Tags

Agitprop, Americans for the Arts, Arts Education, Arts Funding, Corporation for Public Broadcasting, crowding out, DOGE, Exclusivity, Externalities, National Endowment for the Arts, Propaganda, Public goods, Public Radio, Samuel Andreyev, Subsidies, Thomas Jefferson

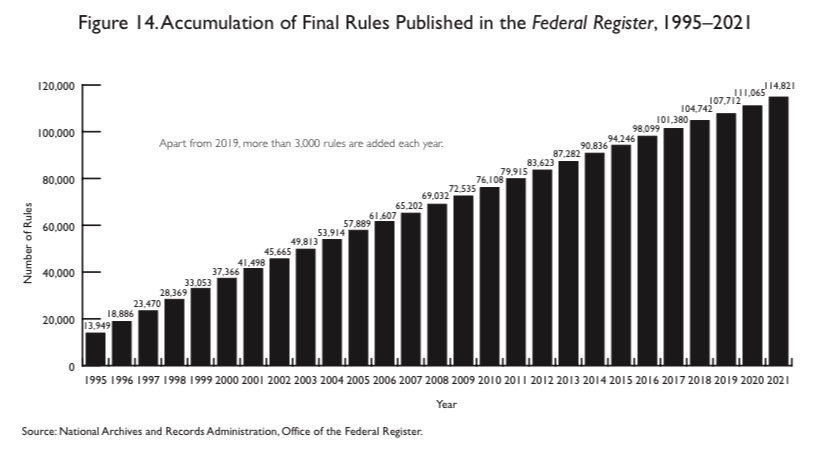

In a post a few years ago entitled “The National Endowment for Rich Farts”, I discussed a point that should be rather obvious: federal funding of the arts too often subsidizes the upper class, catering to their artistic tastes and underwriting a means through which they conduct social and professional networking. The topic is back in the news, with reports that the incoming Trump Administration, at the recommendation of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), will attempt to eliminate funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting.

Great Big Stuff and Crowding Out

To opponents of federal arts funding, public radio is probably the bête noire of arts organizations due to its left-wing political orientation and the general affluence of its subscriber base. However, public arts funding goes way beyond subsidies for public radio.

Large nonprofits receive the bulk of government arts funding. Despite claims to the contrary, these organizations won’t go broke without the gravy provided by public funding. The federal government contributes about 3% of the revenue taken in by non-profit arts organizations, according to Americans For the Arts. These organizations are already heavily subsidized: their surpluses are tax exempt and private contributions are tax deductible. Tax deductions are worth more to those in high income-tax brackets, and involvement in such visible organizations is highly prized by elites.

Furthermore, there is no evidence that additional government funding “multiplies” private giving. If anything, increases in public funding reduce private giving (and see here).

Public Funds for Private Gain

It’s often argued that government should subsidize the arts because art has the qualities of a public good, but that’s a false premise. A good can be classified as “public” only when its consumption is non-exclusive and non-rivalrous. Can individuals be excluded from enjoying music? Of course. Can they be excluded from viewing a theatrical performance, a film, or any other piece of visual art? Generally yes, and art exhibitions and artistic performances are nearly always subject to paid and limited attendance.

In some contexts art is, or can be made, less excludable. Architecture can be admired (or detested) by anyone on the street. So can public monuments and street art. A concert or play can be performed free of charge, perhaps at a large, outdoor venue. Amplification and large video monitors can make a big difference in terms of non-exclusion. Museums can offer admission to the general public at no charge. And we can broaden the definition of a work to include copies or reproductions that might be available via public display or broadcast (on NPR!).

All these steps will help increase exposure to the arts. But you can’t make it mandatory. People will always self-exclude because they can. So, in which cases should taxpayers bear the costs of art, and of making it less exclusive? On the spectrum of legitimate functions of government, it’s hard to rank this sort of activity highly.

A claim less absurd than the public goods argument is that art has some positive spillover effects, or externalities. It should therefore be subsidized or underwritten with public funds lest it be underprovided. Unfortunately, the spillover effects of a piece of art (where relevant) are not always positive. After all, tastes vary considerably. One man’s art can be another man’s annoyance or provocation. This undermines the case for public funding, at least for art that is controversial in nature.

Perhaps a better interpretation of art externalities is that exposure to the arts has positive spillover effects. Thus, additional art confers benefits to society above and beyond the edification of those exposed to it. Perhaps it makes us nicer and more interesting, but that’s a highly speculative rationale for public funding.

