See my March 28 update here.

What follows is an exercise intended to put the coronavirus in perspective as we move through a crucial phase in the U.S. I believe it’s more informative than speculative. However, I’m relying on several pieces of information in establishing bounds on how the caseload and mortality rate will play out over the next few months: the experience abroad; domestic developments thus far; risk mitigation; prospective treatments; and some mathematics.

Pandemic Progressions

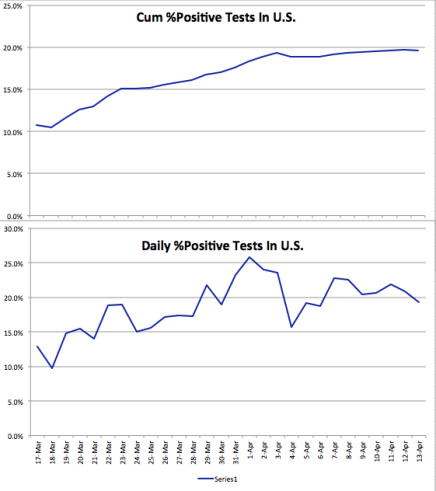

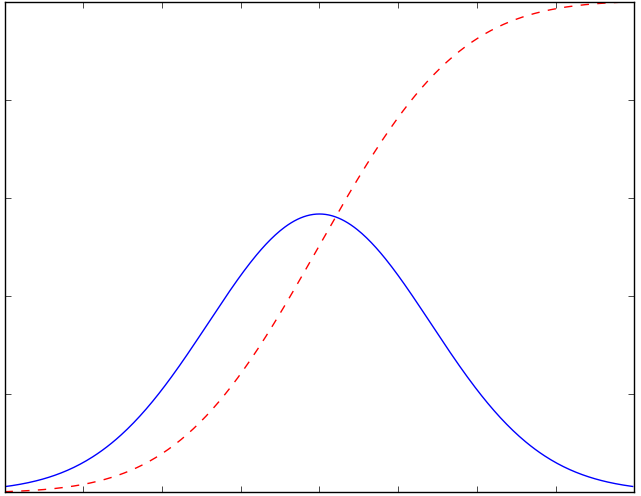

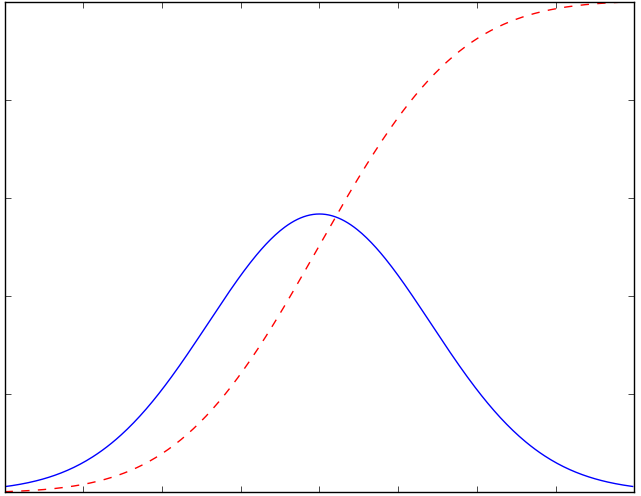

Despite all the warnings we’ve heard about exponential growth in the number of infections, that is something characterizing only the earliest stages of epidemics. These episodes invariably follow a growth curve that accelerates for a time before tapering. The total number of individuals infected eventually flattens, like the top of the dashed red line in the chart below. Think of the blue line’s height as showing the number of new positive diagnoses each day. New cases (blue) peak as the slope of the red line, total positive diagnoses, begins to decrease. The blue line is the one we’d like to flatten. That’s because once the number of new cases exceeds a certain threshold, medical resources can no longer handle the load. Nevertheless, I’ll focus on the red line and how it’s growth accelerates and then decelerates. Where are various countries on that curve?

I’ve been using the interactive tool at the Insights and Outliers web site to view curves like the red line above, by country. China and South Korea are at the top, where the line is flat, though I discount the Chinese numbers as quite likely manipulated. Italy is somewhere in the middle of the red curve — one hopes it will enter the deceleration phase soon, but it’s not clear from the numbers.

