Tags

Absolute Advantage, AGI, Alignment, American Equity Fund, Antitrust, ChatGPT, Chris Edwards, Comparative advantage, consumption tax, David Schizer, Defense Production Act, Direct Taxes, Inequality, Maxwell Tabarrok, Michael Munger, Michael Strain, Moore v. United States, Moore’s Law, Open AI, Patrick Hedger, Sam Altman, Scarcity, Scott Sumner, Sixteenth Amendment, Steven Calabresi, Tax Incidence, ULTRA Tax, Wealth Tax

As of February 2026, I’m adding this short preamble to a few older posts on the subject of AI and future prospects for human labor. In the original post below (and a few others), I overstated the case that the law of comparative advantage would assure a continued role for humans in production. I still think the case is strong, mind you, but now I’m convinced that the outcome depends on elasticities of input substitution and how those elasticities might shift given the advent of AI-augmented capital. You can read my most recent thoughts on the matter here.

____________________________________________

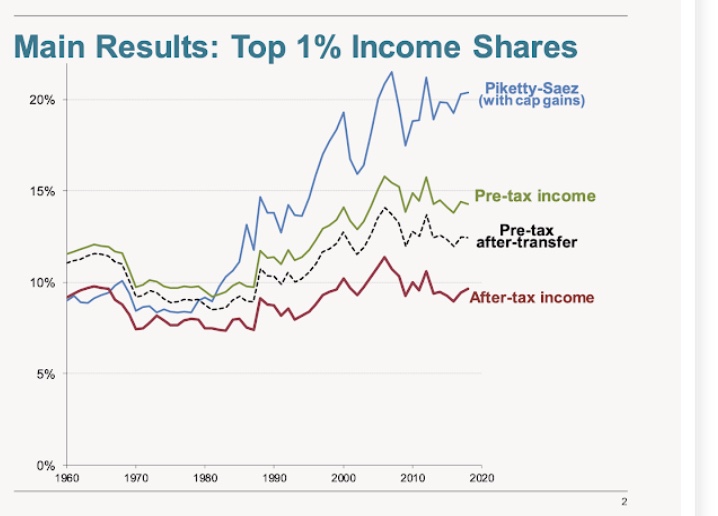

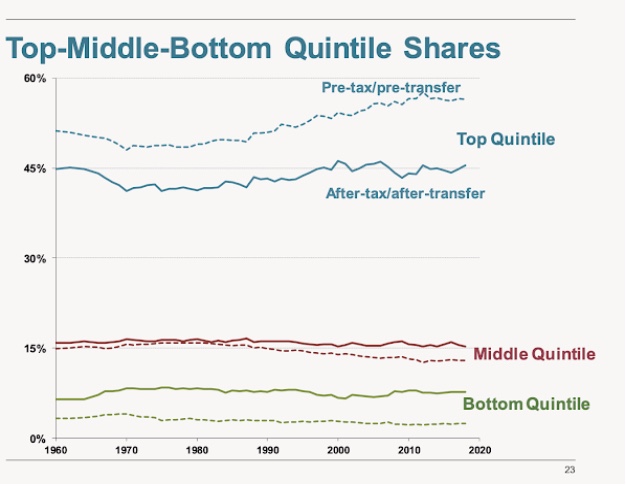

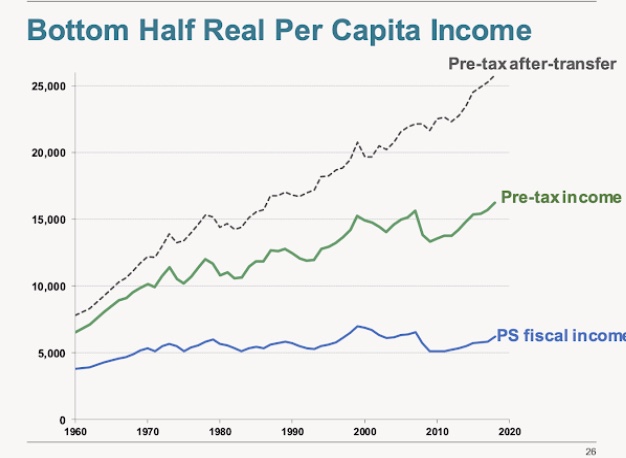

In this case, the “A” stands for Altman. Now Sam Altman is no slouch, but he’s taken a few ill-considered positions on public policy. Altman, the CEO of Open AI, wrote a blog post back in 2021 entitled “Moore’s Law For Everything” in which he predicted that AI will feed an explosion of economic growth. He also said AI will put a great many people out of work and drive down the price of certain kinds of labor. Furthermore, he fears that the accessibility of AI will be heavily skewed against the lowest socioeconomic classes. In later interviews (see here and here), Altman is somewhat demure about those predictions, but the general outline is the same: despite exceptional growth of GDP and wealth, he envisions job losses, an underclass of AI-illiterates, and a greater degree of income and wealth inequality.

Not Quite Like That

We’ve yet to see an explosion of growth, but it’s still very early in the AI revolution. The next several years will be telling. AI holds the potential to vastly increase our production possibilities over the course of the next few decades. For that and other reasons, I don’t buy the more dismal aspects of Altman’s scenario, as my last two posts make clear (here and here).

There will be plenty of jobs for people because humans will have comparative advantages in various areas of production. AI agents might have absolute advantages across most or even all jobs, but a rational deployment would have AI agents specialize only where they have a comparative advantage.

Scarcity will not be the sort of anachronism envisioned by some AI futurists, Altman included, and scarcity of AI agents (and their inputs) will necessitate their specialization in certain tasks. The demand for AI agents will be quite high, and their energy and “compute” requirements will be massive. AI agents will face extremely high opportunity costs in other tasks, leaving many occupations open for human labor, to say nothing of abundant opportunities for human-AI collaboration.

