Tags

Al Gore, Barack Obama, Bernie Sanders, Bill Clinton, Border Security, Chuck Schumer, DEI, Department of Education, Department of Government Efficiency, Department of Interior, Discretionary Budget, DOGE, Donald Trump, Elon Musk, entitlements, FDA, Force Reductions, Fourth Branch, Fraud, Graft, HHS, Indirect Costs, Jimmy Carter, Joe Biden, Mandatory Budget, Medicaid, Medicare, Nancy Pelosi, NIH Grants, Obamacare, Provisional Employees, Public debt, Severance Packages, Social Security, U.S. Digital Service, U.S. Postal Service, USAID, Voluntary Separations, Waste

I prefer a government that is limited in size and scope, sticking closely to the provision of public goods without interfering in private markets. Therefore, I’m delighted with the mission of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), a rebranded version of the U.S. Digital Service created by Barack Obama in 2014 to clean up technical issues then plaguing the Obamacare web site. The “new” DOGE is fanning out across federal agencies to upgrade systems and eliminate waste and fraud.

A Strawman

For years, democrats such as Barack Obama and Joe Biden have advocated for eliminating waste in government. So did Bill Clinton, Al Gore, Bernie Sanders, Chuck Schumer, and Nancy Pelosi. Here’s Mark Cuban on the same point. Were these exhortations made in earnest? Or were they just lip service? Now that a real effort is underway to get it done, we’re told that only fascists would do such a thing.

I’m seeing scary posts about DOGE even on LinkedIn, such as the plight of Americans unable to get federal public health communications due to layoffs at HHS, while failing to mention the thousands of new HHS employees hired by Biden in recent years. As if HHS was particularly effective in dispensing good public health advice during the pandemic!

Those kinds of assertions are hard to take seriously. For reasons like these and still others, I tend to dismiss nearly all of the horror stories I hear about DOGE’s activities as nitwitted virtue signals or propaganda.

Many on the left claim that DOGE’s work is careless, and especially the force reductions they’ve spearheaded. For example, they claim that DOGE has failed to identify key employees critical to the functioning of the bureaucracy. The tone of this argument is that “this would not pass muster at a well-managed business”. A “sober” effort to achieve efficiencies within the federal bureaucracy, the argument goes, would involve much more consideration. In other words, given political realities, it would not get done, and they really don’t want it to get done.

The best rationale for the ostensible position of these critics might be situations like the dismissal of several thousand provisional employees at the FDA, a few of whom were later rehired to help manage the work load of reviewing and approving drugs. However, thus far, only a tiny percentage of the federal force reductions under consideration have involved immediate layoffs.

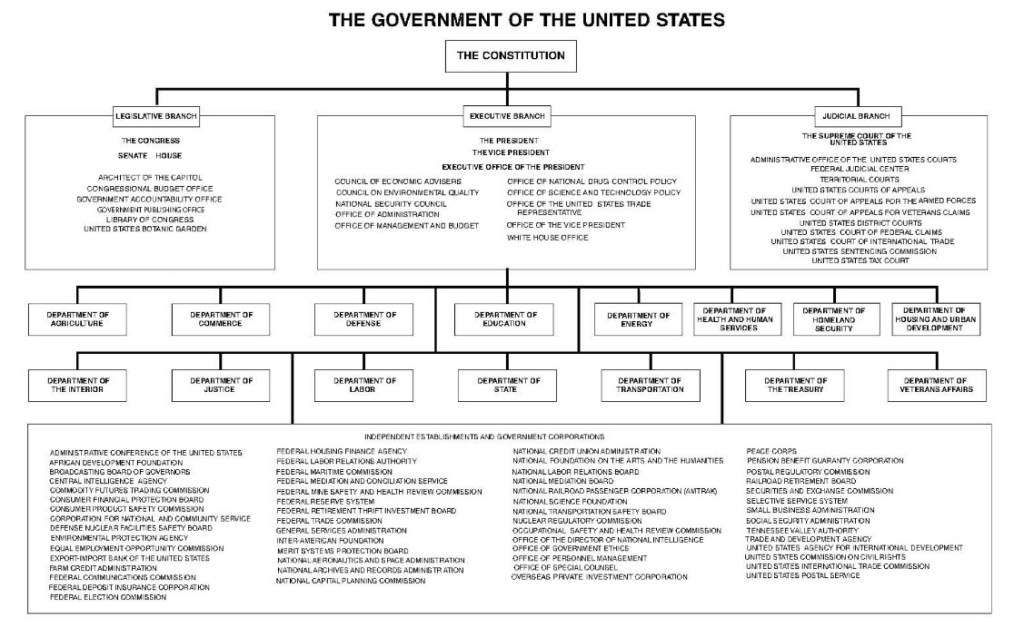

Of course, DOGE is not being tasked to review the practices of a well-managed business or a well-managed governmental organization. What we have here is a dysfunctional government. It is a bloated, low productivity Leviathan run by management and staff who, all too frequently, seem oblivious to the predicament. Large force reductions at all levels are probably necessary to make headway against entrenched interests that have operated as a fourth branch of government.