Setting Context

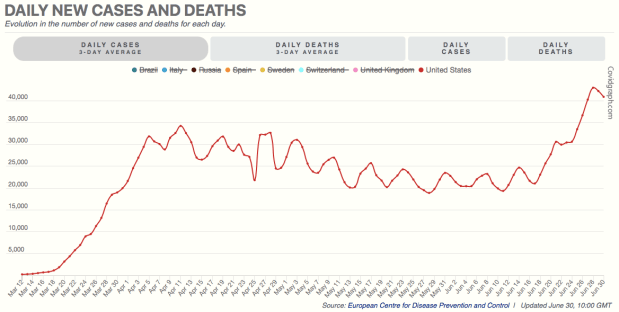

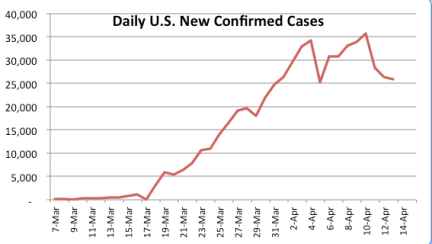

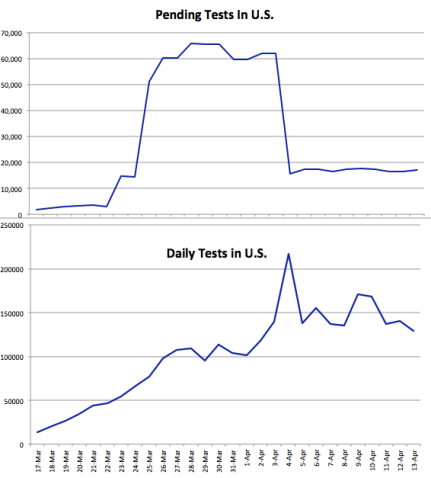

The U.S. caseload is accelerating; it will continue to accelerate until the availability of tests catches up with demand from individuals meeting the qualifications for testing. The delay in the availability of tests, which I mentioned in an earlier post, will exaggerate the acceleration in the number of diagnosed cases for another week, or perhaps a bit more. Some of those cases already existed, and we should have known about them before now. However, after starting high, the U.S. death rate from the virus is already well below the global death rate, suggesting that either 1) our testing is actually well ahead of the rest of the world; 2) our Covid-19 mortality is, and will be, lower than the rest of the world; or 3) deaths in the U.S. will increase much faster than new diagnoses over the next few weeks. I seriously doubt the latter given the high quality of U.S. health care, the time of year, and the promising treatments that have recently been approved for use.

I expect the daily number of new cases in the U.S. to fall after the “catch-up” in testing. That’s based on a combination of things: first, the time from infection to first symptoms can be up to about 14 days, but the mean is just five days. Second, in the U.S., we began to practice “social distancing” and “self-quarantine” in earnest just this past week. Among those infected before this week, those who develop symptoms serious enough to notice will know before the end of March. But people are still out trying to take care of business. Some of those people will catch the virus, and there will be secondary infections of family members or others in close proximity to individuals diagnosed earlier. It will take an additional week, accounting for overlap, for infections among that cohort to mature. Nevertheless, over the next three weeks, the number of infections transmitted to new “hosts” will fall drastically with social distancing, as each of us comes into contact with fewer people.

Third, the transmissibility of the virus will decrease with rising temperatures, more direct sunlight, and higher absolute humidity. See my post on the topic here. I know, I know, skeptics wag their fingers and say, “Covid-19 is not the same as the flu virus”, and they’re right! It has some similarities, however: a so-called “envelope” lipid membrane, transmissability via fine aerosols or larger droplets expelled into the air by infected individuals, and symptoms that are similar, except for shortness of breath with Covid-19. And like the flu, the new virus seems to be more virulent in cold, dry environments. If you cannot avoid contact with other individuals during your workday, if you have a large family at home, or if you live in quarters with a number of other individuals, it might be a good idea to keep your humidifier on or don’t air-condition aggressively. That’s an implication of this study and this study:

“The current spread suggests a degree of climate determination with Coronavirus displaying preference for cool and dry conditions. The predecessor SARS-CoV was linked to similar climate conditions.”