However, I don’t dismiss the likelihood of disruptions in markets for certain kinds of labor if the AI revolution proceeds as rapidly as Altman thinks it will. Many workers would be displaced, and it would take time, training, and a willingness to adapt for them to find new opportunities. But new kinds of jobs for people will emerge with time as AI is embedded throughout the economy.

Altman’s Rx

Altman’s somewhat pessimistic outlook for human employment and inequality leads him to make a couple of recommendations:

1) Ownership of capital must be more broadly distributed.

2) Capital and land must be taxed, potentially replacing income taxes, but primarily to fund equity investments for all Americans.

Here I agree with the spirit of #1. Broad ownership of capital is desirable. It allows greater participation in the capitalist system, which fosters political and economic stability. And wider access to capital, whether owned or not, allows a greater release of entrepreneurial energy. It also diversifies incomes and reduces economic dependency.

Altman proposes the creation of an American Equity Fund (AEF) to hold the proceeds of taxes on land and corporate assets for the benefit of all Americans. I’ll get to the taxes in a moment, but in discussing the importance of educating the public on the benefits of compounding, Altman seems to imply that assets in AEF would be held in individual accounts, as opposed to a single “public” account controlled by the federal government. Individual accounts would be far preferable, but it’s not clear how much control Altman would grant individuals in managing their accounts.

To Kill a Golden Goose

Taxes on capital are problematic. Capital can only be accumulated over time by saving out of income. Thus, as Michael Munger points out, as a general proposition under an income tax, all capital has already been taxed once. And we tax the income from capital at both the corporate and individual level. So corporate income is already double taxed: corporate profits are taxed along with dividend payments to shareholders.

Altman proposed in his 2021 blog post to levy a tax of 2.5% on the market value of publicly-traded corporations each year. The tax would be payable in cash or in corporate shares to be placed into the AEF. The latter would establish a kind of UnLiquidated Tax Reserve Accounts (ULTRA), which Munger discusses in the article linked above (my bracketed x% in the quote here):

“Instead of taking [x%] of the liquidated value of the wealth, the state would simply take ownership of the wealth, in place. An ULTRA is a ‘notional equity interest.’ The government literally takes a portion of the value of the asset; that value will be paid to the state when the asset is sold. Now, it is only a ‘notional’ stake, in the sense that no shared right of control or voting rights exists. But for those who advocate for ULTRAs, in any situation where tax agencies are authorized to tax an asset today, but cannot because there is no evaluation event, the taxpayer could be made to pay with an ULTRA rather than with cash.”

