuals, both as internet users and as free citizens: the potential for anti-competitive behavior, eventually manifesting in higher prices and restricted choice; tightening reins on speech and free expression; and compromised privacy. All three have been a reality to one extent or another. As a firm like Google attains the status of an arm of the state, or multiple states, it could provide a mechanism whereby those authorities could manipulate behavior and coerce their citizens, making the internet into a tool of tyranny rather than liberty. “Don’t be evil” is not much of a guarantee.

What can be done? The FCC’s has already voted to reverse its net neutrality order, and that is a big step; dismantling the one-sided rules surrounding the ISPs handling of consumer data would also help, freeing some powerful firms that might be able to compete for “edge” business. I am skeptical that regulation of edge providers is an effective or wise solution, as it would not achieve competitive outcomes and it would rely on the competence and motives of government officials to protect users from the aforementioned threats to their personal sovereignty. Antitrust action may be appropriate when anti-competitive actions can be proven, but it is a rent-seeking enterprise of its own, and it is often a questionable remedy to the ills caused by market concentration. We have a more intractable problem if access cannot be obtained for particular content otherwise protected by the First Amendment. Essentially, Cowen’s suggestion is to rethink the internet, which might be the best advice for now.

Ultimately, active consumer sovereignty is the best solution to the dominance of firms like Google and Facebook. There are other search engines and there are other online communities. Users must take steps to protect their privacy online. If they value their privacy, they should seek out and utilize competitive services that protect it. Finally, perhaps consumers should consider a recalibration of their economic and social practices. They may find surprising benefits from reducing their dependence on internet services, instead availing themselves of the variety of shopping and social experiences that still exist in the physical world around us. That’s the ultimate competition to the content offered by edge providers.