Bounding Expectations

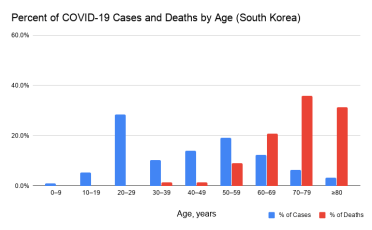

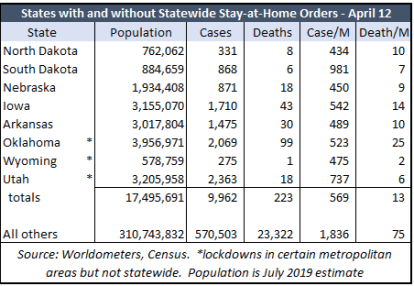

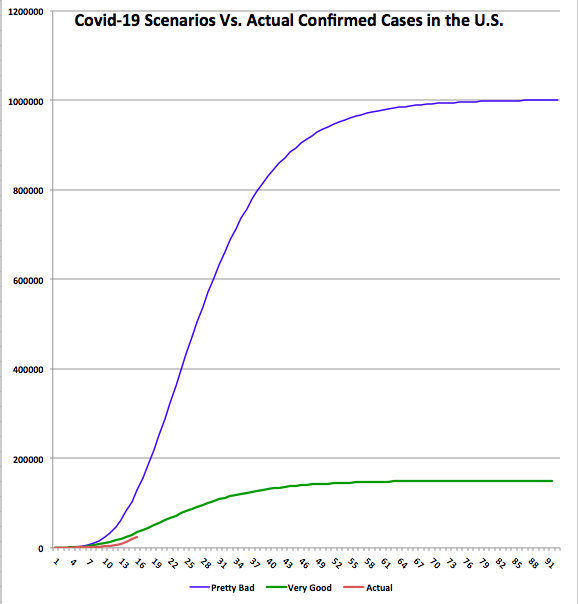

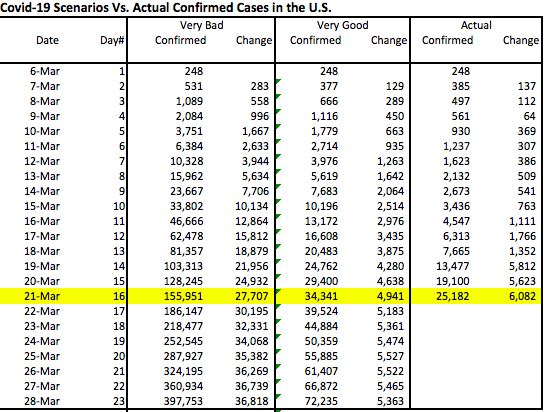

How high will the numbers go? I’ll start by establishing some “very good” and “very bad” scenarios for total confirmed cases. South Korea (where masks were used widely) has had an excellent experience thus far. The county’s cumulative confirmed cases flattened out at less than 0.017% (0.00017) of the total population. Assuming that 90% of cases are asymptomatic and undiagnosed, that would mean 0.17% (0.0017) of the South Korean population has been infected. If the U.S. experience is the same, we’d have a total of about 60,000 confirmed infections when our curve flattens. But I won’t be that optimistic — we’re at about 25,000 cases already and I think we’ll be at 60,000 cases within a week. Instead, I’ll define the “very good” scenario as 2.5x the South Korean outcome, or 150,000 confirmed cases.

For a “very bad” scenario one might look to Italy. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to say how much higher Italy’s case load will go before flattening. If it had flattened today (it didn’t), the rate of confirmed cases for the country would be 0.077% (0.00077). That yields 0.77% of the population including the undiagnosed at 90% of cases. Applying the same percentage to the U.S. would mean just over 250,000 confirmed cases. But again, for a really bad scenario, and because we don’t yet know how Italy’s experience will play out, let’s suppose Italy’s confirmed cases quadruple: For the U.S., using the same percentage of the population would imply just over 1 million confirmed cases, or about 1.6% of the population. That yields a total infected population of 10 million.

