Tags

Backup Power, Battery Technology, Capacity Factors, Center of the American Experiment, Climate Change, Dante’s Inferno, Dispatchable Power, Dormant Capital, Fossil Furls, Green Energy, Imposed Costs, Industrial Planning, Isaac Orr, Mackinac Center for Public Policy, Malinvestment, Mitch Rolling, Power Outages, Power Tramsmission, Solar Energy, Space Based Solar Power, Subsidies, Wind Energy

This is a first for me…. The following is partly excerpted from a post of two weeks ago, but I’ve made a number of edits and additions. The original post was way too long. This is a bit shorter, and I hope it distills a key message.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Failures of industrial policies are nothing new, but the current manipulation of electric power generation by government in favor of renewable energy technologies is egregious. These interventions are a reaction to an overwrought climate crisis narrative, but they have many shortcomings and risks of their own. Chief among them is whether the power grid will be capable of meeting current and future demand for power while relying heavily on variable resources, namely wind and sunshine. The variability implies idle and drastically underutilized hours every day without any ability to call upon the assets to produce when needed.

The variability is vividly illustrated by the chart above showing a representative daily profile of power demand versus wind and solar output. Below, with apologies to Dante, I describe the energy hellscape into which we’re being driven on the horns of irrational capital outlays. These projects would be flatly rejected by any rational investor but for the massive subsidies afforded by government.

The First Circle of Dormancy: Low Utilization

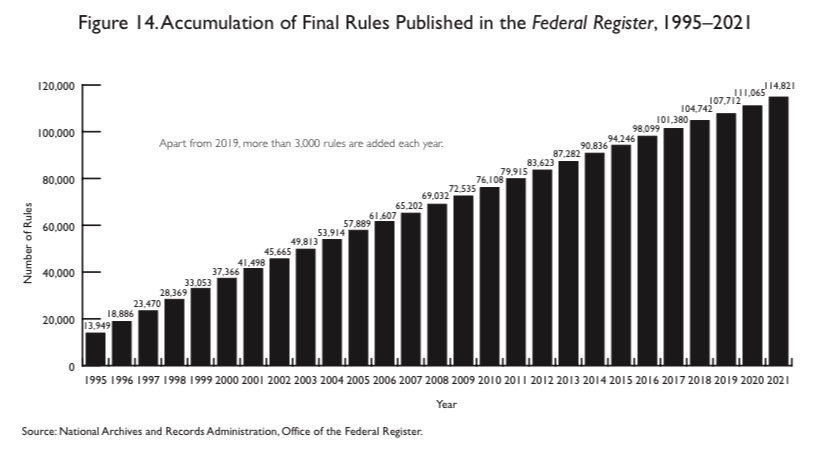

Wind and solar power assets have relatively low rates of utilization due to the intermittency of wind and sunshine. Capacity factors for wind turbines averaged almost 36% in the U.S. in 2022, while solar facilities averaged only about 24%. This compared with nuclear power at almost 93%, natural gas (66%), and coal (48%).

Despite their low rates of utilization, new wind and solar facilities are always touted at their full nameplate capacity. We hear a great deal about “additions to capacity”, which overstate the actual power-generating potential by factors of three to four times. More importantly, this also means wind and solar power costs per unit of output are often vastly understated. These assets contribute less economic value to the electric grid than more heavily utilized generating assets.

Sometimes wind and solar facilities are completely idle or dormant. Sometimes they operate at just a fraction of capacity. I will use the terms “idle” and dormant” euphemistically in what follows to mean assets operating not just at low levels of utilization, but for those prone to low utilization and also falling within the Second Circle of Dormancy.

The Second Circle of Dormancy: Non-Dispatchability

The First Circle of Dormancy might be more like a Purgatory than a Hell. That’s because relatively low average utilization of an asset could be justifiable if demand is subject to large fluctuations. This is the often case, as with assets like roads, bridges, restaurants, amusement parks, and many others. However, capital invested in wind and solar facilities is idle on an uncontrollable basis, which is more truly condemnable. Wind and solar do not provide “dispatchable” power, meaning they are not “on call” in any sense during idle or less productive periods. Not only is their power output uncontrollable, it is not entirely predictable.

