Tags

CARES Act, Covid-19, Delta Variant, Don Wolt, False Positives, Health and Human Services, HHS Protect, Jennifer Rubin, Monica Gandhi, Omicron Variant, PCR Test, Pediatric COVID, Phil Kerpen, Positivity Rate

That’s our Commander and Chief this week, posing in a mask on the beach in what is a phenomenal display of stupidity. More importantly, that kind of messaging contributes to the wholly unwarranted panic surrounding the Omicron variant of Covid-19. Panic, you say? Take a look at this admission from a New York health official. She says a recent alert on pediatric hospitalizations was driven by a desire to “motivate” parents to vaccinate their children. Yet Covid has never posed a significant risk to children. And take a look at what this insane physician posted. It’s fair to say he’s “catastrophizing”, an all too common psychological coping mechanism for alarmists.

The Omicrommon Cold

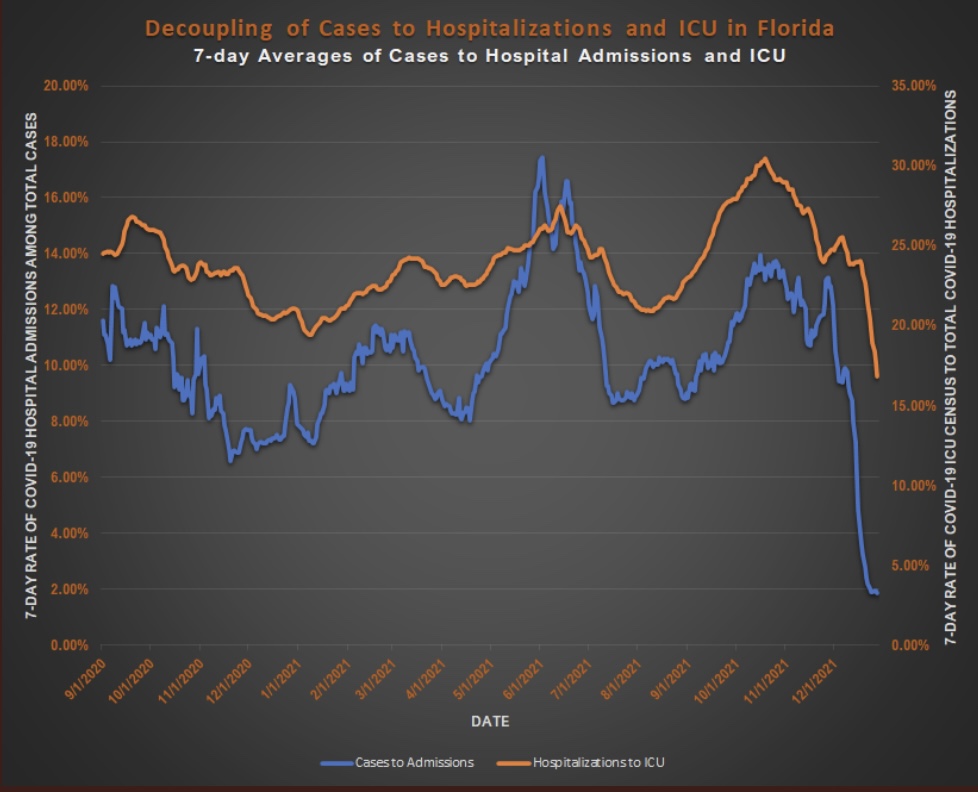

Given Omicron’s low apparent severity, it might be the variant that allows a return to normalcy. It’s perhaps the forefront of a more benign but endemic Covid, as it seems to be out-competing and displacing the far more dangerous Delta variant. In fact, Omicron infections are protective against Delta, probably for much longer than vaccines. The mild severity we’ve seen thus far is due in part to protection from vaccines and acquired immunity against breakthrough infections, but there’s more: there are plenty of non-breakthrough cases of Omicron, and most hospitalizations are among the unvaccinated. Yet we see this drastic decline in Florida’s ratio of ICU to hospital admissions (as well as a reduction in length of stay — not shown on chart). Similar patterns appear elsewhere. Omicron’s more rapid onset and course make it less likely that these patterns are caused by lags in the data.

Panic Begets Lockdowns

The frantic Omicron lunacy is driven partly by data on the number of new cases, which can be highly misleading as a guide to the real state of affairs. Testing is obviously necessary for diagnosis, but case totals as an emphasis of reporting have a way of feeding back to panic and destructive public policy: every wave brings surges in cases and the positivity rate prompting authoritarian measures with dubious benefits and significant harms (see here and here).