Less questionably, more art and more exposure to the arts does enrich society in ways that have nothing to do with external benefits. Culture and arts are by-products of normal social interactions between private individuals. The benefits of art exposure (and art education) are largely accrued privately. When artistic knowledge is shared to nourish or broaden one’s network, the benefits flow from private social interactions that arise naturally, rather than as a consequence of phantom external benefits.

Public Funding and Agitprop

The selection of recipients and projects for government grants or subsidies is especially prone to influence by entrenched political interests. That is indeed the case when it comes to federal agencies that offer grants for the arts.

The same danger looms when government provides a venue or manages aspects of a presentation of art, including curation of content. It’s an avenue through which art can become politicized. The problem, however, is not so much that a particular work might have political implications. As Samuel Andreyev, a Canadian composer says:

“Like any other subject, it is possible for political subjects to be handled sensitively by an artist, provided there is a strong enough element of abstraction and symbolism so that the work does not become merely journalistic.”

Andreyev makes a good point, but government funding and direction can create incentives to politicize art, encouraging more blatant expressions of political viewpoints at the expense of taxpayers.

I’ve certainly admired art despite subtle political implications with which I differed. One can hardly imagine a treatment of the human condition that would not invite tangential political commentary. Still, politicization of art should always be left as a private exercise, not one over which the government of a free society wields influence.

Do Markets Undervalue Art?

What about the artists themselves? The premise that artists deserve subsidies relies on the questionable presumption that the value of their work exceeds its commercial or market value. Thus, taxpayers are asked to pay handsomely for art that is not valued as highly by private buyers.

Artists who benefit from government arts funding are often well established professionally. Less fortunate artists scrape by, finding what market they can while working side gigs. In fact, many less celebrated artists work at their craft on a part-time basis while earning most of their income from day jobs. Should the government support these artists, or artists having few opportunities to promote their work?

It’s not clear that public funding should override the private market’s basis of valuation for established or unestablished artists. However, some government funding finds its way into less celebrated corners of the art world. This report uses data at the census tract level to show that arts organizations located in low income tracts, while receiving less, still get a disproportionate share of federal grant dollars relative to their share of the population. This finding should be viewed cautiously, as data at this level of aggregation has limitations. The findings do not imply that “starving artists” receive a disproportionate share of those dollars. Nor do they prove that federal grants benefit low-income individuals disproportionately via improved access to the arts. Again, the findings are based on the location of organizations. And again, large organizations receive the bulk of these grants.

Drawing the Line

So where do we draw the line on taxpayer subsidies for the arts? The standard, public-goods justification is false. While externalities may exist, they are not always positive, and it is hardly the state’s proper role to fund art that “challenges” notions about good and bad art. In that vein, just as law tends to be ineffective when it lacks consensus, public arts funding breeds dissent when the art is controversial.

The legitimacy of public arts funding ultimately depends on whether the art itself has a true public purpose. To varying degrees, this might include the architecture and interior design of public buildings, landscaping of parks, as well as certain monuments and statuary. Even within these disciplines, the selection of form, content, and the artists who will execute the work can be controversial. That might be unavoidable, though controversy will be minimized when the content of publicly-funded art remains within cultural norms.

Beyond those limited purposes, funding art at the federal level is difficult to justify. That role simply does not fall within the constitutionally-enumerated powers of the federal government. The tenuous rationale for subsidies implies that art is undervalued, despite the existence of a vibrant private ecosystem for art, including private support foundations and markets. To the extent that public subsidies line the pockets of elites or support art that would otherwise fail a market test, they represent a wasteful misallocation of resources.

Funding art might seem less troublesome at lower levels of government, where elected representatives and policymakers are in more intimate contact with voters and taxpayers. Still, the same economic reservations apply. At local levels, institutions like community orchestras and concerts series might be broadly supported. Publicly-funded museums, theatrical venues, and other facilities might be accepted by voters as well. If parents have educational choices and expect schools to teach art, it should be funded at public schools, so long as the content stays within cultural norms and is age-appropriate. Of course, all of these matters are up to local voters.

The greatest danger of public funding for the arts is that it tends to be utilized as a tool of political propaganda. Having the state select winners and losers in the arts invites politicization, undermining freedom and our system of government. On that point, Thomas Jefferson once made this observation:

“To compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagations of opinions which he disbelieves and abhors, is sinful and tyrannical.“