Again, variable but controllable utilization allows flexibility and risk mitigation in many applications. But when utilization levels are uncontrollable, the capital in question has greatly diminished value to the power grid and to power customers relative to dispatchable sources having equivalent capacity and utilization. It’s no wonder that low utilization, variability, and non-dispatchability are underemphasized or omitted by promoters of wind and solar energy. This sort of uncontrollable down-time is a drain on real economic returns to capital.

The Third Circle of Dormancy: Transmission Infrastructure

The idleness that besets the real economic returns to wind and solar power generation extends to the transmission facilities necessary for getting power to the grid. Transmission facilities are costly, but that cost is magnified by the broad spatial distribution of wind and solar generating units. Transmission from offshore facilities is particularly complex. When wind turbines and solar panels are dormant, so are the transmission facilities needed to reach them. Thus, low utilization and the non-dispatchability of those units diminishes the value of the capital that must be committed for both power generation and its transmission.

The Fourth Circle of Dormancy: Backup Power Assets

The reliability of the grid requires that any commitment to variable wind and solar power must also include a commitment to back-up capacity. As another example, consider shipping concerns that are now experimenting with sails on cargo ships. What is the economic value of such a ship without back-up power? Can you imagine these vessels drifting in the equatorial calms for days on end? Even light winds would slow the transport of goods significantly. Idle, non–dispatchable capital, is unproductive capital.

Likewise, solar-powered signage can underperform or fail over the course of several dark, wintry days, even with battery backup. The signage is more reliable and valuable when it is backed-up by another power source. But again, idle, non-dispatchable capital is unproductive capital.

The needed provision of backup power sources represents an imposed cost of wind and solar, which is built into the cost estimates shown in a section below. But here’s another case of dormancy: some part of the capital commitment, either primary energy sources or the needed backups, will be idle regardless of wind and solar conditions… all the time. Of course, back-up power facilities should be dispatchable because they must serve an insurance function. Backup power therefore has value in preserving the stability of the grid even while completely idle. However, at best that value offsets a small part of the social loss inherent in primary reliance on variable and non-dispatchable power sources.

We can’t wholly “replace” dispatchable generating capacity with renewables without serious negative consequences. At the same time, maintaining existing dispatchable power sources as backup carries a considerable cost at the margin for wind and solar. At a minimum, it requires normal maintenance on dispatchable generators, periodic replacement of components, and an inventory of fuel. If renewables are intended to meet growth in power demand, the imposed cost is far greater because backup sources for growth would require investment in new dispatchable capacity.

The Fifth Circle of Dormancy: Outages

The pursuit of net-zero carbon emissions via wind and solar power creates uncontrollably dormant capital, which increasingly lacks adequate backup power. Providing that backup should be a priority, but it’s not.

Perhaps much worse than the cost of providing backup power sources is the risk and imposed cost of grid instability in their absence. That cost would be borne by users in the form of outages. Users are placed at increasing risk of losing power at home, at the office and factories, at stores, in transit, and at hospitals. This can occur at peak hours or under potentially dangerous circumstances like frigid or hot weather.

Outage risks include another kind of idle capital: the potential for economy-wide shutdowns across a particular region of all electrified physical capital. Not only can grid failure lead to economy-wide idle capital, but this risk transforms all capital powered by electricity into non-dispatchable productive capacity.

Reliance on wind and solar power makes backup capacity an imperative. Better still, just scuttle the wind and solar binge and provide for growth with reliable sources of power!

Quantifying Infernal Costs

A “grid report card“ from the Mackinac Center for Public Policy gets right to the crux of the imposed-cost problem:

“… the more renewable generation facilities you build, the more it costs the system to make up for their variability, and the less value they provide to electricity markets.”

The report card uses cost estimates for Michigan from the Center of the American Experiment. Here are the report’s average costs per MWh through 2050, including the imposed costs of backup power:

—Existing coal plant: $33/MWh

—Existing gas-powered: $22

— New wind: $180

—New solar: $278

—New nuclear reactor (light water): $74

—Small modular reactor: $185

—New coal plant: $106 with carbon capture and storage (CCS)

—New natural gas: $64 with CCS

It’s should be no surprise that existing coal and gas facilities are the most cost effective. Preserve them! Of the new installations, natural gas is the least costly, followed by the light water reactor and coal. New wind and solar capacity are particularly costly.