This solves all sorts of administrative problems associated with wealth taxes, but it is draconian nevertheless. Munger quotes an example of a successful, privately-held business subject to a 2% wealth tax every year in the form of an ULTRA. After 20 years, the government owns more than a third of the company’s value. That represents a substantial penalty for success! However, the incidence of such a tax might fall more on workers and customers and less on business owners. And Altman would tax corporations more heavily than in Munger’s example.

A tax on wealth essentially penalizes thrift, reduces capital accumulation, and diminishes productivity and real wages. But another fundamental reason that taxes on capital should be low is that the supply of capital is elastic. A tax on capital discourages saving and encourages capital flight. The use of avoidance schemes will proliferate, and there will be intense pressure to carve out special exemptions.

A Regressive Dimension

Another drawback of a wealth tax is its regressivity with respect to returns on capital. To see this, we can convert a tax on wealth to an equivalent income tax on returns. Here is Chris Edwards on that point:

“Suppose a person received a pretax return of 6 percent on corporate equities. An annual wealth tax of 2 percent would effectively reduce that return to 4 percent, which would be like a 33 percent income tax—and that would be on top of the current federal individual income tax, which has a top rate of 37 percent.”

… The effect is to impose lower effective tax rates on higher‐yielding assets, and vice versa. If equities produced returns of 8 percent, a 2 percent wealth tax would be like a 25 percent income tax. But if equities produced returns of 4 percent, the wealth tax would be like a 50 percent income tax. People with the lowest returns would get hit with the highest tax rates, and even people losing money would have to pay the wealth tax.“

Edwards notes the extreme inefficiency of wealth taxes demonstrated by the experience of a number of OECD countries. There are better ways to increase revenue and the progressivity of taxes. The best alternative is a tax on consumption, which rewards saving and capital accumulation, promoting higher wages and economic growth. Edwards dedicates a lengthy section of his paper to the superiority of a consumption tax.

Is a Wealth Tax Constitutional?

The constitutionality of a wealth tax is questionable as well. Steven Calabresi and David Schizer (C&S) contend that a federal wealth tax would qualify as a direct tax subject to the rule of apportionment, which would also apply to a federal tax on land. That is, under the U.S. Constitution, these kinds of taxes would have to be the same amount per capita in every state. Thus, higher tax rates would be necessary in less wealthy states.

C&S also note a major distinction between taxes on the value of wealth relative to income, excise, import, and consumption taxes. The latter are all triggered by transactions entered into voluntarily. They are avoidable in that sense, but not wealth taxes. Moreover, C&S believe the founders’ intent was to rely on direct taxes only as a backstop during wartime.

The recent Supreme Court decision in Moore v. United States created doubt as to whether the Court had set a precedent in favor of a potential wealth tax. According to earlier precedent, the Constitution forbade the “laying of taxes” on “unrealized” income or changes in wealth. However, in Moore, the Court ruled that undistributed profits from an ownership interest in a foreign business are taxable under the mandatory repatriation tax, signed into law by President Trump in 2017 as part of his tax overhaul package. But Justice Kavanaugh, who wrote the majority opinion, stated that the ruling was based on the foreign company’s status as a pass-through entity. The Wall Street Journal says of the decision:

“Five Justices open the door to taxing unrealized gains in assets. Democrats will walk through it.”

In a brief post, Calabrisi laments Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s expansive view of the federal government’s taxing authority under the Sixteenth Amendment, which might well be shared by the Biden Administration. But the Wall Street Journal piece also describes Kavanaugh’s admonition regarding any expectation of a broader application of the Moore opinion:

“Justice Kavanaugh does issue a warning that ‘the Due Process Clause proscribes arbitrary attribution’ of undistributed income to shareholders. And he writes that his opinion should not ‘be read to authorize any hypothetical congressional effort to tax both an entity and its shareholders or partners on the same undistributed income realized by the entity.’”