Thus, I see the leftist critique of Trump’s force reductions as something of a strawman, and it falls flat for several other reasons. First, the vast bulk of the prospective reduction in headcount will be voluntary, as the separating employees have been offered attractive severance packages. Second, force reductions in the private sector always feel chaotic, and they often are. And they are sometimes executed without regard to the qualifications of specific employees. Tough luck!

Duplicative functions, poor data systems, and a lack of control have led to massive misappropriations of funds. The dysfunction has been enabled by a metastasization of nests of administrative authority inside agencies with “incomprehensible” org charts, often having multiple departments with identical functions that do not communicate. These departments frequently use redundant but unconnected systems. A related problem is the inadequacy of documentation for outgoing payments. Needless to say, this is a hostile environment for effective spending controls.

It’s worth emphasizing, by the way, DOGE’s “open book” transparency. It’s not as if Elon Musk and DOGE are attempting to sabotage the deep state in the dark of night. Indeed, they are shouting from the rooftops!

Doing It Fast

Every day we have a new revelation from DOGE of incredible waste in the federal bureaucracy. Check out this story about a VA contact for web site maintenance. All too ironically, what we call government waste tends to have powerful, self-interested, and deeply corrupt constituencies. This makes speed an imperative for DOGE. In a highly politicized and litigious environment, the extent to which the Leviathan can be brought to heel is partly a function of how quickly the deconstruction takes place. One must pardon a few temporary dislocations that otherwise might be avoided in a world free of rent seeking behavior. Otherwise, the graft (no, NOT “grift”) will continue unabated.

The foregoing offers sufficient rationale not only for speedy force reductions, but also for system upgrades, dissolution of certain offices, and consolidation of core functions under single-agency umbrellas.

The Bloody Budget

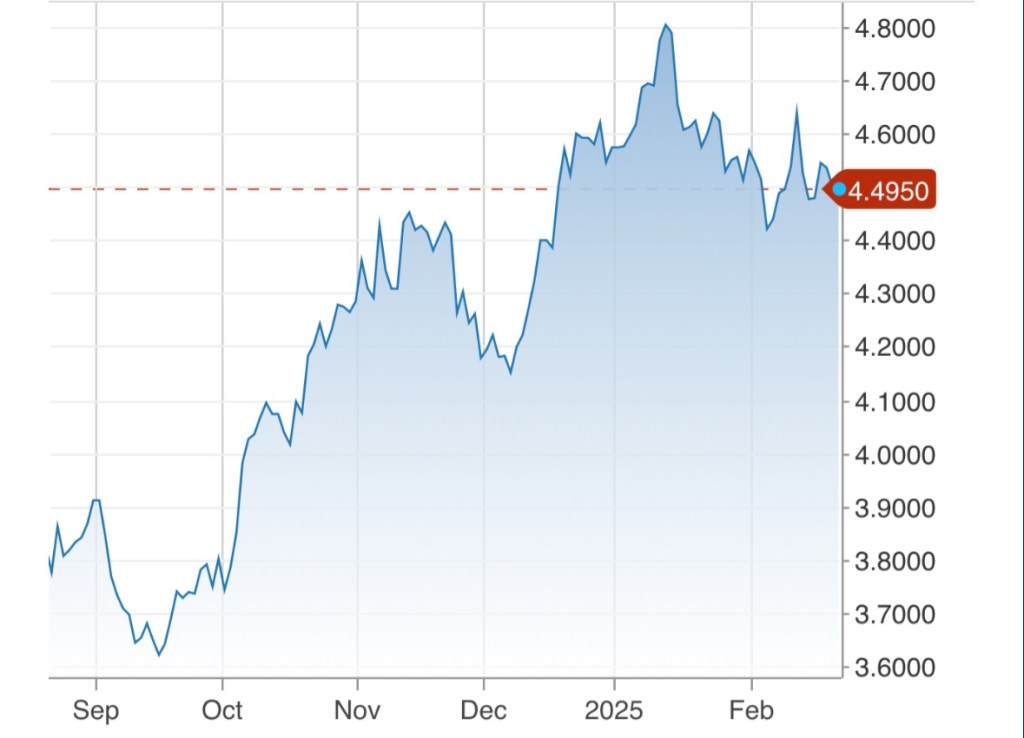

It’s difficult to know when budget legislation will begin to reflect DOGE’s successes. The actual budget deficit might be affected in fiscal year 2025, but so far the savings touted by DOGE are chump change compared to the expected $2 trillion deficit, and only a fraction of those savings contribute to ongoing deficit reduction.