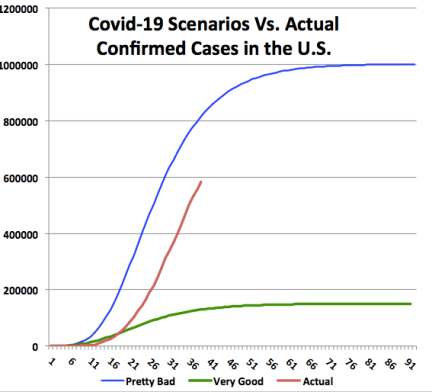

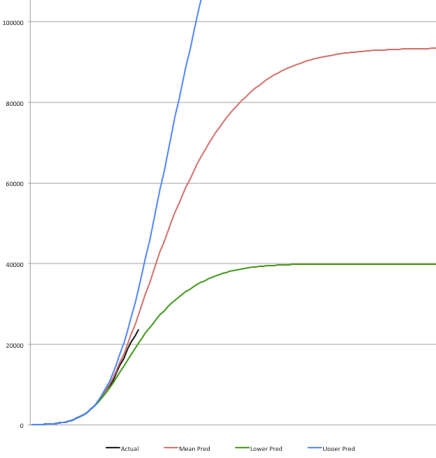

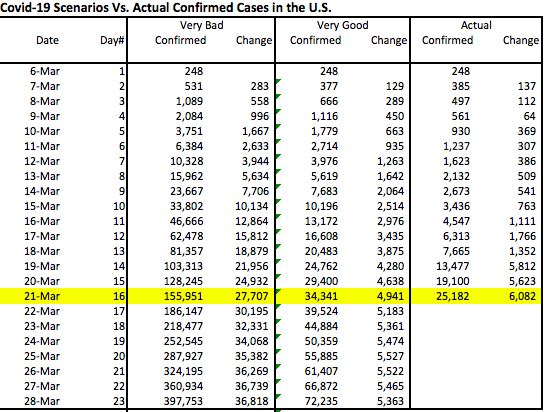

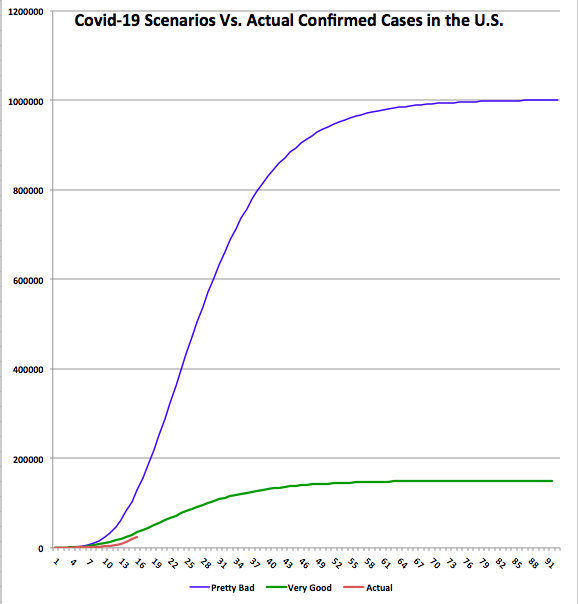

I’ve illustrated these “very good” and “very bad” scenarios in the chart below as Gompertz curves, a form of sigmoid function or s-curve. First, a couple of caveats: Please note that this represents a “first wave” of the virus, as it were. I do not dismiss the possibility of a second wave should we relax our nonprescription safeguards prematurely, and obviously the chart does not speak to a return of the virus in the fall. Also, these are just two examples that allow us to examine the implications of extreme outcomes. I could have varied the timing, growth, and end-outcome in other ways, but I think the following is instructive.

The chart shows cumulative confirmed cases for each scenario. It also shows the actual confirmed case total through March 21st, which is the shorter red line at the bottom. The data plotted begins on March 6, when there were 248 cases confirmed. The horizontal axis shows days elapsed since then. The accompanying table shows the same information through March 28th, a week from today.

There are a few things to note about the chart and table:

- The actual curve is still below the “very good” curve. If our experience proves to be marginally worse than the “very good” scenario, then we’ve already “caught-up” in terms of testing for Covid-19: the actual increase today is larger than the highest daily increases under that scenario. If our experience approaches the “very bad” scenario, then we are eight days behind in our testing. That is, today’s actual increase is about what that scenario would have predicted eight days ago.

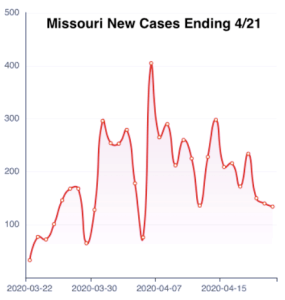

- Under the “very good” scenario, the daily increase in cases would peak by Friday, March 27. We’ve already exceeded that level of daily increase, but it will be encouraging if the daily increase doesn’t accelerate much more over the next few days. Under the “very bad” scenario, and given a full “catch-up”, the daily increase would peak about a week from now at approximately 37,000. That would be delayed if the catch-up process is more protracted.

- New cases flatten out within a couple of months under both scenarios. Under the “very good” scenario, new cases fall below 1,000 per day by April 21. Under the “very bad’ scenario, they don’t reach that level until Mid-May.