Growth Is the Way, Not Taxes

AI growth will lead to rapid improvements in labor productivity and real wages in many occupations, despite a painful transition for some workers requiring occupational realignment and periods of unemployment and training. However, people will retain comparative advantages over AI agents in a number of existing occupations. Other workers will find that AI allows them to shift their efforts toward higher-value or even new aspects of their jobs. Along the same lines, there will be a huge variety of new occupations made possible by AI of which we’re only now catching the slightest glimpse. Michael Strain has emphasized this aspect of technological diffusion, noting that 60% of the jobs performed in 2018 did not exist in 1940. In fact, few of those “new” jobs could have been imagined in 1940.

AI entrepreneurs and AI investors will certainly capture a disproportionate share of gains from an AI revolution. Of course, they’ll have created a disproportionate share of that wealth. It might well skew the distribution of wealth in their favor, but that does not reflect negatively on the market process driving the outcome, especially because it will also give rise to widespread gains in living standards.

Altman goes wrong in proposing tax-funded redistribution of equity shares. Those taxes would slow AI development and deployment, reduce economic growth, and produce fewer new opportunities for workers. The surest way to effect a broader distribution of equity capital, and of equity in AI assets, is to encourage innovation, economic growth, and saving. Taxing capital more heavily is a very bad way to do that, whether from heavier taxes on income from capital, new taxes on unrealized gains, or (worst of all) from taxes on the value of capital, including ULTRA taxes.

Altman is right, however, to bemoan the narrow ownership of capital. As I mentioned above, he’s also on-target in saying that most people do not fully appreciate the benefits of thrift and the miracle of compounding. That represents both a failure of education and our calamitously high rate of time preference as a society. Perhaps the former can be fixed! However, thrift is a decision best left in private hands, especially to the extent that AI stimulates rapid income growth.

Killer Regulation

Altman also supports AI regulation, and I’ll cut him some slack by noting that his motives might not be of the usual rent-seeking variety. Maybe. Anyway, he’ll get some form of his wish, as legislators are scrambling to draft a “roadmap” for regulating AI. Some are calling for billions of federal outlays to “support” AI development, with a likely and ill-advised effort to “direct” that development as well. That is hardly necessary given the level of private investment AI is already attracting. Other “roadmap” proposals call for export controls on AI and protections for the film and recording industries.

These proposals are fueled by fears about AI, which run the gamut from widespread unemployment to existential risks to humanity. Considerable attention has been devoted to the alignment of AI agents with human interests and well being, but this has emerged largely within the AI development community itself. There are many alignment optimists, however, and still others who decry any race between tech giants to bring superhuman generative AI to market.

The Biden Administration stepped in last fall with an executive order on AI under emergency powers established by the Defense Production Act. The order ranges more broadly than national defense might necessitate, and it could have damaging consequences. Much of the order is redundant with respect to practices already followed by AI developers. It requires federal oversight over all so-called “foundation models” (e.g., ChatGPT), including safety tests and other “critical information”. These requirements are to be followed by the establishment of additional federal safety standards. This will almost certainly hamstring investment and development of AI, especially by smaller competitors.

Patrick Hedger discusses the destructive consequences of attempts to level the competitive AI playing field via regulation and antitrust actions. Traditionally, regulation tends to entrench large players who can best afford heavy compliance costs and influence regulatory decisions. Antitrust actions also impose huge costs on firms and can result in diminished value for investors in AI start-ups that might otherwise thrive as takeover targets.

Conclusion

Sam Altman’s vision of funding a redistribution of equity capital via taxes on wealth suffers from serious flaws. For one thing, it seems to view AI as a sort of exogenous boon to productivity, wholly independent of investment incentives. Taxing capital would inhibit investment in new capital (and in AI), diminish growth, and thwart the very goal of broad ownership Altman wishes to promote. Any effort to tax capital at a global level (which Altman supports) is probably doomed to failure, and that’s a good thing. The burden of taxes on capital at the corporate level would largely be shifted to workers and consumers, pushing real wages down and prices up relative to market outcomes.

Low taxes on income and especially on capital, together with light regulation, promote saving, capital investment, economic growth, higher real wages, and lower prices. For AI, like all capital investment, public policy should focus on encouraging “aligned” development and deployment of AI assets. A consumption tax would be far more efficient than wealth or capital taxes in that respect, and more effective in generating revenue. Policies that promote growth are the best prescription for broadening the distribution of capital ownership.