Uncontrolled spending is the root cause of the deficit, as opposed to insufficient tax revenue, as evidenced by a relatively stable ratio of taxes to GDP. The spending problem was exacerbated by the pandemic, but Congress and the Biden Administration never managed to scale outlays back to their previous trend once the economy recovered. Balancing the budget is made impossible when the prevailing psychology among legislators and the media is that reductions in the growth of spending represent spending cuts.

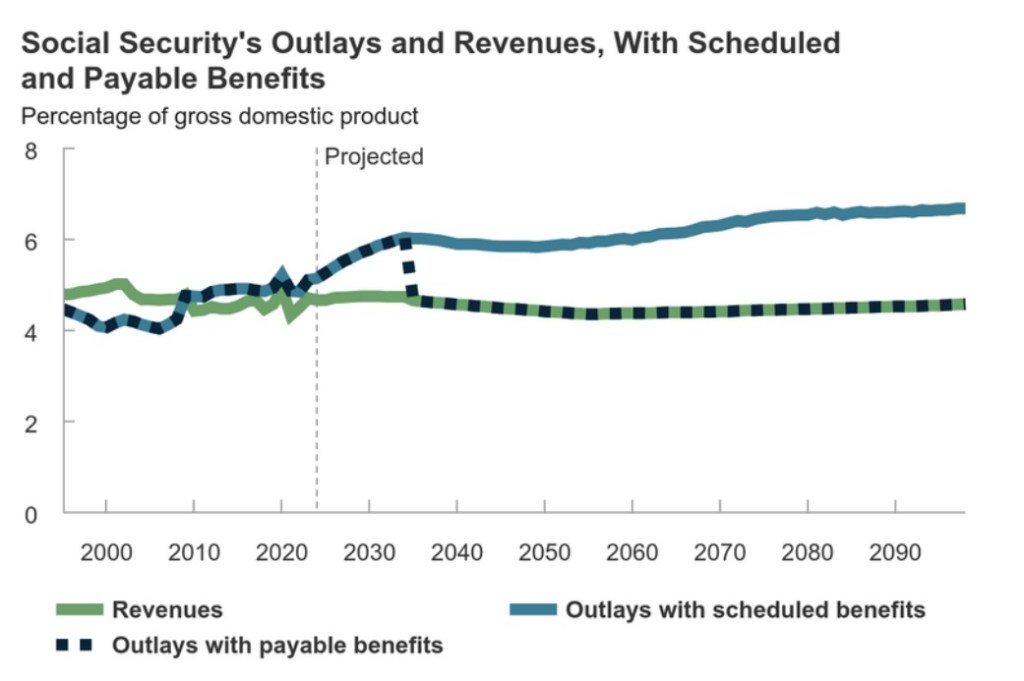

Federal spending is excessive on both the discretionary and mandatory sides of the budget. Ultimately, eliminating the budget deficit without allowing the 2017 Trump tax cuts to expire will require reform to mandatory entitlements like Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, as well as reductions across an array of discretionary programs.