- In the next week (by March 28th), we will know a lot more about where we’re trending relative to these scenarios. I plan to provide an update later in the week or next weekend.

While it can’t be seen from the chart or the table, once the “catch-up” ends, if there really is a catch-up involved, the daily increase in cases might fall abruptly. That would be encouraging.

Other Thoughts

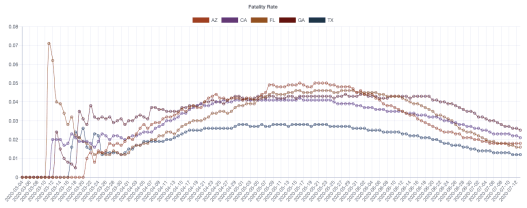

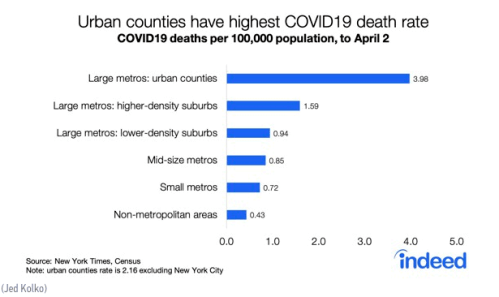

It’s also important to note that the experience within the U.S. might be as varied as what we see around the globe. For example, New York and Washington state seem to be hot spots. Cities with large international ports and flights are more likely to suffer relatively high infection rates. In contrast, St. Louis probably won’t have a comparable incidence of infection, as there are so few international flights terminating there.

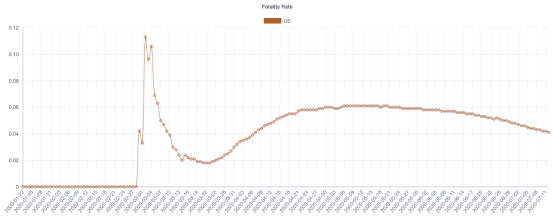

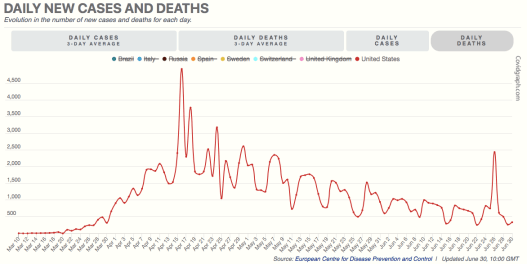

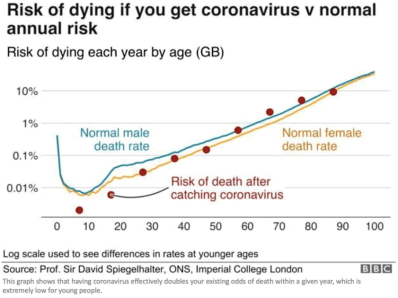

The global death rate from Covid-19 has been widely quoted as somewhere around 4%, but that came into question with the revelation of low mortality aboard the Diamond Princess, despite the many seniors aboard. And it appears that the death rate from coronavirus is declining in the U.S. This was noted here at Endless Metrics several days ago. It’s also discussed in some detail by Aaron Ginn in this excellent this Medium article. Again, the death rate will decline as our testing “catches-up”, if indeed it must, and it will decline with spring weather as well as treatments if they are effective. Ultimately, I’ll be surprised if it comes in at more than 1% of confirmed cases in the U.S., and I won’t be surprised if it’s much less. At 1% under the “very bad” scenario, the U.S. would have about 10,000 deaths associated with coronavirus, the large majority of which would be individuals older than 70 years of age with significant co-morbidities.

Conclusion

I hope this exercise proves useful to others in establishing a framing for what will ensue over the next few weeks. However, even the “very bad” scenario discussed above involves an infected share of the population of much less than we’ve heard we’re in for. Yet that scenario is far worse than Italy’s experience thus far, which most people consider pretty bad. For this reason, I am increasingly convinced that this pandemic will not prove to be the widespread calamity we’re still being told to expect. Those warning us might be alarmists, or perhaps they simply lack a sufficient level of numeracy.

This post was partly inspired by The Math of Epidemics by Willis Eschenbach, as well as Scott Alexander’s March 2nd post at Slate Star Codex. Also, see the Medium article by Aaron Ginn. It is a thorough examination of many aspects of the pandemic and very much aligned with my views. (Something is wrong with the link … I’ll try to fix it later.)

at WUWT