Proponents of net zero are loath to recognize the imposed cost of backup power for two reasons. First, it is a real cost that can be avoided by society only at the risk of grid instability, something they’d like to ignore. To them, it represents something of an avoidable external cost. Second, at present, backup dispatchable power would almost certainly entail CO2 emissions, violating the net zero dictum. But in attempting to address a presumed externality (climate warming) by granting generous subsidies to wind and solar investors, the government and NGOs induce an imposed cost on society with far more serious and immediate consequences.

Deadly Sin: Subsidizing Dormant Capital

Wind and solar capital outlays are funded via combinations of private investment and public subsidies, and the former is very much contingent on the latter. That’s because the flood of subsidies is what allows private investors a chance to profit from uncontrollably dormant capital. Wind and solar power are far more heavily subsidized than fossil fuels, as noted by Mitch Rolling and Isaac Orr:

“In 2022, wind and solar generators received three and eighteen times more subsidies per MWh, respectively, than natural gas, coal, and nuclear generators combined. Solar is the clear leader, receiving anywhere from $50 to $80 per MWh over the last five years, whereas wind is a distant second at $8 to $10 per MWh …. Renewable energy sources like wind and solar are largely dependent on these subsidies, which have been ongoing for 30 years with no end in sight.”

But even generous subsidies often aren’t enough to ensure financial viability. Rent-enabled malinvestments like these crowd out genuinely productive capital formation. Those lost opportunities span the economy and are not limited to power plants that might otherwise have used fossil fuels.

Despite billions of dollars in “green energy” subsidies, bankruptcy has been all too common among wind and solar firms. That financial instability demonstrates the uneconomic nature of many wind and solar investments. Bankruptcy pleadings represent yet another way investors are insulated against wind and solar losses.

Subsidized Off-Hour (Wasted) Output

This almost deserves a sixth circle, except that it’s not about dormancy. Wind and solar power are sometimes available when they’re not needed, in which case the power goes unused because we lack effective power storage technology. Battery technology has a long way to go before it can overcome this problem.

When wind and solar facilities generate unused and wasted power during off-hours, their operators are nevertheless paid for that power by selling it into the grid where it goes unused. It’s another subsidy to wind and solar power producers, and one that undermines incentives for investment in batteries.

A Path To Redemption

Space-based solar power beamed to earth may become a viable alternative to terrestrial wind and solar production within a decade or so. The key advantages would be constancy and the lack of an atmospheric filter on available solar energy, producing power 13 times as efficiently as earth-bound solar panels. From the last link:

“The intermittent nature of terrestrial renewable power generation is a major concern, as other types of energy generation are needed to ensure that lights stay on during unfavorable weather. Currently, electrical grids rely either on nuclear plants or gas and coal fired power stations as a backup…. “

Construction of collection platforms in geostationary orbit will take time, of course, but development of space-based solar should be a higher priority than blanketing vast tracts of land with inefficient solar panels while putting power users at risk of outages.

No Sympathy for Malinvestment

This post identified five ways in which investments in wind and solar power create frequent and often extended periods of damnably dormant physical capital:

- Low Utilization

- Nondispatchable Utilization

- Idle Transmission Infrastructure

- Idle Backup Generators

- Outages of All Electrified Capital

Power demand is expected to soar given the coming explosion in AI applications, and especially if the heavily-subsidized and mandated transition to EVs comes to pass. But that growth in demand will not and cannot be met by relying solely on renewable energy sources. Their variability implies substantial idle capacity, higher costs, and service interruptions. Such a massive deployment of dormant capital represents an enormous waste of resources, and the sad fact is it’s been underway for some time.

In the years ahead, the net-zero objective will motivate more bungled industrial planning as a substitute for market-driven forces. Costs will be driven higher by the imposed costs of backup capacity and/or outages. Ratepayers, taxpayers, and innocents will all share these burdens.

Creating idle, non-dispatchable physical capital is malinvestment which diminishes future economic growth. The boom in wind and solar activity began in earnest during the era of negative real interest rates. Today’s higher rates might slow the malinvestment, but they won’t bring it to an end without a substantial shift in the political landscape. Instead, taxpayers will shoulder an even greater burden, as will ratepayers whose power providers are guaranteed returns on their regulated rate bases.