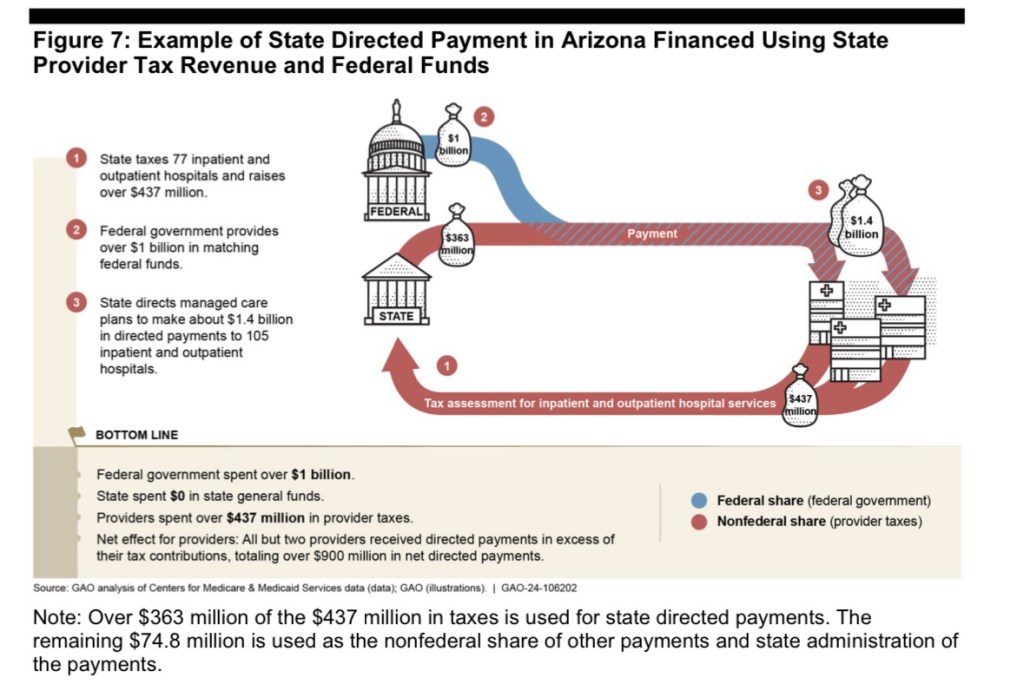

DOGE’s focus on fraud and waste extends to entitlements. At a minimum, the data and tracking systems in place at HHS and SSA are antiquated, sometimes inaccurate, and are highly susceptible to manipulation and fraud. Systems upgrades are likely to pay for themselves many times over.

But all indications are that it’s much worse than that. Social security numbers were issued to millions of illegal immigrants during the Biden Administration, and those enrollees were cleared for maximum benefits. There were a significant number of illegals enrolled in Medicaid and registered to vote. While some of these immigrants might be employed and contributing to the entitlement system, they should not be employed without legal status. Of course, one can defend these entitlement benefits on purely compassionate grounds, but the availability of benefits has served to attract a massive flow of illegal border crossings. This illustrates both the extent to which the entitlement system has been compromised as well as the breakdown of border security.

On the discretionary side of the budget, DOGE has identified an impressive array programs that were not just wasteful, but by turns ridiculous or politically motivated (for example, the bulk of USAID’s budget). Many of these funding initiatives belong on the chopping block, and components that might be worthwhile have been moved to agencies with related missions. In addition, authorized but unspent allocations have been identified that seem to have been held in reserve, and which now can be used to reduce the public debt.

Research Grants?

Of course, like the initial scale of the FDA layoffs, a few mistakes have and will be made by DOGE and agencies under DOGE’s guidance. Many believe another powerful argument against DOGE is the Trump Administration’s 15% limit on indirect costs as an add-on to NIH grants. Critics assert that this limit will hamstring U.S. scientific advancement. However, it won’t “kill” publicly funded research. As this article in Reason points out, historically public funding has not been critical to scientific advancement in the U.S. In fact, private funding accounts for the vast bulk of U.S. R&D, according to the Congressional Research Service. Moreover, it’s broadly acknowledged that indirect costs are subject to distortion, and that generous funding of those costs creates bad incentives and raises thorny questions about cross-subsidies across funders (15% is the rate at which charities typically fund indirect costs).

No doubt some elite research universities will suffer declines in grants, but their case is weakened politically by a combination of lax control over anti-Semitic protests on campus, the growing unpopularity of DEI initiatives in education, and public awareness of the huge endowments over which these universities preside. Nevertheless, I won’t be surprised to see the 15% limit on indirect research costs revised upward somewhat.

More DOGE Please

I’ve criticized the numbers posted on DOGE’s website elsewhere. They could do a much better job of categorizing and reporting the savings they’ve achieved, and they have far to go before meeting the goals stated by Elon Musk. Be that as it may, DOGE is making progress. Here is a report on a few of the latest cuts.

As I’ve emphasized on numerous occasions, the federal government is a strangling mass of tentacles, squeezing excessive resources out of the private sector and suffocating producers with an endless catalogue of burdensome rules. There are many examples of systemic waste taking place within the federal bureaucracy. For example, since its creation by Jimmy Carter, the Department of Education has managed to piss away trillions of dollars while student performance has declined. The Small Business Administration has doled out millions of dollars in subsidized loans to super-centenarians as well as children. The U.S. Postal Service keeps losing money and mail while deliveries slow to a crawl. Big projects become mired in endless iterations of reviews and revisions, such as Obama’s infrastructure plan and Joe Biden’s infrastructure and rural broadband initiative.

And again, regulatory agencies are often our worst enemies, imposing burdensome requirements with which only the largest industry players can afford to comply. Indeed, the savings achieved through the DOGE process might pale in comparison to the resources that could be liberated by rationalizing the tangle of regulations now choking private business.

A significant narrowing of the budget deficit would be a major accomplishment for DOGE. Even one-time savings to help pay down the public debt are worthwhile. In this latter regard, I hope DOGE’s work with the Department of Interior helps facilitate the sale of dormant federal assets. This includes land (not parks) and buildings worth literally trillions of dollars, and sometimes costing billions annually to maintain.