Flawed Case Data

In many respects, the data on Covid case totals have been flawed from the beginning, owing largely to regulators. At the outset in early 2020, there was a severe shortage in testing capacity due to the CDC’s delays in approving tests, as well as restrictions on testing by private labs. Many cases went undiagnosed, including a great many asymptomatic cases. The undercount of cases inflated the early case fatality rate (CFR). Subsequently, the FDA dithered in its reviews of low-cost, rapid, at-home tests. The latest revelation was the Administration’s decision in October to nix a large rollout of at-home tests. While the results of those tests are often unreported, they would have been helpful to individual decisions about seeking care and quarantining.

The PCR test finally distributed in March 2020 was often too sensitive, which the CDC has finally acknowledged, This is a flaw I’ve noted several times in the past. It led to false positives. Hospitals began testing all admitted patients, which was practical, and the hospitals were happy to do so given the financial rewards attendant to treating Covid patients under the CARES Act. However, it resulted in the counting of “incidental” Covid-positives: patients admitted with Covid, but not for Covid. That inflates apparent severity gleaned through measures like hospitalized cases, and it can distort counts of Covid fatalities and the CFR.

On balance, the bias caused by the test shortage at the start of the pandemic likely constrained total case counts, but the subsequent impact of testing practices is uncertain except for incidental hospitalized cases and the impact on counts of deaths.

Omicron Enlightenment

Omicron spreads rapidly, so the clamoring for tests by panicked consumers has resulted in another testing shortage, both for PCR tests and at-home tests at pharmacies. The shortage might not be relieved until the Omicron wave has crested, which could occur within a matter of a few weeks if the experience of South Africa and London are guides. In the meantime, another deleterious effect of the “case panic” is the crush of nervous individuals at emergency rooms presenting with relatively minor symptoms. Now more than ever, many of the cases identified at hospitals are incidental, particularly pediatric cases.

A thread by Monica Gandhi, and her recent article in the New York Times, makes the case that hospitalizations should be the primary focus of Covid reporting, rather than new cases. Quite apart from the inaccuracies of case counting and the mild symptoms experienced by most of those infected, Gandhi reasons that breakthrough infections so common with Omicron render case counts less relevant. That’s because high rates of vaccination (not to mention natural immunity from prior infections) reduce severity. Even Jennifer Rubin has taken this position, a complete reversal of her earlier case-count sanctimony.

Incidental Infections

Phil Kerpen’s reaction to Gandhi’s article was on point, however:

“Unless HHS Protect adds a primary [diagnosis] column, hospital census isn’t much more useful than cases.”

HHS Protect refers to the Health and Human Services public data hub. Without knowing whether Covid is the primary diagnosis at admission, we have no way of knowing whether the case is incidental. If Covid is the primary reason for admission, the infection is likely to be fairly severe. It is more useful to know both the number of patients hospitalized for Covid and tge number hospitalized for other conditions (incidentally with Covid). The distinction has been extremely important to those interpreting data from South Africa, where a high proportion of incidental admissions was a tip-off that Omicron is less severe than earlier variants.

The absence of such coding is similar to the confusion caused by the CDC’s decision early in pandemic to issue new guidance on the completion of death certificates when Covid is present or even suspected. A special exception was created at that time requiring all deaths involving primary or incidental Covid infections to be ruled as Covid deaths. This represented another terrible corruption of the data.

Summary

Earlier variants of Covid were extremely dangerous to the elderly, obese, and the immune-compromised. Yet public health authorities seemed to take every opportunity to mismanage the pandemic, including contradictory messaging and decisions that compromised the usefulness of data on the pandemic. But here we are with Omicron, which might well be the variant that spells the end of the deadly Covid waves, and the focus is still squarely on case counts, vaccine mandates, useless masking requirements, and President Brandon wearing a mask on the beach!

Case counts should certainly be available, as Gandhi goes to great lengths to emphasize. However, other metrics like hospitalizations are more reliable indicators of the current wave’s severity, especially if paired with information on primary diagnoses. Fortunately, there has been a very recent shift of interest to that kind of focus because the superior information content of reports from countries like South Africa and Denmark is too obvious. As Don Wolt marvels:

“Behold the sudden interest by the public health establishment in the “With/From” COVID distinction. While long an important & troubling issue for many who sought to understand the true impact of the virus, it was, until very recently, actively ignored by Fauci & crew.”

That change in emphasis would reduce the current sense of panic, partly by making it more difficult for the media to purvey scare stories and for authorities to justify draconian non-pharmaceutical interventions. It’s no exaggeration to say that anything that might keep the authoritarians at bay should be a public health priority.